INTRODUCTION

Inadequate pain management of patients in the emergency departments (EDs) is common.[1] Previous studies indicated that 74% of ED patients were discharged with moderate to severe pain,[2] while 57% of patients did not achieve adequate pain management.[3] Since 2012, effective pain management in the ED has become an important aspect of patient care as oligoanalgesia is the major source of patients’ dissatisfaction,[4,5] which also affects financial reimbursement for EDs.[6]

Oligoanalgesia in the ED had been associated with concerns for drug-seeking behavior[1] and providers’ perception that pain was exacerbated.[7] A previous study also reported that emergency providers (EPs) did not provide adequate pain medication, even in patients with objective findings requiring surgical evaluation.[8] However, Tran et al’s study[8] was limited by a small sample size and a heterogeneous group of surgical pathologies (neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, vascular emergencies, etc.). Furthermore, Tran et al’s study[8] showed that increased doses of opioids did not adequately reduce pain among surgical patients presenting with severe pain.

We hypothesized that there are other factors, besides the amount of pain medication, that might be associated with oligoanalgesia in ED patients with surgical pathologies and moderate to severe pain. Our study aims to identify clinical and laboratory factors, in addition to providers’ interventions in EDs, that are associated with refractory pain among a group of patients who are admitted to an emergency general surgery (EGS) for evaluation and management.

METHODS

Patient selection

We performed a retrospective study of adult patients who were admitted to any inpatient unit under the care of EGS service at an academic tertiary center for surgical evaluation and management. We included patients who were admitted to EGS as the primary admitting service between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016. The study was approved by our institution review board.

We first obtained the list of patients from ExpressCare, the department that manages transfers from other hospitals to our institution. Patients were then matched to our electronic medical record system to obtain further clinical information. Patients were included if their triage pain levels were moderate or severe, which was defined as triage pain score 4-6 for moderate and 7-10 for severe pain. Pain levels were recorded by the numeric rating scale (NRS) 0-10.[11,12] We excluded patients: (1) who were not accompanied by sufficient records from referring EDs; (2) who refused pain medication; (3) who were intubated; (4) whose records were missing pain assessments at triage or departure; (5) who were not transferred directly from an ED; (6) who had triage pain 0-3. We also excluded patients who presented first to our ED to avoid selection bias. According to our institutional practice, when patients are admitted to EGS service and boarding in our ED, they are managed by a resident of the EGS team and not emergency medicine providers. ED nurses will contact EGS residents directly for orders and questions. Thus, most of these patients’ management may not reflect the management of ED providers. Furthermore, these patients would have early EGS consultation and intervention, thus having different outcomes compared with other transferred patients.[13]

Outcome

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients who had pain reduction <2 units on the NRS scale between ED triage and departure. Pain reduction ≥2 units was considered satisfactory by ED patients in previous studies.[11,12] Patients whose pain reduction <2 units on the NRS were considered having refractory pain.

Data collection

Investigators were first trained by the principal investigator for data extractions. Data were extracted to a standardized Microsoft Access form (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington DC, USA), and 10% were randomly reviewed by another investigator (WG) to maintain interrater agreement of at least 90%. Furthermore, to reduce bias, investigators, who were blinded to study hypothesis, extracted data in sections, such that investigators responsible for pain data were not aware of EPs’ therapeutic interventions or laboratory values. The team met every other month to adjudicate data disagreements until data collection was completed.

We extracted our independent variables from referring EDs’ records of eligible patients. Extracted data included demographic factors (age, gender, weight, past medical history, and ED diagnoses), triage, and departure pain scores. We also collected ED laboratory components for the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores: creatinine, platelet level, total bilirubin in addition to serum white blood cell (WBC) counts and lactate level. If a laboratory value was missing from ED record, we substituted it with the admission value upon arrival at our academic medical center. If a value was missing both at ED and admission at the inpatient unit, we imputed the value as 1. We also extracted ED pharmacotherapeutic interventions such as the total amount of pain medication, the volume of intravenous (IV) crystalloids, names of antibiotics, and anti-emetics administered. We only extracted interventions that were documented, either by ED nursing staff, transport teams, or accepting units’ nurses, as administered to the patients during their stay in the EDs prior to transfer.

To evaluate opioid doses, we converted different oral (PO) or IV opioids to morphine equivalent unit (MEU) as previously described.[14] We considered 5 mg of PO oxycodone, hydrocodone as 2 MEUs, while 0.15 mg of IV hydromorphone or 0.01 mg of IV fentanyl was equivalent to 1 MEU.

