Dear editor,

Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS), a rare complication of autoimmune inflammatory diseases, is mainly associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with an occurrence in 1%-2% of cases.[1] It is characterized by restrictive defects on pulmonary function tests (PFTs) associated with reduced lung volume. SLS has also been reported in cases of primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS),[2,3] scleroderma,[4] rheumatoid arthritis,[5] mixed connective tissue disease,[6] and undifferentiated connective tissue disease. Herein, we present three case reports of SLS, including two patients with SLE and one patient with adult-onset Still's disease (AOSD) (Table 1).

Table 1. Main clinical characteristics of the three patients in this study

| Variables | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 26 | 53 | 68 | |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female | |

| Primary disease | SLE | SLE | AOSD | |

| Duration of the primary disease, years | 12.0 | 2.0 | 0.4 | |

| Treatment before the diagnosis of SLS | Prednisone, HCQ, TAC | Prednisone, HCQ | Prednisone | |

| Presenting features of SLS | Dyspnea, cough | Dyspnea, chest pain | Dyspnea | |

| Other clinical manifestations | Mucocutaneous, arthritis, fever, nephritis | Mucocutaneous, arthritis, nephritis, cardiac valvular dysfunction | Fever, mucocutaneous | |

| Autoantibodies | ANA, Smith, RNP, SSA, Ro-52, SSB, ARPA | ANA, dsDNA, SSA, Ro-52, SSB, | None | |

| Chest CT | Aatelectasis, diaphragm elevation, pleural effusion, pleural thickening | Aatelectasis, pleural effusion | Atelectasis, diaphragm elevation | |

| SLEDAI | 10 | 20 | / | |

| Pulmonary function test | ||||

| Forced vital capacity, % | 62.5 | 59.1 | 72.4 | |

| Total lung capacity, % | 69.9 | 72.2 | 66.9 | |

| FEV1, % | 67.3 | 65.0 | 74.8 | |

| DLCO, % | 42.4 | 55.2 | 50.4 | |

| Treatment | MP 60 mg/d+CYC+TAC | MP 500 mg/d+CYC+IVIG | MP 160 mg/d+CYC | |

| Follow-up time, months | 36 | 8 | 6 | |

| Clinical outcome | Improved | Improved | Improved | |

| PFT outcome | Improved | Improved | Not improved | |

| HRCT outcome | Improved | Improved | Not improved | |

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; AOSD: adult onset Still's disease; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; TAC: tacrolimus; CT: computed tomography; SLEDAI: SLE disease activity index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; MP: methylprednisolone; CYC: cyclophosphamide; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; PFT: pulmonary function test; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography.

