In patients with lagophthalmos due to eyelid trauma, it is imperative to ensure adequate closure of the eye to protect the ocular surface. Sometimes it is difficult to surgically close eyelids by conventional methods of tarsorrhaphy, such as intermarginal suture tarsorrhaphy, Week’s tarsorrhaphy, and tongue-in-groove tarsorrhaphy. We need intact eyelid tissues to perform these procedures and might not be possible in patients with severe lagophthalmos due to lost/damaged eyelid tissues either due to deficient length of tissues or increased tension at the wound site, which can result in surgical failure.[1]

Patients with acute presentation of injury with extensive eyelid and periorbital trauma usually have associated tissue loss and ocular surface injury. An attempt to perform definitive surgery for eyelid reconstruction using grafts and/or flaps, as an emergency procedure, is not always feasible or, if done, can result in more damage to the tissues because of high failure rates.[2] Herein, we describe posterior lamellar tarsorrhaphy (PLT), a novel and simple surgical approach that can be performed as an emergency procedure to protect the ocular surface in acute presentation of patients with severe lagophthalmos following extensive trauma/burns.

METHODS

This was a retrospective study of patients with early presentation to eye emergency with severe lagophthalmos due to extensive eyelid and periorbital burns or trauma who underwent PLT at our center between October 2018 and December 2020. The study adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained.

Eight patients, all males with ages ranging from 8 to 63 years, were included. Trauma was due to thermochemical injury in 4 patients, road traffic accidents in 3 patients, and electrocution injury in 1 patient. Except 2 patients who presented on day 4 and day 10 after trauma, the remaining 6 patients were operated on within 24 h of injury. Three patients had bilateral involvement, 3 had right eye involvement, and 2 had left eye involvement. In patients with bilateral involvement, only 1 patient underwent PLT for both eyes. Of them, 1 patient had mild lagophthalmos, and the other patient had severe injury with hypotonus globe and no visual prognosis in the second eye, so only one eye underwent PLT. Therefore, a total of 9 eyes underwent PLT in our study.

RESULTS

In the 9 operated eyes, visual acuity at presentation was < 1/60 in 6 eyes, 3/60 in 1 eye, 6/18 in 1 eye, and 1 child with bilateral trauma was not cooperative for vision assessment. All patients had severe trauma to the eyelids, with lagophthalmos in 9 eyes (14.0±4.7 mm) and ocular surface injury in all eyes. Anterior lamellar tissue was swollen and friable, with areas of nonviable tissue and/or loss in 15 out of 18 (83.33%) eyelids (9 eyes). At least 1 eyelid margin was lost in all the operated eyes, and both eyelid margins were lost in 6 eyes. Complete absence of upper and lower eyelid anterior lamellar tissues was found in 3 eyes along with loss of posterior lamella until fornix in 2 patients and partial loss of posterior lamella in 1 patient. Six eyes had partial loss of anterior lamella with preserved posterior lamellar tissues. Extensive periorbital injury was present in all operated eyes, and full-face burns were present in two cases, with one of them having 45% total burn surface area (TBSA).

Exposure keratopathy was present in all operated eyes, with epithelial defects and infiltration in 6 eyes, limbal ischemia in 3 eyes, and corneal melt in 2 eyes. Reconstruction using a flap or grafting procedure did not seem to be a viable option in these patients. PLT was performed as an eye-saving procedure. In addition, periorbital laceration repair surgery was performed in 4 patients, and amniotic membrane grafts of both eyes were performed in 1 patient.