Data analysis

We first used descriptive data to describe the characteristics of patients with satisfactory pain reduction or refractory pain. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range as appropriate. These continuous data were compared using the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test when appropriate. Categorical data were compared by the Chi-square test with Yates’ correction.

We performed multivariable logistic regressions to assess effects of independent variables on refractory pain. To identify relevant factors for our multivariable logistic regression, we evaluated each independent variable by univariate logistic regressions. We subsequently included only variables with good association with refractory pain (P-value ≤0.10) in the multivariable logistic regression, in addition to a priori-determined clinically significant factors (MEU per kg of body weight; opioid+non-opioid; IV fluid per kg of body weight). Goodness-of-fit of our regression was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test with P-value >0.05 being considered a good fit. We performed statistical analyses using Minitab version 18 (Limited Liability Company, State College, Pennsylvania, USA). All two-tailed P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

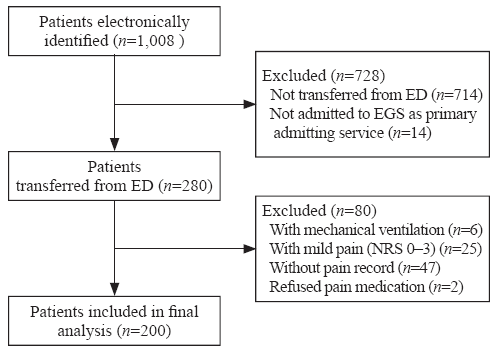

We analyzed the charts of 200 patients who were transferred from different EDs to the EGS service at our academic tertiary center (Figure 1). There were 142 (71%) patients with no refractory pain and 58 (29%) patients with refractory pain. The majority of patients were transferred from EDs for evaluation and management of bowel obstruction (20%, 40/200) and bowel perforation (15%, 30/200). While 35% (70/200) of patients did not undergo any surgical operation, 31% (61/200) of patients underwent laparotomy, and 13% (26/200) of patients had laparoscopic surgery during their hospitalization (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Patient selection diagram. ED: emergency department; EGS: emergency general surgery; NRS: numerating rate scale.

Table 1 Characteristics of ED patients who were admitted to EGS for evaluation and management

| Parameters | All patients |

|---|---|

| Total patients, n (%) | 200 (100) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 88 (44) |

| Female | 112 (56) |

| Age in years, mean±SD | 55±19 |

| Past medical history, n (%) | |

| CHF | 13 (7) |

| Hypertension | 95 (48) |

| DM | 36 (18) |

| Any liver disease | 13 (7) |

| Any kidney disease | 12 (6) |

| ESI, median (IQR) | 3 (2-3) |

| Triage systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean±SD | 133±20 |

| Triage heart rate (bpm), mean±SD | 94±19 |

| Triage pain score, mean±SD | 8±2 |

| Triage GCS, median (IQR) | 15 (14-15) |

| ED LOS (minutes), median (IQR) | 491 ( 327-728) |

| Pain score at departure, mean±SD | 5±3 |

| Total MEU, mean±SD | 12±11 |

| Total IVF (liter), mean±SD | 1.4±1.0 |

| Refractory pain at ED departure, n (%) | 58 (29) |

| ED diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Appendicitis | 4 (2) |

| Bowel obstruction | 40 (20) |

| Bowel perforation | 30 (15) |

| Bowel ischemia | 16 (8) |

| GI bleeding | 12 (6) |

| Hernia | 13 (7) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 28 (14) |

| Pancreatitis | 18 (9) |

| Other | 39 (20) |

| Operation, n (%) | |

| None | 70 (35) |

| Laparotomy | 61 (31) |

| Laparoscopy | 26 (13) |

| Endoscopy | 10 (5) |

| Percutaneous intervention by IR | 9 (4) |

| Incision and drainage | 9 (4) |

| Other | 15 (8) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 8 (4) |

| Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 6 (3-10) |

ED: emergency department; EGS: emergency general surgery; SD: standard deviation; CHF: congestive heart failure; DM: diabetes; ESI: Emergency Severity Index; IQR: interquartile range; bpm: beats per minute; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; LOS: length of stay; MEU: morphine equivalent unit; IVF: intravenous fluid; GI: gastrointestinal; IR: interventional radiology; 1 mmHg=0.133 kPa.

