Central venous catheterization (CVC) is an invasive medical procedure used to measure central venous pressure and provides a stable route for continuous drug administration. CVC is widely used in the emergency department and intensive care units. It is typically performed by inserting a catheter through the internal jugular vein (IJV) into the superior vena cava near the right atrium.[1,2] While catheterization is a fundamental skill proficiently performed by healthcare professionals, lethal complications may occasionally occur because of undesirable positioning, depth and diameter.[3,4]

Typically, the IJV is located approximately 1 cm beneath the neck skin. It can be accessed through a central approach by puncturing the apex of Sedillot’s triangle, formed by the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and clavicle, toward the nipple on the same side. The anatomy of the IJV is generally stable. However, variations of the IJV, have been reported in the incidence between 0.4% and 3.3%.[5,6] In 2007, Downie et al[7] defined two types of variations: duplication and fenestration. For a more standardized approach, Mumtaz et al[6] proposed distinguishing bifurcation from duplication depending on the branching position and presented two new types: trifurcation and posterior tributary.

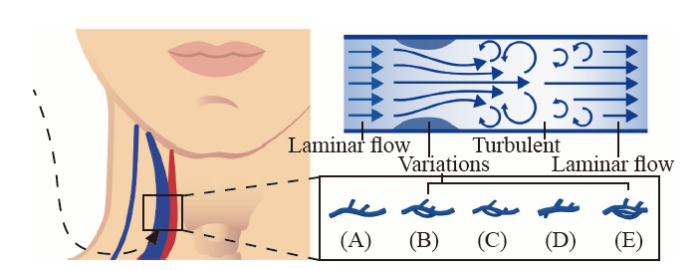

In addition to the risk of carotid artery puncture, this variation can also lead to injury to the accessory nerve. The bifurcated variations create extra space, sometimes allowing the accessory nerve to pass through. Furthermore, variational vessels are associated with turbulence,[8] differing from a normal hemodynamical laminar.[9] Consequently, the altered blood flow dynamics may affect surface projection, diameter, and adjacent structures. This increases the risk of complications resulting from injury to the surrounding structures. Moreover, when measuring central venous pressure using an IJV catheter, complex variations within the IJV may cause changes in blood flow and pressure within the vein (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Anatomical variation of the IJV and altered blood flow. A: normal IJV, which leads to laminar flow; B: duplication; C: fenestration; D: posterior tributary; E: trifurcation. B, C, D, and E may raise a turbulent blood flow due to the stenosis of the vessel theoretically. IJV: internal jugular vein.

In this study, we present three cases of IJV variations, including duplication and fenestration. The clinical features of the published cases were also summarized and analyzed.

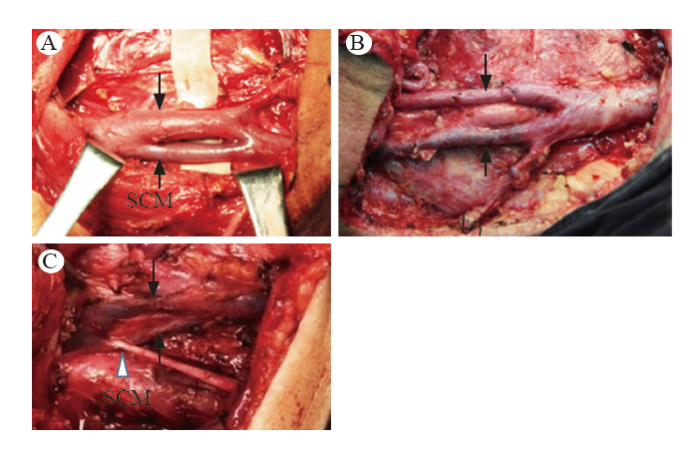

Patient 1, a 53-year-old male presented with a T2N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma on the right floor of the mouth. The patient underwent a right functional neck dissection for cancer. A 5-cm long, fenestrated left IJV with a smaller lateral branch was found during the operation. The right side appeared normal (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative findings of case 1-3. A: patient 1, fenestration of the left IJV; B: patient 2, duplication of the right IJV; C: patient 3, fenestration of the right IJV. IJV: internal jugular vein. SCM: sternocleidomastoid; black arrows show IJV; white arrow shows accessory nerve.