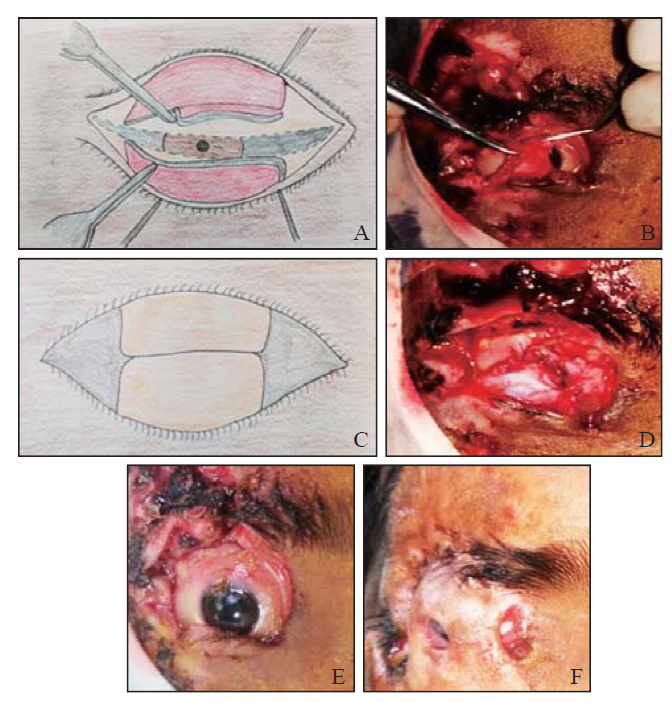

PLT was performed by splitting the anterior and posterior lamellae by incision at the gray line or skin-conjunctival junction in patients with lost eyelid margins. The incision was made in the central part, aiming for closure of at least half of the horizontal aperture. The margins of the posterior lamellae (tarso conjunctiva) of upper and lower eyelids were made raw by excising 1 mm of margin tissues. In the lower eyelid, dissection was extended deep until the lower border of the tarsus, and the posterior lamellar flap was mobilized by giving medial and lateral vertical cuts until the lower tarsal border and advanced (Figures 1 A and B). The raw margins of both the posterior lamellae were brought together, and if found under tension, then a similar mobilization and advancement of the posterior lamellar flap of the upper eyelid was also carried out. The raw surfaces of the posterior lamellae were sutured together using interrupted 6-0 polyglactin sutures (Figures 1 C and D). The traumatized/deficient anterior lamellae were left to heal with secondary intention. The sutures were removed after 10 d. Postoperatively, all patients were advised to use topical lubricants and antibiotics. Depending on the extent of injury, other supportive treatment was also given. Split-thickness skin grafting of the abdomen, both thighs and right forearm, was performed in 1 patient who had associated 45% TBSA.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the surgical technique. A: sketch diagram shows advancement of posterior lamellae after splitting the eyelid margins and giving vertical lateral and medial cuts until borders of the tarsal plates in upper and lower eyelids, respectively; B: clinical photograph shows advancement of posterior lamellar flap of lower eyelid after giving medial and lateral vertical cuts till the lower tarsal border; C: sketch diagram shows the raw margins of both the posterior lamellae brought together and sutured using interrupted sutures; D: clinical photograph of same patients with upper and lower posterior lamellar flaps being advanced and sutured together using interrupted 6-0 polyglactin sutures; the traumatized/deficient anterior lamellae were left as such to heal with secondary intention; E: preoperative picture showing full thickness loss of upper and partial loss of lower lid with residual lid margin tissues, laterally with periorbital laceration wound with tissue loss and eschar formation; F: intact posterior lamellar tarsorrhaphy at 3-month follow-up in the same patient.

On follow-up, ocular surface symptoms resolved, and corneal re-epithelialization was achieved within 4-6 weeks in all patients. A patient with thermochemical injury and severe ocular surface injury had limbal ischemia with complete epithelial defect and infiltration, vision was light perception in oculus dexter (OD) and total corneal melt with no light perception in oculus sinister (OS). He underwent amniotic membrane grafting with PLT as a primary procedure in both eyes; at the 3-week follow-up, corneal grafting with resuturing of PLT was performed in both eyes. His vision recovered to 6/60 OD with PLT in place, and he had no vision OS at the 6-month follow-up. In the rest of the operated eyes, visual acuity improved to > 6/18 in 6 eyes and 6/60 in 1 eye. Four eyes underwent full-thickness skin grafting for cicatricial ectropion and lagophthalmos as a secondary procedure at a mean follow-up duration of 5.4±0.7 months. The mean follow-up duration of patients in our study was 6.5±3.4 months (range 3-15 months). At the last follow-up, out of 9 operated eyes, 5 eyes had partial corneal opacity, 3 eyes had clear cornea, and 1 eye with total corneal melt at presentation went into phthisis bulbi. None of the patients required a repeated tarsorrhaphy procedure or had a nonhealing epithelial defect or progression to corneal melt/perforation. Three eyes are still awaiting skin grafting procedures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

DISCUSSION

Eyelid trauma/burns account for approximately 65% of facial trauma, and 15% of these patients become blind if not treated in a timely manner.[1,3] An important aspect in the early management of eyelid trauma is to ensure adequate closure and lubrication of the ocular surface, which prevents as well as halts exposure and trauma-related corneal complications.[4] Studies show that surgeons prefer to perform primary reconstruction with grafts and/or flaps in burns/trauma patients, instead of tarsorrhaphy.[1,5,6] In most of these reports, the intervention was performed within 2-4 weeks of presentation.[6] The main reason for avoidance of permanent tarsorrhaphy was that the procedure can lead to eyelid margin irregularity, trichiasis, entropion, etc. In contrast, Frank et al[1] mentioned the use of tarsorrhaphy in some unavoidable situations with severe eyelid damage. Delayed reconstructive procedures are known to have disadvantages of hypertrophic scarring and deformities, whereas advantages are better planning and success of a full-thickness graft. [7,8]