CASE 1

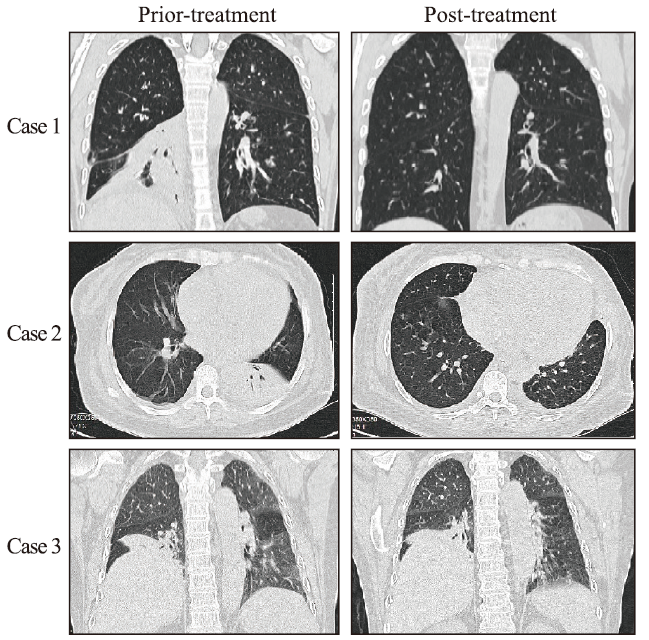

A 14-year-old girl with fever, facial erythema, arthritis, and proteinuria was diagnosed with SLE in 2006. In May 2018, she presented with exertional dyspnea, cough, and rash recurrence. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed right lower lobe atelectasis, elevated right diaphragm, mild bilateral pleural effusion, and pleural thickening, without interstitial pneumonia (Figure 1). PFTs showed forced vital capacity (FVC) 62.5%, total lung capacity (TLC) 69.9%, forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) 67.3%, and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) 42.4%, consistent with a restrictive pattern. SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) was 10 (high disease activity). Methylprednisolone (MP) 60 mg/d was initiated and her dyspnea and cough were significantly improved after 2 weeks. Chest CT also showed improvement in atelectasis and elevated diaphragm. Pulse therapy of cyclophosphamide (CYC) was performed monthly. In January 2019, MP was maintained at 8 mg/d and CYC was discontinued after the accumulated dose reached 5.4 g. PFTs revealed FVC 78.6%, TLC 76.6%, FEV1 73.0%, and DLCO 49.9%, representing marked improvements. At the most recent evaluation in May 2021, she was in good condition on MP 4 mg/d, hydroxychloroquine 0.2 g/d, and tacrolimus 2 mg/d.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography of the three patients in this case series.

CASE 2

In January 2021, a 53-year-old woman diagnosed with SLE presented with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and lower extremity edema, without fever or cough. Chest CT showed right lower and left upper lobe atelectasis and bilateral pleural effusion, without interstitial pneumonia (Figure 1). PFTs confirmed a restrictive pattern with FVC 59.1%, TLC 72.2%, FEV1 65.0%, and DLCO 55.2%. She had kidney and heart involvement at the same time and very high SLEDAI of 20. MP 500 mg/d and intravenous immunoglobulin 20 g/d for 3 d were given simultaneously, followed by MP 80 mg/d and CYC 0.8 g monthly as continued therapy. Her symptoms, including dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain, improved significantly. Repeated chest CT showed improvement in atelectasis and pleural effusion. In September 2021, 8 pulses of CYC (accumulated dose 6.4 g) were completed and MP was gradually tapered to 8 mg/d. FVC increased to 76.6% with TLC 79.9%, FEV1 81.5%, and DLCO 69.5%, and lung CT showed complete recovery from atelectasis and pleural effusion.

CASE 3

A 68-year-old woman presented with remitting fever and transient rash since September 2020, and was diagnosed with AOSD according to the Cush criteria. She had a good response to full-dose MP, but fever and rash recurred when glucocorticoid was withdrawn by herself. In January 2021, she developed progressive aggravating dyspnea. Chest CT showed obvious elevated right diaphragm and right lower lobe atelectasis (Figure 1). PFTs confirmed a restrictive pattern with FVC 72.4%, TLC 66.9%, FEV1 74.8%, and DLCO 50.4%. Electroneurographic studies of the phrenic nerves showed bilateral partial motor neuropathy that was more severe on the right side. The patient initiated treatment with MP 160 mg/d and CYC 0.8 g monthly. Fever and rash were gradually relieved. Unfortunately, CYC was discontinued after 3 pulses because of side effects. In the following 6 months, MP was gradually tapered to 8 mg/d. Dyspnea was mildly alleviated, but there were no significant improvements in PFTs and chest CT.

DISCUSSION

We searched the National Library of Medicine PubMed database for relevant literature using the key term “shrinking lung syndrome”. A total of 223 SLE patients and 9 non-SLE patients (supplementary Table 1) were obtained from 70 articles published between 1965 and June 2021 in English, French, and Spanish. Together with the three patients reported in this article, the demographic and clinical characteristics of 225 SLE patients and 10 non-SLE patients are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics and outcome of 225 SLE patients and 10 non-SLE patients with shrinking lung syndrome

| Variables | SLE (n=225) | Non-SLE (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||

| Age, years, median (range) | 32 (11-69) | 48 (15-68) |

| Sex (female/male) | 208/17 | 9/1 |

| Duration of the primary disease, years, median (range) | 5.4 (0-33.0) | 2.8 (0-10.0) |

| Clinical manifestations, n (%) | ||

| Dyspnea | 201/203 (99.0) | 10/10 (100.0) |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 127/160 (79.4) | 6/10 (60.0) |

| Cough | 38/118 (32.2) | 2/10 (20.0) |

| Image, PFT, and EMG findings, n (%) | ||

| Diaphragm elevation | 186/204 (91.2) | 9/10 (90.0) |

| Pleural effusion | 71/204 (34.8) | 5/10 (50.0) |

| Atelectasis | 31/204 (15.2) | 7/10 (70.0) |

| Pleural thickening | 24/204 (11.7) | 2/10 (20.0) |

| PFT restrictive pattern | 198/205 (96.6) | 10/10 (100.0) |

| Phrenic nerve desfunction | 3/16 (18.8) | 3/4 (75.0) |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||

| Glucocorticoids | 166/175 (94.9) | 10/10 (100.0) |

| Azathioprine | 46/175 (26.3) | 3/10 (30.0) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 33/175 (18.9) | 2/10 (20.0) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 20/175 (11.4) | 1/10 (10.0) |

| Methotrexate | 9/175 (5.1) | 0 |

| Rituximab | 18/175 (10.3) | 3/10 (30.0) |

| Beliuumab | 2/175 (1.1) | 0 |

| Outcome, n (%) | ||

| Clinical improvement | 78/106 (73.6) | 10/10 (100.0) |

| PFT improvement | 37/68 (54.4) | 6/8 (75.0) |

| Image improvement | 10/46 (21.7) | 6/8 (75.0) |

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; PFT: pulmonary function test; EMG: electromyogram.