Patients’ clinical factors

Overall, patients with refractory pain had significantly higher SOFA score compared with those with no refractory pain. Patients with refractory pain also had significantly higher serum levels of WBC and lactate. Patients with refractory pain had higher pain score at ED departure and a lower rate of pain score change, as compared with patients with no refractory pain. Patients with refractory pain at ED departure also had higher mortality and longer hospital length of stay, as compared with patients with no refractory pain (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of clinical factors between patients with and without refractory pain

| Parameters | All (n=200) | No refractory pain (group A) (n=142) | Refractory pain (group B) (n=58) | P-value (A vs. B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOFA score, mean±SD | 2±1 | 2±1 | 3±2 | 0.001 |

| Shock index, mean±SD | 0.86±0.30 | 0.80±0.30 | 0.95±0.40 | 0.030 |

| WBC (×109/L), mean±SD | 13±7 | 13±7 | 15±8 | 0.034 |

| Lactate (mg/dL), mean±SD | 1.9±1.8 | 1.4±0.9 | 3.4±2.0 | 0.001 |

| Triage GCS, median (IQR) | 15 (14-15) | 15 (14-15) | 15 (14-15) | 0.510 |

| Triage pain score, mean±SD | 8±2 | 8±2 | 8±1 | 0.400 |

| Triage SBP (mmHg), mean±SD | 133±20 | 135±27 | 127±32 | 0.070 |

| Triage heart rate (beats per minute), mean±SD | 94±19 | 93±18 | 97±23 | 0.220 |

| Pain score at ED departure, mean±SD | 5±3 | 4±3 | 8±2 | 0.001 |

| Change of pain score, mean±SD | -3±3 | -5±2 | 0±1 | 0.001 |

| ED length of stay (minutes), median (IQR) | 491 (327-728) | 524 (359-774) | 355 (233-570) | 0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 8 (4) | 3 (2) | 5 (9) | 0.047 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) | 6 (3-10) | 6 (3-9) | 9 (4-15) | 0.002 |

SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SD: standard deviation; WBC: white blood cell; bpm: beats per minute; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; IQR: interquartile range; SBP: systolic blood pressure; ED: emergency department.

Interventions in the EDs

Patients with refractory pain received less frequent pain medication administration (3 [3-5]) than patients with no refractory pain (4 [3-7], P=0.001) (Table 3). There were also a higher percentage of patients with refractory pain who did not receive any pain medication when compared with those with no refractory pain (Table 3). Furthermore, patients with refractory pain received less MEU per kg of body weight, when compared with patients with no refractory pain (Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison of ED interventions for patients with and without refractory pain

| Parameters | All (n=200) | No refractory pain (group A) (n=142) | Refractory pain (group B) (n=58) | P-value (A vs. B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of pain medication administration, median (IQR) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-7) | 3 (3-5) | 0.001 |

| Pain medication type, n (%)* | ||||

| No pain medication | 26 (13) | 13 (9) | 13 (22) | 0.020 |

| Any opioids | 164 (82) | 123 (87) | 41 (70) | 0.010 |

| Opioids+non-opioids | 20 (10) | 14 (10) | 6 (10) | 0.890 |

| Non-opioids | 30 (15) | 20 (14) | 10 (17) | 0.730 |

| Total MEU, mean±SD | 22±11 | 13±9 | 9±16 | 0.020 |

| MEU per kg (body weight), mean±SD | 0.15±0.16 | 0.18±0.20 | 0.11±0.10 | 0.004 |

| Total intravenous crystalloids (liter), mean±SD | 1.4±1.0 | 1.2±0.9 | 1.8±1.2 | 0.017 |

| IVF per kg, mean±SD | 17±1 | 16±14 | 21±17 | 0.060 |

| Any anti-emetics, n (%) | 134 (67) | 97 (68) | 37 (64) | 0.650 |

| Total number of antibiotics, median (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-2) | 0.038 |

| Receiving any antibiotics, n (%) | 92 (46) | 60 (42) | 32 (55) | 0.130 |

ED: emergency department; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; *: one patient may have more than one category; MEU: morphine equivalent unit; IVF: intravenous fluid.

Clinical factors associated with refractory pain at ED departure

Multivariable logistic regression, which only included relevant clinical factors as determined by univariate logistic regression, showed that each mg/dL increment of serum lactate was associated with 3.8 times higher odds that EGS patients had refractory pain when they left the referring EDs (Table 4). Furthermore, each pain medication administration in the ED was also associated with 20% less likelihood that patients had refractory pain at ED departure (odds ratio [OR] 0.80, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.68-0.98, P=0.02).