In acute presentation of patients with severe lagophthalmos due to eyelid and periorbital trauma, where a flap cannot be raised and/or if the recipient eyelid bed has friable and ischemic tissues with tissue loss, the primary reconstructive procedure using grafts and/or flaps becomes difficult. In this small subset of patients, tarsorrhaphy remains the mainstay of emergency care for protection of the ocular surface. All our patients had associated damage to one or both eyelid margins with other surrounding tissue involvement, as already mentioned, where damage to the anatomy of the eyelid margin because of the procedure was not the main concern. The technique resulted in a strong fusion because the posterior lamellar flaps were mobilized free and the wound was not under tension. Furthermore, we achieved adequate ocular surface coverage that led to healing of the cornea with useful visual recovery in most of the patients. We observed that the posterior lamella, being a hidden part of the eyelid, was less damaged/deficient than the anterior lamella because we could advance it freely with our technique.

Previous reports are available on mobilization of remaining conjunctiva from the eyelid and fornices and suturing them together, and even a study describes advancement of levator muscle along with skin graft to cover the ocular surface in patients with severely traumatized/loss of eyelid tissues.[5,9,10]

CONCLUSIONS

PLT provides adequate coverage of the ocular surface, which remains a priority over iatrogenic damage by the procedure in the acute presentation of patients with severe lagophthalmos due to loss of eyelid and periorbital tissues where primary repair or reconstructive procedures are difficult or not possible. It is not a procedure of choice over other less damaging procedures of tarsorrhaphy or in cases where it can be completely avoided.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr Saloni Gupta, Northern Railway Central Hospital, New Delhi, for her assistance in the hand-drawn diagrams illustrating the surgical technique.

Funding: None

Ethical approval: The study was approved by Ethics Board of Dr Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and written informed consent was obtained.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: NP: conceived and designed the work and did final approval; DD: data analysis and interpretation; SM: literature search and manuscript draft review; PS: critical revision and data acquisition; SA: wrote the manuscript and acted as a gurantor.

Reference

The early treatment and reconstruction of eyelid burns

DOI:10.1097/00005373-198310000-00005 URL [Cited within: 4]

Management of difficult pediatric facial burns: reconstruction of burn-related lower eyelid ectropion and perioral contractures

DOI:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318175f451

PMID:18650718

[Cited within: 1]

Despite significant burn treatment advances, modern multidisciplinary care, and improved survival after burns, facial burn scars remain clinically challenging. Achieving a successful reconstruction requires a comprehensive approach, entailing many advanced techniques with an emphasis on preserving function and balancing intricate aesthetic requirements. Pediatric facial burns present the same reconstructive challenges seen in adults, with additional developmental and psychologic concerns. In this paper, we describe the basic principals of facial burn care in the pediatric burn population, with a specific focus on lower-eyelid burn ectropion and oral commissure burn scar contracture leading to microstomia. Several cases are demonstrated.

Ophthalmological complications as a manifestation of burn injury

PMID:8634121

[Cited within: 1]

Facial burns are a frequent component of the presentation of victims who have sustained thermal trauma, reportedly occurring in 20 per cent of burn patients. Even apparently 'f2p4r' facial injuries might well be associated with significant ocular trauma. A retrospective review of 865 patients admitted to our burn centre showed 22 per cent (192) with facial burns. Ocular involvement, defined as globe or eyelid pathology, was present in 15 per cent (127) of these patients. The aetiology and spectrum of ocular injuries is reviewed with lid burns and subsequent lid contractures, accounting for over 50 per cent of ocular complications. Serious ocular pathology necessitating enucleation occurred in only two patients. The difficulties encountered in performing a complete ophthalmological examination in the presence of facial burns are presented in conjunction with a recommended therapeutic plan.

Ophthalmological sequelae of thermal burns over ten years at the Alfred Hospital

DOI:10.1097/00002341-200205000-00008 URL [Cited within: 1]

The management of eyelid burns

DOI:10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.02.009

PMID:19422964

[Cited within: 2]

Eyelid involvement is common in facial burns. Ocular sequelae, including corneal ulceration, are usually preventable and secondary to the development of eyelid deformities, exposure keratopathy, and rarely, orbital compartment syndrome. Early ophthalmic review and prophylactic ocular lubrication is mandatory in burns involving the eyelids. Early surgical intervention, often requiring repeat procedures, is indicated if eyelid retraction causing corneal exposure occurs. Permanent visual impairment is rare with such prompt management. No binding aphorisms exist regarding the tissue used for eyelid reconstruction, with each case requiring an individual approach based on available skin. This review article covers the principles of ophthalmic management in addition to intermediate and long-term management of eyelid burns.

