Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a major public health problem and poses a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems worldwide.[1-4] The emergency department (ED) serves as the first point of contact with the healthcare system and plays a key role in the management of patients with AF, which accounts for 3%-10% of all hospital admissions.[5]Treatment plans are often discussed and initiated at the ED.

Symptom variety and severity of AF differ tremendously from patient to patient. Some individuals experience little to no symptoms, while others report an impaired quality of life due to their high symptom burden. There are several options for the treatment strategies available for AF. Comparable outcomes can be reached using several strategies and patients’ preferences should be considered and valued in a shared decision-making (SDM) approach. A study has shown that patients may wish to receive more detailed information concerning their disease, which is often underestimated by their treating physicians, while the demand for real treatment decision is much smaller.[6]

AF patients with a potentially higher demand for information and involvement in the treatment decision process at the ED need to be identified. AF symptom severity is used to determine how symptoms affect daily life, and AF burden is used to measure AF frequency, duration, and health-care utilization. The aim of this study is to compare available instruments for assessing symptom severity and burden and to identify the best available tool.

Following a scoping search in MEDLINE (via PubMed), we identified instruments of disease burden and symptoms for AF patients. Instruments were considered if they were published in a peer reviewed journal, had a validation study, and were publicly available as an instrument (German or English version). English scores were translated into German using a linguistic validation methodology recommended by the MAPI Institute.[7]

This translation methods includes the following steps: forward translation, backward translation, review by clinicians, cognitive interviews, proofreading, and report. The already existing German version for the Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale (AFSS) questionnaire was updated in collaboration with the MAPI Research Trust, which is now the official German for Austria version. Rights for usage can be obtained via their online clinical outcome assessment distribution service eProvide (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/atrial-fibrillation-severity-scale). The scores are not presented in this paper for copyright reasons.

This study was carried out at the Department of Emergency Medicine of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, an academic tertiary hospital. Each year, 250 to 650 patients with AF are treated here. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (INFO-AF project, vote no. 1617/2019) and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 04299269).

Patients who had an ongoing episode of AF or atrial flutter (AFL), were aged 18 years or older, provided oral informed consent and had sufficient language skills to understand and complete the questionnaire were included in the study. Patients with hemodynamically unstable AF were not included.

The questionnaires were handed to the patients to be completed during their current stay. It included a structured feedback part on perceived difficulties. The results were compared by a committee of experienced emergency physicians (HD, HH, NS, MP, FC, and SS).

Continuous data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical data are presented as absolute counts and relative frequencies. Scatter plots and bar graphs were used for visual presentation. The Bland-Altman analysis was used to test for agreement between the scoring modalities. Microsoft Excel was used for descriptive and interferential statistics.

Eight instruments were identified. Among these, one instrument (CCS-SAF) was excluded because it was a physician-based score, two instruments (AFQol, AFQLQ) were not applicable because they were only available in languages not spoken by the investigators (Spanish, Japanese), one instrument (AFEQT) was not applied because it is fee-based and one instrument (SCL) was excluded because it has a 4-week recall period, which is not suitable for EDs. Finally, three instruments were included (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of the three applied atrial fibrillation disease severity scores

| Instrument | Abbreviations | Overview | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Toronto - Atrial Fibrillation Severity Scale[8,9] | AFSS | 19 item score; questions about frequency, duration and severity of AF episodes and symptoms | Likert scale, Symptom score 0-35, Burden score 3-30 |

| Atrial Fibrillation Symptom and Burden[10] | AFS-B | AFS for symptoms (8 questions), AFB for disease burden (6 questions) | Modified Likert scale; Symptom score 0-40; Burden score 0-25 |

| Quality of Life in Atrial Fibrillation[11] | QLAF | 22 questions in 7 domains; covers main clinical symptoms | Higher score = lower quality of life |

Subsequently, 30 patients (mean age 73±11 years, 10 females), who matched the eligibility criteria and agreed to complete the questionnaires, were included. Concerning their education, 7% of patients had compulsory schooling, 57% an apprenticeship, 23% a higher school certificate and 13% a university degree. About 10% of patients reported no symptoms, 30% mild symptoms, 33% severe symptoms and 27% disabling symptoms. Some of the symptoms mentioned were chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, tachycardia, fainting or dizziness. Nine patients (30%) had new onset AF.

According to patient feedback and the number of missing values due to item non-response, there was no obvious advantage to any of the scores.