Table 4 Results from multivariable logistic regression to assess clinical factors and refractory pain among patients admitted to emergency general surgery from emergency departments

| Independent variables | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Serum lactate | 4.60 | 2.80-7.60 | 0.001 | 3.80 | 2.10-6.80 | 0.001 |

| Number of pain medication administration | 0.84 | 0.75-0.95 | 0.001 | 0.80 | 0.68-0.98 | 0.020 |

| Gender - male | 2.30 | 1.20-4.40 | 0.008 | 1.80 | 0.65-5.20 | 0.250 |

| Past medical history - any kidney disease | 2.30 | 1.20-4.30 | 0.080 | 1.90 | 0.40-9.10 | 0.430 |

| Emergency Severity Index | 0.55 | 0.30-0.97 | 0.040 | 0.60 | 0.20-1.90 | 0.420 |

| SOFA | 1.40 | 1.20-1.70 | 0.001 | 1.10 | 0.80-1.50 | 0.570 |

| Triage SBP | 0.98 | 0.98-1.00 | 0.047 | 1.01 | 0.98-1.03 | 0.350 |

| WBC | 1.04 | 1.00-1.08 | 0.033 | 0.90 | 0.90-1.04 | 0.350 |

| MEU per kg (body weight)* | 0.05 | 0.00-0.60 | 0.007 | 0.10 | 0.01-1.50 | 0.380 |

| Opioids+non-opioids* | 1.30 | 0.50-3.70 | 0.590 | 1.60 | 0.40-6.30 | 0.490 |

| IVF per kg (body weight)* | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.044 | 0.98 | 0.90-1.02 | 0.460 |

| Number of antibiotics | 1.50 | 1.03-2.10 | 0.032 | 1.60 | 0.90-2.80 | 0.090 |

| Diagnosis - bowel obstruction | 0.40 | 0.10-0.90 | 0.022 | 0.80 | 0.20-2.80 | 0.690 |

| Diagnosis - bowel perforation | 2.10 | 0.90-5.00 | 0.087 | 0.60 | 0.10-2.90 | 0.530 |

Independent variables with P-value ≤0.10 in univariable logistic regression, in addition to a priori-determined clinically significant factors, were included in the multivariable logistic regression; CI: confidence interval; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SBP: systolic blood pressure; WBC: white blood cell; MEU: morphine equivalent unit; IVF: intravenous fluid; *: clinically significant factors.

DISCUSSION

Our study of patients with moderate to severe pain and transferred to an EGS service for further management showed that almost 30% of patients had refractory pain. Furthermore, only serum lactate and the total number of pain medication administrations were identified as two clinical factors that were significantly associated with refractory pain at ED departure.

Oligoanalgesia in the ED settings has been described in previous studies.[2,3] There had been multiple studies suggesting the underlying causes of ED oligoanalgesia. Miner et al[7] reported that up to 32% of physicians perceived that African American patients exaggerated their pain symptoms by greater than 15 mm on a visual analog scale of 100 mm. Furthermore, providers also hesitated to provide pain medication for concerns of drug-seeking, especially during the current opioid crisis. Providers tended to mistrust patients who reported severe pain in condition related to IV drug abuse[1] (soft tissue infection), which was shown to have high percentages of oligoanalgesia, compared with other pathologies.[8] Furthermore, ED providers tended not to give pain medication to patients with possible surgical abdomen until patients were evaluated by surgeons.[15] Similar to previous studies which suggested provider-related reasons for oligoanalgesia in ED,[1,2,7,15] our study showed that a provider-related intervention (the number of pain medication administration) was associated with refractory pain. However, our study was able to provide an objective cause (serum lactate level) that may have been associated with refractory in ED patients with surgical pathologies. The findings of our study, if confirmed by further studies, will provide an objective measurement for ED providers to assess patients with refractory pain from surgical pathologies.

The mechanism that hyperlactatemia was associated with pain in patients has been unclear. Increased serum lactate level is caused by tissue hypoxia resulting in anaerobic glycolysis[16] and inflammatory responses.[17] In animal studies, weak acids such as lactic acid activated acid-sensing ion channels responsible for nociception and increased pain.[17,18,19] It was probable that EGS patients, who had refractory pain in our study, developed hyperlactatemia because of their systemic inflammatory responses, as evidenced by their higher shock index and SOFA score. Increased serum lactate levels additionally caused higher, longer-lasting pain due to activated nociception receptors. Further studies are needed to confirm our observation and to investigate whether lactate clearance also improves pain in patients with objective findings responsible for pain as in EGS patients.