The physiopathology of SLS has not been well described. The following hypotheses have been developed: (1) excessive surface tension related to loss of surfactant on alveolae; (2) respiratory muscle weakness; (3) diaphragmatic myopathy; (4) phrenic nerve dysfunction; (5) pleural adhesion; and (6) pleural inflammation-related inhibition of deep inspiration by neural reflexes.[7] Unfortunately, none of these hypotheses have been confirmed to date. Among them, phrenic nerve dysfunction is considered an important cause of SLS, existing in 30% of reported cases. Phrenic nerve involvement is one of the localizations for mononeuritis multiplex that can be induced by primary diseases like SLE and pSS. Neurological complications have also been described in AOSD, with involvement of the peripheral and cranial nerves.[8] Case 3 presented with recurrent fever and progressive aggravating dyspnea without pleuritic chest pain and pleural effusion. Therefore, phrenic nerve dysfunction may be responsible for her SLS.

Diagnosis of SLS relies on the following factors: unexplained dyspnea, reduced lung volume, and restrictive defects on PFTs, without simultaneous interstitial, alveolar, or pulmonary vascular disease. There is no consensus treatment for SLS in the absence of large sample clinical trials. Medium or high doses of glucocorticoids are the first-line treatments to reduce inflammation and regulate immunity. Azathioprine and CYC were the most frequently reported immunosuppressive agents.[9] Rituximab and belimumab were also effective in a few severe or refractory cases.[10] Theophylline and beta-agonists were beneficial for some patients to increase diaphragmatic strength and decrease diaphragmatic fatigue. In most reported cases, lung function was improved after timely and active treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

SLS is a rare respiratory manifestation in various autoimmune inflammatory diseases. The main characteristics of SLS are restrictive patterns on PFTs and reduced lung volume on chest imaging. Glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents are effective in most patients with CTD-related SLS. Heightened awareness and early identification of SLS are important to improve the disease prognosis.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by our local ethics committee and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We obtained written informed consent from the patients to publish their data.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributors: XCC proposed the study and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

Reference

Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: a single-centre experience

DOI:10.1177/0961203317722411

PMID:28758573

[Cited within: 1]

Introduction Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), characterized by decreased lung volumes and extra-pulmonary restriction. The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics of SLS in our lupus cohort with emphasis on prevalence, presentation, treatment and outcomes. Patients and methods Patients attending the Toronto Lupus Clinic since 1980 ( n = 1439) and who had pulmonary function tests (PFTs) performed during follow-up were enrolled ( n = 278). PFT records were reviewed to characterize the pattern of pulmonary disease. SLS definition was based on a restrictive ventilatory defect with normal or slightly reduced corrected diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) in the presence of suggestive clinical (dyspnea, chest pain) and radiological (elevated diaphragm) manifestations. Data on clinical symptoms, functional abnormalities, imaging, treatment and outcomes were extracted in a dedicated data retrieval form. Results Twenty-two patients (20 females) were identified with SLS for a prevalence of 1.53%. Their mean age was 29.5 ± 13.3 years at SLE and 35.7 ± 14.6 years at SLS diagnosis. Main clinical manifestations included dyspnea (21/22, 95.5%) and pleuritic chest pain (20/22, 90.9%). PFTs were available in 20 patients; 16 (80%) had decreased maximal inspiratory (MIP) and/or expiratory pressure (MEP). Elevated hemidiaphragm was demonstrated in 12 patients (60%). Treatment with prednisone and/or immunosuppressives led to clinical improvement in 19/20 cases (95%), while spirometrical improvement was observed in 14/16 patients and was mostly partial. Conclusions SLS prevalence in SLE was 1.53%. Treatment with glucocorticosteroids and immunosuppressives was generally effective. However, a chronic restrictive ventilatory defect usually persisted.