The Quality of Life in Atrial Fibrillation (QLAF) scoring system was not further compared statistically to the other two instruments for following reasons: (1) We could not find official recommendations on the calculation of the score in the available literature. (2) QLAF only focuses on symptoms. However, both domains (disease burden and symptoms) seem to be of importance, meaning the other scores are better qualified for our approach. (3) We found less existing literature on QLAF compared to the AFSS and Atrial Fibrillation Symptom and Burden (AFS-B). (4) QLAF is the score with the most overall items, and therefore needs the longest estimated completion time.

Official guidelines for the AFS-B score recommend using the atrial fibrillation burden (AFB)-strict (sum score of six burden variables) to assess burden classes. We decided on using the AFB-total (sum score of duration plus frequency) because the AFB-strict mostly produced a score of 0 (e.g., if patients did not have an AF episode in the last 3 months), and we had a high number of missing values for the AFB-strict (according to the feedback mostly due to patients having trouble answering the questions).

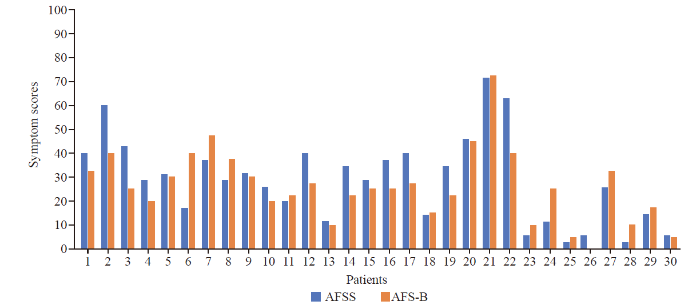

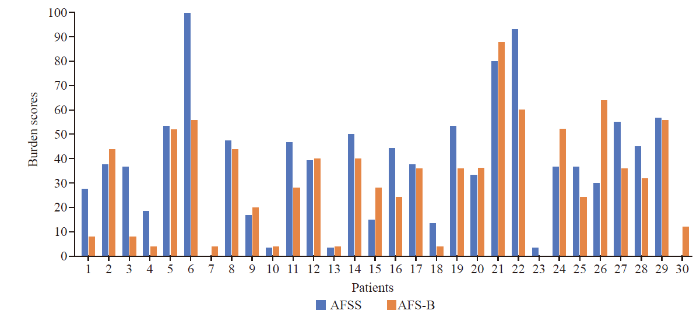

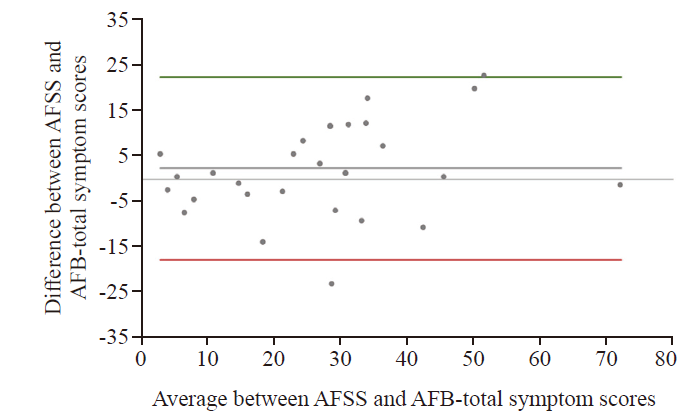

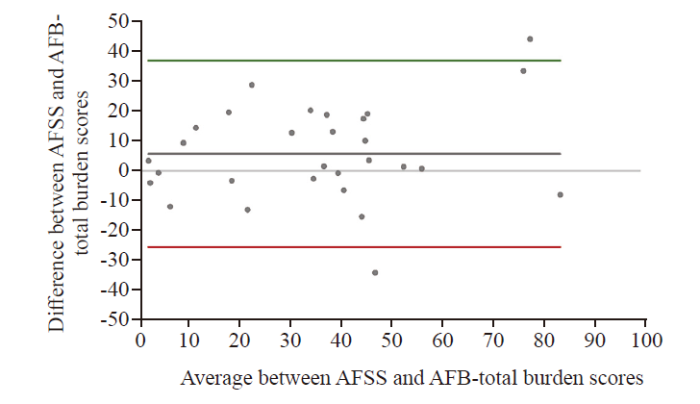

The AFSS and AFB-total symptom scores are displayed in Figure 1, and for AFSS and AFB-total burden scores in Figure 2. The Bland-Altman analysis for AFSS and AFB-total symptom scores showed the bias between AFSS symptom scores and AFS-B symptom scores as 2.49±10.24, with the limits of agreement (LOA) −17.58 to 22.56 (Figure 3). The Bland-Altman analysis for AFSS and AFB-total burden scores showed the bias as 5.64±15.87, with the LOA −25.46 to 36.75 (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