A previous study reported that emergency providers did not adequately treat patients who were transferred for surgical evaluations[8] as patients were given a median of 0.09 mg/kg MEU, which was less than the recommended dose of 0.10 mg/kg of MEU.[20] However, our study showed that emergency providers adequately treated these patients who were transferred to an EGS service for further management. Patients with refractory pain in our study received the recommended dose of 0.10 mg/kg of MEU, although this 0.10 mg/kg could also be inadequate[20] in patients with severe pain. Furthermore, patients with refractory pain had shorter ED length of stay, which may have been associated with a lower frequency of pain medication administration. As a result, it was likely that refractory pain in patients with surgical pathologies for EGS as in our study, was caused by patient’s disease severity, which resulted in hyperlactatemia and faster transfer to higher level care, but not from emergency providers’ inadequate interventions.

Limitations

Our study has many limitations. First, the exclusion of patients who presented first to our institution ED may limit our study’s generalizability as our patient population only consisted of patients who were transferred from other hospitals’ EDs. We could not assess serum lactate clearance as a marker for refractory pain. Almost all patients did not have a repeat lactate level in the EDs, and many patients whose lactate levels were less than 2.0 mg/dL did not have a repeat lactate level upon admission at our quaternary academic center. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we could not explain the practice variation between emergency providers’ clinical care for these patients. We also did not use mortality and hospital length of stay between patients with refractory pain and with no refractory pain as outcomes in any regression analyses because patient’s mortality and length of stay depended on multiple in-hospital factors, besides ED management. Most of these factors would not be available to emergency providers, and would not affect their management of patients prior to transfer.

CONCLUSIONS

Among ED patients with objective surgical pathologies and moderate or severe pain, serum lactate levels were associated with an increased likelihood of refractory pain, despite adequate pain control by emergency providers. Future studies involving pain control in patients with elevated serum lactate are needed.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the investigation and the development of this manuscript.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by our institution review board.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributors: WG, BB, QKT: concept and study design; WG, JFB, BC, JM, TN, JP, MR, ST: data acquisition, data quality, and analysis. All authors participated in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Reference

Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine

URL PMID:15039693 [Cited within: 4]

Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study

DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.005

URL

PMID:17306626

[Cited within: 3]

UNLABELLED: Pain is the most common reason for emergency department (ED) use, and oligoanalgesia in this setting is known to be common. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has revised standards for pain management; however, the impact of these regulatory changes on ED pain management practice is unknown. This prospective, multicenter study assessed the current state of ED pain management practice. After informed consent, patients aged 8 years and older with presenting pain intensity scores of 4 or greater on an 11-point numerical rating scale completed structured interviews, and their medical records were abstracted. Eight hundred forty-two patients at 20 US and Canadian hospitals participated. On arrival, pain intensity was severe (median, 8/10). Pain assessments were noted in 83% of cases; however, reassessments were uncommon. Only 60% of patients received analgesics that were administered after lengthy delays (median, 90 minutes; range, 0 to 962 minutes), and 74% of patients were discharged in moderate to severe pain. Of patients not receiving analgesics, 42% desired them; however, only 31% of these patients voiced such requests. We conclude that ED pain intensity is high, analgesics are underutilized, and delays to treatment are common. Despite efforts to improve pain management practice, oligoanalgesia remains a problem for emergency medicine. PERSPECTIVE: Despite the frequency of pain in the emergency department, few studies have examined this phenomenon. This study documents high pain intensity and suboptimal pain management practices in a large multicenter ED network in the United States and Canada. These findings suggest that there is much room for improvement in this area.

