INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery (SMA) dissection (SISMAD), a rare disease presenting with one of the most common symptoms (acute abdominal pain) in the emergency department (ED), is considered to be a vascular disease with a potentially fatal pathology.[1⇓-3] Non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is a crucial clinical screening modality in the ED for acute abdominal pain.[4,5] Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) or CT angiography (CTA) is the diagnostic test of SISMAD.[1,6] Owing to the rarity of SISMAD and the invasiveness and expensiveness of CECT or CTA, it is not common that abdominal pain patients immediately undergo CECT or CTA to diagnose or rule out SISMAD after non-enhanced CT.[4] In our hospital, there are approximately 1,500 abdominal pain patients per month, about 980 undergo non-enhanced CT, only approximately 120 patients undergo CECT or CTA, and only 1.2 patients per month are diagnosed with SISMAD. Hence, early diagnosis of SISMAD according to non-enhanced CT has become a key issue.

Some studies[5,7] have mentioned that an enlarged SMA diameter and/or perivascular exudation on non-enhanced CT may be an indication for SISMAD. For an enlarged SMA, the problem is as follows: (1) how large does the SMA diameter need to be to consider the possibility of SISMAD; (2) because of the differences in the dissection location, entry sites, false lumen, and dissection length, which parts of the SMA diameter should be focused on, the initial part (SMA root) or the other part (SMA trunk)? (3) how about the sensitivity and specificity of the aforementioned parameters? Only a small number of studies involving very few patients have measured the SMA diameter.[4,8] Kim et al[8]measured the maximum diameter of the SMA in 22 SISMAD patients with partial or complete thrombosis of the false lumen and showed that the mean value was 11.6 mm. Yan et al[4] used non-enhanced CT to measure the SMA diameter of a few patients and found mean values in the SISMAD and control groups were 11.69±1.26 mm and 7.10±0.97 mm, respectively. Therefore, reports about misdiagnosis or missed SISMAD are not rare because of insufficient awareness.[6,9] Zhao et al[9] studied 11 SISMAD patients who were admitted to the ED and found misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis in 7 (63.6%) cases. Yan et al[4] mentioned that 3 in 20 abdominal pain patients with an increased SMA diameter on non-enhanced CT failed to detect any abnormalities, and an additional CECT the next day diagnosed SISMAD.

Although reports of SISMAD have increased recently, the role of non-enhanced CT remains to be fully investigated in a large cohort of patients with SISMAD.[5] In this study, we attempted to explore the role of non-enhanced CT in the early diagnosis of SISMAD by comparing SISMAD patients with the matched sex and age abdominal pain non-SISMAD patients to find out the diagnostic efficiency of maximum SMA diameter, perivascular exudation, and the ratio of the SMA diameter to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) diameter (SMA/SMV) on non-enhanced CT.

METHODS

Study population

The present study was a retrospective review of all abdominal pain patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of SISMAD according to the findings of CECT, CTA, or digital subtraction angiography performed between December 2013 and June 2021. Meanwhile, to take SISMAD patients as references, the matched sex and age abdominal pain non-SISMAD patients at 1:2 (1 case: 2 controls) were collected in reverse chronological order to form the control group. All patients in the control group were performed with intravenous contrast. Patient demographics, the duration from symptom onset to admission, clinical manifestations, and comorbidities were independently searched by two authors. The diagnosis of SISMAD was confirmed by one of the following signs: (1) intimal flap and false lumen; and (2) crescent-shaped area along the wall of the SMA without contrast enhancement, indicating a thrombosed false lumen.[1,10] The inclusion criteria were non-enhanced CT, CECT, CTA, or digital subtraction angiography imaging data. The exclusion criteria were: (1) absence of non-enhanced CT data; (2) vague SMA or SMV on non-enhanced CT; (3) absence of abdominal pain; (4) recent abdominal trauma; or (5) concomitant aortic dissection.