Patient 2, a 42-year-old male presented with a T3N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the right floor of the mouth. Right radical neck dissection was performed due to the disease. During the procedure, a duplication of the right IJV was observed. The bifurcation was approximately 6 cm above the clavicle (Figure 2B).

Patient 3, a 49-year-old male presented with a T3N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the right buccal mucosa. Radical neck dissection of the right side was performed, and a 4.5-cm long, fenestrated right IJV was found during the procedure, with the accessory nerve passing through the space (Figure 2C).

The IJV develops from the anterior cardinal vein. Rossi et al[10] suggested that variations mainly occur during weeks 3-6 of pregnancy when disturbances in the development of the anterior cardinal vein lead to variations. Three proposed theories seek to explain these variations: venous ring stage theory, neural theory, and osseous theory. Venous ring stage theory suggests that the formation of a venous ring around the accessory nerve during IJV development contributes to variations. Neural theory proposes that changes in the position of the accessory nerve can alter IJV development. Osseous theory attributes variations to the presence of variable bony bridges in the jugular foramen. These variations can impact the success rate and accuracy of CVC, highlighting the importance of pre-procedure ultrasound (US) guidance to mitigate complications.

We conducted a comprehensive literature search on IJV variations, and 51 papers with a total of 65 cases were identified. The proportions of duplications (30/65) and fenestrations (30/65) were found to be similar, whereas the occurrences of trifurcation and posterior tributary types were lower (5/65). Among the cases, 12 patients (18%) presented with a spinal accessory nerve passing through this branch. It was observed that cases reported by anatomists and surgeons was 69% (45/65), while those detected through radiological and US examinations accounted for 31% (20/65) of the cases. Furthermore, cases reported from European and American countries constituted 69% (45/65), while cases reported from India and East Asian countries accounted for 21% (14/65) and 9% (6/65) respectively. Analysis of the clinical features of these variations revealed a predominance among male patients (75%), those older than 45 years of age (84%), and those with variations predominantly on the left side (69%) (supplementary Table 1). Similarly, our report on three cases of fenestration and duplication showed the same characteristics. Additionally, there were fewer cases reported by researchers from East Asian countries than from Europe, America and India, suggesting a potential ethnic difference in these variations.

Although the surgical variation of the IJV is well-known among anatomists and surgeons, and the current guidelines suggest the use of US-guided catheterization, a lack of data has shown how this variation affects IJV-related measurements and diagnosis. However, in some emergency circumstances, US may not be available, and the complexity of variations may lead to a difficulty even when using US. Considering the significance of the IJV shape and blood flow in CVC, we propose these variations as potential interference factors and further understanding is needed.

In conclusion, both anatomists and surgeons have acknowledged anatomical variations of the IJV. However, the potential risks posed by these variations in CVC have not been extensively reported, especially for specific ethic groups. The focus of our case series has been expanding our knowledge, reducing complications, and furthering our understanding of these anatomical variations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Lawrence M. J. Best from University College London for providing constructive feedback.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Our study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki statements. The local ethics committee’s approval was obtained (2023-1154).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contribution: All authors read and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

Reference

Central venous pressure line insertion for the primary health care physician

Practical guide for safe central venous catheterization and management 2017

DOI:10.1007/s00540-019-02702-9

PMID:31786676

[Cited within: 1]

Central venous catheterization is a basic skill applicable in various medical fields. However, because it may occasionally cause lethal complications, we developed this practical guide that will help a novice operator successfully perform central venous catheterization using ultrasound guidance. The focus of this practical guide is patient safety. It details the fundamental knowledge and techniques that are indispensable for performing ultrasound-guided internal jugular vein catheterization (other choices of indwelling catheters, subclavian, axillary, and femoral venous catheter, or peripherally inserted central venous catheter are also described in alternatives).