Outcomes after intravenous opioids in emergency patients: a prospective cohort analysis

DOI:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00405.x

URL

PMID:19426295

[Cited within: 2]

OBJECTIVES: Pain management continues to be suboptimal in emergency departments (EDs). Several studies have documented failures in the processes of care, such as whether opioid analgesics were given. The objectives of this study were to measure the outcomes following administration of intravenous (IV) opioids and to identify clinical factors that may predict poor analgesic outcomes in these patients. METHODS: In this prospective cohort study, emergency patients were enrolled if they were prescribed IV morphine or hydromorphone (the most commonly used IV opioids in the study hospital) as their initial analgesic. Patients were surveyed at the time of opioid administration and 1 to 2 hours after the initial opioid dosage. They scored their pain using a verbal 0-10 pain scale. The following binary analgesic variables were primarily used to identify patients with poor analgesic outcomes: 1) a pain score reduction of less than 50%, 2) a postanalgesic pain score of 7 or greater (using the 0-10 numeric rating scale), and 3) the development of opioid-related side effects. Logistic regression analyses were used to study the effects of demographic, clinical, and treatment covariates on the outcome variables. RESULTS: A total of 2,414 were approached for enrollment, of whom 1,312 were ineligible (658 were identified more than 2 hours after IV opioid was administered and 341 received another analgesic before or with the IV opioid) and 369 declined to consent. A total of 691 patients with a median baseline pain score of 9 were included in the final analyses. Following treatment, 57% of the cohort failed to achieve a 50% pain score reduction, 36% had a pain score of 7 or greater, 48% wanted additional analgesics, and 23% developed opioid-related side effects. In the logistic regression analyses, the factors associated with poor analgesia (both <50% pain score reduction and postanalgesic pain score of >or=7) were the use of long-acting opioids at home, administration of additional analgesics, provider concern for drug-seeking behavior, and older age. An initial pain score of 10 was also strongly associated with a postanalgesic pain score of >or=7. African American patients who were not taking opioids at home were less likely to achieve a 50% pain score reduction than other patients, despite receiving similar initial and total equianalgesic dosages. None of the variables we assessed were significantly associated with the development of opioid-related side effects. CONCLUSIONS: Poor analgesic outcomes were common in this cohort of ED patients prescribed IV opioids. Patients taking long-acting opioids, those thought to be drug-seeking, older patients, those with an initial pain score of 10, and possibly African American patients are at especially high risk of poor analgesia following IV opioid administration.

The efficacy and safety of pain management before and after implementation of hospital-wide pain management standards: is patient safety compromised by treatment based solely on numerical pain ratings?

DOI:10.1213/01.ANE.0000155970.45321.A8

URL

PMID:16037164

[Cited within: 1]

UNLABELLED: Inadequate analgesia in hospitalized patients prompted the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations in 2001 to introduce standards that require pain assessment and treatment. In response, many institutions implemented treatment guided by patient reports of pain intensity indexed with a numerical scale. Patient safety associated with treatment of pain guided by a numerical pain treatment algorithm (NPTA) has not been examined. We reviewed patient satisfaction with pain control and opioid-related adverse drug reactions before and after implementation of our NPTA. Patient satisfaction with pain management, measured on a 1-5 scale, significantly improved from 4.13 to 4.38 (P < 0.001) after implementation of an NPTA. The incidence of opioid over sedation adverse drug reactions per 100,000 inpatient hospital days increased from 11.0 pre-NPTA to 24.5 post-NPTA (P < 0.001). Of these patients, 94% had a documented decrease in their level of consciousness preceding the event. Although there was an improvement in patient satisfaction, we experienced a more than two-fold increase in the incidence of opioid over sedation adverse drug reactions in our hospital after the implementation of NPTA. Most adverse drug reactions were preceded by a documented decrease in the patient's level of consciousness, which emphasizes the importance of clinical assessment in managing pain. IMPLICATIONS: Although patient satisfaction with pain management has significantly improved since the adoption of pain management standards, adverse drug reactions have more than doubled. For the treatment of pain to be safe and effective, we must consider more than just a one-dimensional numerical assessment of pain.

Patients’ perceptions of quality of care at an emergency department and identification of areas for quality improvement

URL PMID:16879549 [Cited within: 1]

Value-based purchasing: what’s the score? Reward or penalty, step up to the plate

URL PMID:23571763 [Cited within: 1]

Patient and physician perceptions as risk factors for oligoanalgesia: a prospective observational study of the relief of pain in the emergency department

DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2005.08.008

URL

PMID:16436793

[Cited within: 3]