SMA and its related index evaluation and data measurement

In our study, SMA and its surrounding data were collected through non-enhanced CT. Non-enhanced CT was performed with a section thickness of 1.25-5.00 mm. The diameters of the SMA and SMV in the SISMAD and control groups were measured on original axial non-enhanced CT views. The SMA diameter was measured in two parts: (1) SMA root (from the ostium of the SMA to the bottom of the portal venous confluence) and (2) SMA trunk (from the bottom of portal venous confluence to the origin of the ileocolic branch). When measuring the diameter of the SMA trunk, the diameter of the satellite SMV on the same plane was also measured. All images were jointly reviewed by two doctors-in-charge who were excellent in abdominal radiology. The measurements were repeated twice and averaged. Any discrepancies between the evaluation results were resolved by discussion.

Definitions

The diameter of the SMA root was defined as the maximum diameter of the SMA root, and the diameter of the SMA trunk was defined as the maximum diameter of the SMA trunk. The SMV diameter was defined as the diameter of the satellite SMV, which was on the same plane as the maximum diameter of the SMA trunk. SMA/SMV was the ratio of the SMA diameter to the SMV diameter and was calculated as the diameter of the SMA trunk/the SMV diameter. The maximum SMA diameter was defined as the larger diameter of the SMA root or SMA trunk.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 and MedCalc version 20.0. Numerical data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and categorical data were expressed as n (%). Student's t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Chi-square test were used to compare the differences between the SISMAD and control groups. MedCalc was used to produce the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Combined parameters of the ROC curve were performed by: (1) calculating the value of the combined parameters by binary logistics regression, which was analyzed by SPSS; (2) putting the value of the combined parameters as a whole under the ROC curve. A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Basic information and laboratory data

A total of 291 abdominal pain patients, including 97 (33.3%) patients with SISMAD and 194 (66.7%) patients in the control group, were included in the present study. The age of the patients was 52.03±7.39 years (range 37-77 years), and 89.7% of them were male. The two groups differed regarding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of malignancy or digestive system malignancy (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of basic information of the enrolled patients

| Variables | Total patients (n=291) | SISMAD group (n=97) | Control group (n=194) | t/χ2/Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 52.03±7.39 | 52.03±7.42 | 52.03±7.40 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Male | 261 (89.7) | 97 (89.7) | 174 (89.7) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 78 (26.8) | 37 (38.1) | 41 (21.1) | 9.537 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (7.6) | 0 (0) | 22 (14.7) | 11.900 | 0.001 |

| Liver-relative disease | 45 (15.5) | 13 (28.9) | 32 (16.5) | 0.473 | 0.492 |

| Malignancy | 47 (16.2) | 5 (5.2) | 42 (21.6) | 12.992 | <0.001 |

| Digestive system malignancy | 37 (12.7) | 1 (1.0) | 36 (18.6) | 17.897 | <0.001 |

| Heart disease | 9 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 9 (4.6) | 3.225 | 0.073 |

| Arrhythmia | 9 (3.1) | 4 (4.1) | 5 (2.6) | 0.129 | 0.719 |

| Duration of abdominal pain, d | 1.0 (0.4-3.0) | 1.0 (0.3-3.0) | 0.5 (1.0-3.0) | -1.176 | 0.239 |

Numerical data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation, n (%), or median (interquartile range). SISMAD: spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection.

The findings on non-enhanced CT

Compared with non-SISMAD patients, SISMAD patients had larger maximum SMA diameter, perivascular exudation, SMA/SMV on non-enhanced CT (all P<0.05, Table 2). Among the 97 SISMAD patients, 66 patients had a non-enhanced CT before undergoing CECT or CTA, but only 22 (33.3%) patients had changes in SMA on the non-enhanced CT report.

Table 2. Comparison of SMA and its related indices

| Variables | Total patients (n=291) | SISMAD group (n=97) | Control group (n=194) | t/χ2/Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of SMA root, mm | 9.43±1.41 | 10.25±1.56 | 9.02±1.13 | 6.897 | <0.001 |

| Diameter of SMA trunk, mm | 8.70 (7.72-10.28) | 11.18 (10.15-12.13) | 8.00 (7.40-8.70) | -13.217 | <0.001 |

| SMV diameter, mm | 11.65±1.68 | 11.36±1.44 | 11.80±1.78 | -2.128 | 0.034 |

| SMA/SMV | 0.75 (0.65-0.90) | 1.00 (0.89-1.10) | 0.69 (0.61-0.75) | -12.671 | <0.001 |

| Maximum SMA diameter, mm | 9.60 (8.70-10.89) | 11.37 (10.39-12.38) | 9.07 (8.33-9.69) | -11.854 | <0.001 |

| Location of maximum SMA diameter (SMA trunk) | 84 (28.9) | 72 (74.2) | 12 (6.2) | 145.801 | <0.001 |

| Perivascular exudation | 114 (39.2) | 59 (60.8) | 55 (48.2) | 28.620 | <0.001 |

Numerical data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation, n (%), or median (interquartile range). SMA: superior mesenteric artery; SISMAD: spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection; SMV: superior mesenteric vein; SMA/SMV: the ratio of the SMA diameter to the SMV diameter.