Shrinking lung syndrome in primary Sjögren syndrome

Shrinking lung syndrome and pleural effusion as an initial manifestation of primary Sjögren's syndrome

Shrinking lung syndrome in systemic sclerosis

DOI:10.1002/art.11393 URL [Cited within: 1]

Shrinking lung syndrome as a manifestation of pleuritis: a new model based on pulmonary physiological studies

DOI:10.3899/jrheum.121048

PMID:23378468

[Cited within: 1]

The pathophysiology of shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is poorly understood. We sought to define the structural basis for this condition through the study of pulmonary mechanics in affected patients.Since 2007, most patients evaluated for SLS at our institutions have undergone standardized respiratory testing including esophageal manometry. We analyzed these studies to define the physiological abnormalities driving respiratory restriction. Chest computed tomography data were post-processed to quantify lung volume and parenchymal density.Six cases met criteria for SLS. All presented with dyspnea as well as pleurisy and/or transient pleural effusions. Chest imaging results were free of parenchymal disease and corrected diffusing capacities were normal. Total lung capacities were 39%-50% of predicted. Maximal inspiratory pressures were impaired at high lung volumes, but not low lung volumes, in 5 patients. Lung compliance was strikingly reduced in all patients, accompanied by increased parenchymal density.Patients with SLS exhibited symptomatic and/or radiographic pleuritis associated with 2 characteristic physiological abnormalities: (1) impaired respiratory force at high but not low lung volumes; and (2) markedly decreased pulmonary compliance in the absence of identifiable interstitial lung disease. These findings suggest a model in which pleural inflammation chronically impairs deep inspiration, for example through neural reflexes, leading to parenchymal reorganization that impairs lung compliance, a known complication of persistently low lung volumes. Together these processes could account for the association of SLS with pleuritis as well as the gradual symptomatic and functional progression that is a hallmark of this syndrome.

Shrinking lung syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter collaborative study of 15 new cases and a review of the 155 cases in the literature focusing on treatment response and long-term outcomes

DOI:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.021

PMID:27481038

[Cited within: 1]

Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare respiratory manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), characterized by dyspnea, chest pain, elevated hemidiaphragm and a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests. Here, we report 15 new observations of SLS during SLE and provide a systematic literature review. We studied the clinical, biological, functional and morphologic characteristics, the treatments used and their efficacy.The inclusion criteria were all patients with SLE defined by the American College of Rheumatology criteria Hochberg (1997), associated with a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests. The exclusion criteria were all differential diagnoses of restrictive patterns, including obesity and pulmonary fibrosis. The patients were recruited from local databases through chest physicians, rheumatologists and internists. The data for the literature review were extracted from the Medline database using "shrinking lung syndrome" and "lupus" as key words.All 15 new cases were women with a median age at SLS onset of 27years old (range 17-67years). All of them complained of dyspnea and all but one of chest pain. The antibodies were similar to those found in SLE, although the anti-SS-A was positive in 10 of 13 cases. Thoracic imaging showed elevated hemidiaphragm (12/15) and/or basal atelectasia (8/15). All of the patients had an isolated restrictive pattern on PFT, with a median decrease >50% of lung volume. All of the patients were treated, using corticosteroids (11/15), immunosuppressive drugs (8/15), beta-mimetics (2/15), physiotherapy (3/15) and/or colchicine (1/15). Improvement was described in 9 of 12 patients and stability in 3 of 12. We extracted 155 cases of SLE-associated SLS from the Medline database. The clinical, biological and functional parameters were similar to our cases. Clinical improvement was described in 48 of 52 cases (94%) and PFT improvement in 36 of 47 cases. Worsening occurred in 4 cases.SLS is a rare SLE manifestation. Pain and parietal inflammation seem to play important pathogenic roles. Steroids and antalgics are the most commonly used therapies with good responses. There is no proof of efficacy with immunosuppressive drugs for this entity. Rituximab can be discussed after failure of corticosteroids, as well as antalgics, theophylline and beta-mimetics.Copyright © 2016 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Miller Fisher syndrome in adult onset Still's disease: case report and review of the literature of other neurological manifestations

Shrinking lung syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus: a case series and literature review

DOI:10.1093/qjmed/hcx204

PMID:29088421

[Cited within: 1]

Shrinking lung syndrome (SLS) is a rare manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus, characterized by progressive dsypnoea, reduced lung volumes and associated restrictive lung physiology. Here, we provide two previously unreported cases, and review the available literature on the pathophysiology, clinical features and management of SLS. Effective treatment can prevent further deterioration or lead to improvement in abnormal lung function. A heightened awareness of SLS and its management is therefore required to prevent disease progression and increased morbidity.

Shrinking lung syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in 3 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

DOI:10.1097/RHU.0000000000001132 URL