OBJECTIVES: Previous studies have reported that pain is undertreated in the emergency department (ED), but few physician-dependent risk factors have been identified. In this study, the authors determine whether pain treatment and relief in ED patients are negatively associated with the physician's perception of whether the patient was exaggerating symptoms, and with the patient and physician's perceptions of the interaction between them, as well as whether demographic characteristics were associated with these perceptions. METHODS: This was a prospective observational study of patients who were undergoing treatment for painful disorders in the ED. Before treatment for pain, patients were asked to complete a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) describing their pain. Demographic information and pain treatments administered were recorded. Patients completed a second pain VAS before discharge from the ED. Patients were then asked to complete three queries describing their perception of their interaction with the physician. After the patient had left the department, the patient's physician was asked to complete a query describing his or her perception of the interaction and to complete a VAS describing how likely it was that the patient was exaggerating symptoms to obtain pain medicines for nonmedical purposes. RESULTS: There were 1,695 patients enrolled in the study; 32 patients were excluded because of missing or incomplete data, leaving 1,663 for analysis. Of these patients, 71.9% received a pain medication while in the ED. There was no association between the physician's VAS for perceived exaggeration of symptoms, the queries describing physician-patient interactions, and patient ethnicity and whether patients received pain treatment in the ED. There was a negative correlation between the physician's VAS for perceived exaggeration of symptoms and the change in the patient's pre- and posttreatment pain VAS scores. The physician's VAS score for perceived exaggeration of symptoms was higher among Native American patients than among other ethnic groups (p < or = 0.001). The patient and physician queries rating their interaction show a decreased absolute reduction of VAS pain scores (p > or = 0.001) and a reduction in the number of patients having at least a 50% reduction in their pain VAS score when interactions were rated

Emergency providers’ pain management in patients transferred to intensive care unit for urgent surgical interventions

URL PMID:30202502 [Cited within: 5]

The critical care resuscitation unit transfers more patients from emergency departments faster and is associated with improved outcomes

DOI:10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.09.041

URL

PMID:31761462

BACKGROUND: Transfer delays of critically ill patients from other hospitals' emergency departments (EDs) to an appropriate referral hospital's intensive care unit (ICU) are associated with poor outcomes. OBJECTIVES: We hypothesized that an innovative Critical Care Resuscitation Unit (CCRU) would be associated with improved outcomes by reducing transfer times to a quaternary care center and times to interventions for ED patients with critical illnesses. METHODS: This pre-post analysis compared 3 groups of patients: a CCRU group (patients transferred to the CCRU during its first year [July 2013 to June 2014]), a 2011-Control group (patients transferred to any ICU between July 2011 and June 2012), and a 2013-Control group (patients transferred to other ICUs between July 2013 and June 2014). The primary outcome was time from transfer request to ICU arrival. Secondary outcomes were the interval between ICU arrival to the operating room and in-hospital mortality. RESULTS: We analyzed 1565 patients (644 in the CCRU, 574 in the 2011-Control, and 347 in 2013-Control groups). The median time from transfer request to ICU arrival for CCRU patients was 108 min (interquartile range [IQR] 74-166 min) compared with 158 min (IQR 111-252 min) for the 2011-Control and 185 min (IQR 122-283 min) for the 2013-Control groups (p < 0.01). The median arrival-to-urgent operation for the CCRU group was 220 min (IQR 120-429 min) versus 439 min (IQR 290-645 min) and 356 min (IQR 268-575 min; p < 0.026) for the 2011-Control and 2013-Control groups, respectively. After adjustment with clinical factors, transfer to the CCRU was associated with lower mortality (odds ratio 0.64 [95% confidence interval 0.44-0.93], p = 0.019) in multivariable logistic regression. CONCLUSION: The CCRU, which decreased time from outside ED's transfer request to referral ICU arrival, was associated with lower mortality likelihood. Resuscitation units analogous to the CCRU, which transfer resource-intensive patients from EDs faster, may improve patient outcomes.

Emergency general surgery: defining burden of disease in the State of Maryland

Acute care surgery services continue expanding to provide emergency general surgery (EGS) care. The aim of this study is to define the characteristics of the EGS population in Maryland. Retrospective review of the Health Services Cost Review Commission database from 2009 to 2013 was performed. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma-defined EGS ICD-9 codes were used to define the EGS population. Data collected included patient demographics, admission origin [emergency department (ED) versus non-ED], length of stay (LOS), mortality, and disposition. There were 3,157,646 encounters. In all, 817,942 (26%) were EGS encounters, with 76 per cent admitted via an ED. The median age of ED patients that died was 74 years versus 61 years for those that lived (P < 0.001). Twenty one per cent of ED admitted patients had a LOS > 7 days. Of 78,065 non-ED admitted patients, the median age of those that died was 68 years versus 59 years for those that lived (P < 0.001). Twenty eight per cent of non-ED admits had LOS > 7 days. In both ED and non-ED patients, there was a bimodal distribution of death, with most patients dying at LOS 7 days. In this study, EGS diagnoses are present in 26 per cent of inpatient encounters in Maryland. The EGS population is elderly with prolonged LOS and a bimodal distribution of death.