Acute surgical vs non-surgical management for ocular and peri-ocular burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis

DOI:10.1186/s41038-019-0161-4

PMID:31497611

[Cited within: 2]

Burn-related injury to the face involving the structures of the eyes, eyelids, eyelashes, and/or eyebrows could result in multiple reconstructive procedures to improve functional and cosmetic outcomes, and correct complications following poor acute phase management. The objective of this article was to evaluate if non-surgical or surgical interventions are best for acute management of ocular and/or peri-ocular burns.This systematic review and meta-analysis compared 272 surgical to 535 non-surgical interventions within 1 month of patients suffering burn-related injuries to 465 eyes, 253 eyelids, 90 eyelashes, and 0 eyebrows and evaluated associated outcomes and complications. The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were systematically and independently searched. Patient and clinical characteristics, surgical and medical interventions, outcomes, and complications were recorded.Eight of the 14,927 studies queried for this study were eligible for the systematic review and meta-analysis, with results from 33 of the possible 58 outcomes and complications using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) and Cochrane guidelines. Surgery was associated with standard mean differences (SMD) 0.44 greater visual acuity on follow-up, SMD 1.63 mm shorter epithelial defect diameters on follow-up, SMD 1.55 mm greater changes in epithelial diameters from baseline, SMD 1.17 mm smaller epithelial defect areas on follow-up, SMD 1.37 mm greater changes in epithelial defect areas from baseline, risk ratios (RR) 1.22 greater numbers of healed epithelial defects, RR 11.17 more keratitis infections, and a 2.2 greater reduction in limbal ischemia compared to no surgical intervention.This systematic review and meta-analysis found that compared to non-surgical interventions, acute surgical interventions for ocular, eyelid, and/or eyelash burns were found to have greater visual acuity on follow-up, shorter epithelial defect diameters on follow-up, greater changes in epithelial diameters from baseline, smaller epithelial defect areas on follow-up, greater changes in epithelial defect areas from baseline, greater numbers of healed epithelial defects, more keratitis infections, and a greater reduction in limbal ischemia, possibility preventing the need of a future limbal stem cell transplantation.

Full-thickness grafting of acute eyelid burns should not be considered taboo

PMID:10456512

[Cited within: 1]

Split-thickness skin grafts are commonly used for the treatment of acute eyelid burns; in fact, this is dogma for the upper lid. Ectropion, corneal exposure, and repeated grafting are common sequelae, almost the rule. It was hypothesized that for acute eyelid burns, the use of full-thickness skin grafts, which contract less than split-thickness skin grafts, would result in a lower incidence of ectropion with less corneal exposure and fewer recurrences. The records of all patients (n = 18) who underwent primary skin grafting of acutely burned eyelids (n = 50) between 1985 and 1995 were analyzed retrospectively. There were 10 patients who received full-thickness skin grafts (12 upper lids, 8 lower lids) and 8 patients who received split-thickness skin grafts (15 upper lids, 15 lower lids). Three of 10 patients (30 percent) who received full-thickness skin grafts and 7 of 8 patients (88 percent) who received split-thickness skin grafts developed ectropion and required reconstruction of the lids (p = 0.02). No articles were found substantiating the concept that only split-thickness grafts be used for acute eyelid burns. The treatment of acute eyelid burns with full-thickness rather than split-thickness skin grafts results in less ectropion and fewer reconstructive procedures. It should no longer be considered taboo and should be carried out whenever possible and appropriate.

Secondary correction of the burned eyelid deformity

PMID:358237

[Cited within: 1]

We describe our experience in late reconstructions of 35 burned eyelids. On this basis we advocate wide, aggressive release of all scar contractures, including the distal part of the levator when necessary. To cover the resultant defects we use generous full-thickness skin grafts, if available, for both the upper and lower lids. Rarely has a tarsorrhaphy been required, and properly constructed dressings provide satisfactory lid immobilization and permit conjunctival hygiene. During the postoperative period the vision need not be obstructed by a tarsorrhaphy, Frost sutures, or the dressings.

Cicatricial ectropion due to thermal burns of the eyelids

In: Mauriello JA, eds. Unfavourable results of eyelid and lacrimal surgery, prevention and management. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann,

Thermal eyelid burns. Oculoplastics, orbital and reconstructive surgery