ROC curves

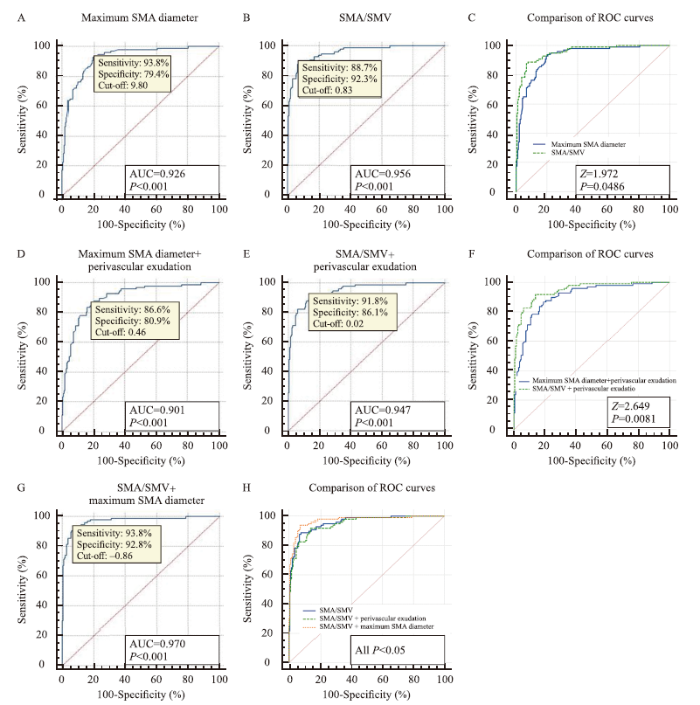

The ROC curves showed that for the maximum SMA diameter parameter, the area under the curve (AUC), cut-off, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.926, 9.80, 93.8%, and 79.4%, respectively (Figure 1A), and when the cut-off value was 11.9 mm, the sensitivity and specificity were 34% and 98%, respectively. For SMA/SMV, its AUC, cut-off, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.956, 0.83, 88.7%, and 92.3%, respectively (Figure 1B), and when the cut-off value was 0.92, the sensitivity and specificity were 65% and 98%, respectively. Compared with the two aforementioned parameters, the diagnostic efficiency of SMA/SMV was better than that of the maximum SMA diameter (P<0.05, Figure 1C). For the combined parameters of maximum SMA diameter and perivascular exudation, the AUC, cut-off, sensitivity, and specificity were 0.901, 0.46, 86.6%, and 80.9%, respectively (Figure 1D). For the combined parameters of SMA/SMV and perivascular exudation, the AUC, cut-off, sensitivity and specificity were 0.947, 0.02, 91.8%, and 86.1%, respectively (Figure 1E). Compared with the two parameters mentioned above, the diagnostic efficiency of SMA/SMV and perivascular exudation was better than that of the maximum SMA diameter and perivascular exudation (P<0.05, Figure 1F). The combined parameters of SMA/SMV and maximum SMA diameter had the best diagnostic efficiency (AUC=0.970), and when the cut-off value was -0.86, the sensitivity and specificity were 93.8% and 92.8%, respectively (P<0.05, Figures 1 G and H).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ROC curves. ROC curves showing the AUC, cut-off, sensitivity and specificity of the maximum SMA diameter (A), SMA/SMV (B), combined parameters of maximum SMA diameter and perivascular exudation (D), SMA/SMV and perivascular exudation (E), and SMA/SMV and maximum SMA diameter (G). In the diagnostic efficiency aspect, SMA/SMV was better than the maximum SMA diameter (P<0.001, C). The combined parameters of SMA/SMV and perivascular exudation were better than the maximum SMA diameter and perivascular exudation (P<0.05, F); the combined parameters of SMA/SMV and maximum SMA diameter were the best (P<0.05, H). If the value of the maximum SMA diameter was X (mm), SMA/SMV was Y, and perivascular exudation was Z (if have, Z=1; if not, Z=2), then the value of X+Z = -17.418+1.602*X+1.135*Z; the value of Y+Z = -16.718+19.016*Y+0.928*Z; and the value of X+Y = -23.742+1.012*X +15.624*Y. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; AUC: area under the curve; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; SMA/SMV: the ratio of the SMA diameter to the superior mesenteric vein diameter.