What decline in pain intensity is meaningful to patients with acute pain?

Simple clinical targets associated with a high level of patient satisfaction with their pain management

URL PMID:21489167 [Cited within: 2]

Interhospital transfer for emergency general surgery: an independent predictor of mortality

DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.055

URL

PMID:30166049

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Emergency general surgery (EGS) admissions account for more than 3 million hospitalizations in the US annually. We aim to better understand characteristics and mortality risk for EGS interhospital transfer patients compared to EGS direct admissions. METHODS: Using the 2002-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample we identified patients aged >/=18 years with an EGS admission. Patient demographics, hospitalization characteristics, rates of operation and mortality were compared between patients with interhospital transfer versus direct admissions. RESULTS: Interhospital transfers comprised 2% of EGS admissions. Interhospital transfers were more likely to be white, male, Medicare insured, and had higher rates of comorbidities. Interhospital transfers underwent more procedures/surgeries and had a higher mortality rate. Mortality remained elevated after controlling for patient characteristics. CONCLUSIONS: Interhospital transfers are at higher risk of mortality and undergo procedures/surgeries more frequently than direct admissions. Identification of contributing factors to this increased mortality may identify opportunities for decreasing mortality rate in EGS transfers.

Opioid conversions in acute care

DOI:10.1345/aph.1H421 URL [Cited within: 1]

Analgesic administration to patients with an acute abdomen: a survey of emergency medicine physicians

Sepsis-associated hyperlactatemia

A TRPA1-dependent mechanism for the pungent sensation of weak acids

DOI:10.1085/jgp.201110615

URL

PMID:21576376

[Cited within: 2]

Acetic acid produces an irritating sensation that can be attributed to activation of nociceptors within the trigeminal ganglion that innervate the nasal or oral cavities. These sensory neurons sense a diverse array of noxious agents in the environment, allowing animals to actively avoid tissue damage. Although receptor mechanisms have been identified for many noxious chemicals, the mechanisms by which animals detect weak acids, such as acetic acid, are less well understood. Weak acids are only partially dissociated at neutral pH and, as such, some can cross the cell membrane, acidifying the cell cytosol. The nociceptor ion channel TRPA1 is activated by CO(2), through gating of the channel by intracellular protons, making it a candidate to more generally mediate sensory responses to weak acids. To test this possibility, we measured responses to weak acids from heterologously expressed TRPA1 channels and trigeminal neurons with patch clamp recording and Ca(2+) microfluorometry. Our results show that heterologously expressed TRPA1 currents can be induced by a series of weak organic acids, including acetic, propionic, formic, and lactic acid, but not by strong acids. Notably, the degree of channel activation was predicted by the degree of intracellular acidification produced by each acid, suggesting that intracellular protons are the proximate stimulus that gates the channel. Responses to weak acids produced a Ca(2+)-independent inactivation that precluded further activation by weak acids or reactive chemicals, whereas preactivation by reactive electrophiles sensitized TRPA1 channels to weak acids. Importantly, responses of trigeminal neurons to weak acids were highly overrepresented in the subpopulation of TRPA1-expressing neurons and were severely reduced in neurons from TRPA1 knockout mice. We conclude that TRPA1 is a general sensor for weak acids that produce intracellular acidification and suggest that it functions within the pain pathway to mediate sensitivity to cellular acidosis.

Serotonin facilitates peripheral pain sensitivity in a manner that depends on the nonproton ligand sensing domain of ASIC3 channel

URL PMID:23467344 [Cited within: 1]

Lactate concentrations in incisions indicate ischemic-like conditions may contribute to postoperative pain

URL PMID:16949881 [Cited within: 1]

Intravenous morphine at 0.1 mg/kg is not effective for controlling severe acute pain in the majority of patients

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.03.010

URL

PMID:16187470

[Cited within: 2]

STUDY OBJECTIVE: The objective was to quantify the analgesic effect of a dose of intravenous morphine, 0.1 mg/kg, to emergency department (ED) patients presenting in acute, severe pain. METHODS: This was a prospective convenience cohort of patients aged 21 to 65 years and presenting to an academic urban ED with acute, severe pain. Patients rated their pain intensity on a validated 11-point verbal numeric rating scale ranging from 0,