Complete heart block--an underappreciated serious complication of central venous catheter placement

DOI:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2012.06.005

PMID:22809573

[Cited within: 1]

Central venous catheter (CVC) placement is a common bedside procedure that is frequently performed in critically ill patients. More than 5 million CVCs are inserted annually across the United States alone. Procedure-related complications may vary from minor bleeding to life-threatening complications such as arterial perforation and pneumothorax. Cardiac arrhythmias can often occur during the guidewire placement, and bundle-branch blocks have also been reported. We herewith report a case of complete heart block during CVC placement, which is a rare but serious complication of this procedure. Because the patient had a preexisting left bundle-branch block, complete heart block likely resulted from a probable trauma to the right bundle branch during the guidewire insertion.Copyright © 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Perforation of the great vessels during central venous line placement

PMID:7763129

[Cited within: 1]

Placement of central venous lines for the administration of a variety of therapies has become common practice. The most severe complication of this procedure is perforation of a large vessel, with bleeding, infusion of fluids into an extravascular site, and death. It is not clear from currently available data how often this occurs, what risk factors are associated, and how this complication can be avoided.We reviewed the records of all patients who were identified as having perforation of a major vessel during central venous line placement occurring between 1986 and 1993 at the University Hospital, the major teaching facility of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver. Data collected included the age and sex of the patient, diagnosis, type of catheter and site of placement, operator means and time to the diagnosis of perforation, and outcome.Eleven such complications were identified and 10 of them are reviewed in detail. The overall incidence was less than 1%. Most complications occurred when the right subclavian vein approach was attempted, and they were thought to result from guidewire kinking during advancement of a vessel dilator. All medical specialties and levels of training were involved. Four of 10 patients died of immediate or subsequent complications of the perforation.Perforation of a great vessel is an uncommon, but often fatal, complication of central venous line placement. It occurs most often, when using the right subclavian vein approach, from guidewire kinking. Physicians performing this procedure should have formal training in central venous catheterization and be aware of this complication, its presumed cause, diagnosis, and treatment.

High duplication of the internal jugular vein:clinical incidence in the adult and surgical consequences, a report of three clinical cases

Surgical review of the anatomical variations of the internal jugular vein: an update for head and neck surgeons

DOI:10.1308/rcsann.2018.0185

PMID:30322289

[Cited within: 2]

The internal jugular vein is one of the major vessels of the neck. The anatomy of this vessel is considered to be relatively stable. It is an important landmark for head and neck surgeons as well as the anaesthetists for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.We present two case reports of the posterior tributary of the internal jugular vein and review the surgical literature regarding anatomical variations of the vein.A total of 1197 patients from 27 published papers were included in this review. Of these patients, 99.6% had neck surgery and the rest were cadaveric dissections. Anatomical variations of the internal jugular vein were found in 2% of the patient cohort (n = 40). The majority of these patients had either bifurcation or fenestration of the vein. The posterior tributary of the internal jugular vein is unusual and is scarcely reported in the literature (three cases). Knowledge of variations in the anatomy of the internal jugular vein assists surgeons in avoiding complications during neck surgery and preventing morbidity. Two rare cases of posterior branching of the internal jugular vein and experience of other surgeons are demonstrated in this extensive review.

Bilateral duplicated internal jugular veins: case study and literature review

PMID:16838288

[Cited within: 1]

A rare bilateral duplication of the internal jugular vein (IJV) was discovered during cadaveric dissection. From each jugular foramen, a single IJV descended to the level of the hyoid bone then divided into medial and lateral veins. The medial IJVs traveled in the carotid sheath; the lateral IJVs coursed posterolateral to the sheath across the lateral cervical region (posterior triangle) of the neck. On the right side, medial and lateral IJVs entered the subclavian vein separately. C2-C3 anterior rami and the suprascapular artery passed between the medial and lateral IJVs. The right external jugular vein passed aberrantly between the heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) into the subclavian vein anterior to the lateral IJV. On the left side, the medial IJV drained into a large bulbous jugulovertebrosubclavian (JVS) sinus that received six main vessels. The lateral IJV diverged posterolaterally toward the border of the trapezius muscle, received the transverse cervical vein, and then turned sharply anteromedially to drain into the JVS sinus. The lateral IJV also gave an aberrant additional large vein that passed laterally around the omohyoid muscle before entering the JVS sinus. The left external jugular vein paralleled the anterior border of SCM before passing posterolaterally to terminate in the JVS sinus. Jugular vein anomalies of this magnitude are very rare. Determining the frequency of multiple IJVs is hampered by inconsistent terminology. We suggest that IJV duplication differs from fenestration anatomically and, potentially, developmentally. Criteria for characterizing IJV duplication and fenestration are proposed. The mechanism of development and the clinical significance of multiple IJVs are discussed.

Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives

Turbulent flow in constricted blood vessels: quantification of wall shear stress using large eddy simulation

Internal jugular vein phlebectasia and duplication: case report with magnetic resonance angiography features