AFSS and AFB-total symptom scores. Values were scaled up to a range of 0-100 for better visualization.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

AFSS and AFB-total burden scores. Values were scaled up to a range of 0-100 for better visualization.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plot for AFSS and AFB-total symptom scores.Values were scaled up to a range of 0-100 for better visualization; middle horizontal line = mean bias; upper and lower horizontal line = limits of agreement.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plot for AFSS and AFB-total burden scores. Values were scaled up to a range of 0-100 for better visualization; middle horizontal line = mean bias; upper and lower horizontal line = limits of agreement.

After the selection process and the qualitative and quantitative assessment of the instruments including patients’ feedback (e.g., too long/complicated sentences, terms not specified enough), the committee considered the AFSS score being the most useful instrument for assessing AF disease burden and symptoms in the ED.

The AFSS and AFS-B scoring systems produced similar outcomes for symptom scores with regard to their agreement, while the values differed for burden scores. Both scores asked similar items to calculate their AF burden score. The AFS-B score includes prior ED visits, hospitalizations and cardioversions, which could be a reason for the deviating outcome values.

Comparing the burden scores, an acceptable mean bias but a high SD and large LOAs were found. Therefore, it was concluded that the measurements were not similar enough to use the scores interchangeably.The LOA for the comparison of the symptom scores was noticeably narrower, and the mean difference was more than 50% smaller compared to the burden score, suggesting that the system scores can be used interchangeably.

The committee decided on the AFSS for the following reasons: (1) both scores seem to be highly sufficient tools without proportional bias; (2) the AFB-strict is recommended in the literature, but it resulted in considerable missing values due to item non-response and led to ambiguities for some patients; (3) according to our literature search, the AFSS is the most widely used[12,13] and best validated scoring system.

The main limitation is the rather small sample size. As this study was designed as a pilot study for the information preferences in patients with atrial fibrillation/flutter and the association with clinical symptoms (INFO-AF) study, there were no formal sample size calculations. A larger sample size might have resulted in better agreement between the methods. For better comparability between the scores, we included all scores in the pilot study. This resulted in a rather long questionnaire with recurring questions and may have led to less precise answers and more missing values.

A future study could benefit from a larger study population and a more streamlined questionnaire with a structured assessment of patients’ own perceptions of the burden of disease and the questionnaire experience.

In conclusion, both the AFSS and AFS-B produce very similar results for symptom scores, while the values for burden scores differed. The AFSS may be more useful because it produces fewer ambiguities and missing answers. Nevertheless, both scores seem to be highly sufficient tools without proportional bias.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria (INFO-AF project, 1617/2019) and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 04299269).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: conceptualization: HH, NS, MP, HD, DR; methodology: HH, NS, MP, HD, AOS, DR; validation: HH, NS, MP, AOS, FC, HD, SS, DR; formal analysis: HH, NS, MP; investigation: HH, NS, MP, AOS, FC, HD, SS, DR; resources: HH, NS, MP, AOS, FC, HD, SS, DR; data curation: NS, MP; writing—original draft preparation: NS; writing—review and editing: HH, NS, MP, AOS, FC, HD, SS, DR; visualization: HH, NS, MP, AOS, FC, HD, SS; supervision: HH, HD, AOS, DR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Reference

Costs of atrial fibrillation in five European countries: results from the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation

Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060

50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study

Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation: A Scientific Statement of JACC: Asia (Part 2)

Forecasting the emergency department patients flow

Variability in patient preferences for participating in medical decision making: implication for the use of decision support tools

Linguistic validation manual for health outcome assessments

Quality of life improves with treatment in the Canadian Trial of Atrial Fibrillation

The impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation: implications for the assessment of investigational therapy

New classification scheme for atrial fibrillation symptom severity and burden

Validating a new quality of life questionnaire for atrial fibrillation patients

Impact of electrical cardioversion on quality of life for patients with symptomatic persistent atrial fibrillation: is there a treatment expectation effect?

Patient-reported outcomes and subsequent management in atrial fibrillation clinical practice: results from the Utah mEVAL AF program