DISCUSSION

SISMAD is considered to be an uncommon vascular disease, presenting with abdominal pain (a very common complaint in emergency settings) as the main symptom.[1,5] However, following improvements in diagnostic radiological practices and the wider availability of high-quality CTA and CECT in recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in reports of this disease.[1,2,11-13] Although there are some reports on SISMAD, most of them focus on its treatment, follow-up, and clinical characteristics.[1,2,10,12,14-17] There have been very few studies on the use of imaging in the early diagnosis of this disease, and the characteristics of non-enhanced CT have not been investigated in detail for doctors, especially emergency doctors.[5,7,18] In this study, we compared SISMAD patients with the matched sex and age abdominal pain non-SISMAD patients and found that not only the maximum SMA diameter but also the SMA/SMV may play an important role in the early diagnosis of SISMAD. Although there are studies focusing on the diameter of the aortic dissection,[19,20] the present study focused on SMA/SMV parameters on non-enhanced CT in patients with SISMAD, and this was the largest single-center cohort in which the maximum SMA diameter and SMV diameter on non-enhanced CT were measured.

SISMAD is a rare disease that is more prevalent in men in their fifties.[6,11,12] For SISMAD patients, abdominal pain is the most common symptom, accounting for 72%-100%.[1,3,5,6,8,11,13,15] Although a small number of SISMAD patients are diagnosed by ultrasound, its use is limited because it is affected by intestinal gas and obesity.[6,21] CECT is the most appropriate examination for abdominal pain patients in many settings.[22] Non-enhanced CT may be performed in several situations where contrast medium is contraindicated and hospital medical resources are limited.[4,5] Hence, the role of non-enhanced CT is often underestimated in SISMAD patients for the following reasons: (1) the rarity of this condition, and the findings of non-enhanced CT often neglected by doctors and radiologists because of insufficient awareness; (2) the positive findings on non-enhanced CT were low, which were judged by perivascular exudation and/or an enlarged SMA diameter. In our study, only one in three SISMAD patients had changes in the SMA on the CT report. Owing to the lack of reliable clinical signs and laboratory findings, CECT and CTA are the main clinical methods for diagnosing SISMAD.[11,14,17] In order to improve the early diagnostic rate and avoid overdiagnosis for abdominal pain patients who have already undergone non-enhanced CT, it is a clinically urgent problem that which patients should be further performed with CTA or CECT to diagnose or rule out SISMAD.

The previous studies on non-enhanced CT show that perivascular exudation and/or an enlarged SMA diameter, although nonspecific, may be an indication for SISMAD.[5,7] Perivascular exudation can be caused by digestive system malignancy, inflammation, or other vascular disorders.[23] Suzuki et al[7] showed that perivascular exudation was found in five of six SISMAD cases and was considered as the key to the diagnosis when no definite findings were evident. Tan et al[5]studied 79 SISMAD patients from February 2015 to February 2018 and found perivascular exudation in 34 cases. They thought that perivascular exudation might be a marker for SISMAD, particularly in the emergency setting, and it indicated a need for further examination. An enlarged SMA diameter consists of a true lumen, a false lumen, and an intimal flap, which could not be clearly observed on non-enhanced CT. The enlarged diameter is not very obvious except for aneurysms. Only a small number of studies involving a few patients have included measurements of the SMA diameter.[4,8] Hence, it is a question that how large the SMA diameter needs to be before considering SISMAD.

In our study, the maximum SMA diameter was similar to or even larger than the satellite SMV diameter. The diagnostic efficiency of SMA/SMV was better than that of the maximum SMA diameter. Similarly, the diagnostic efficiency of the combined parameters of SMA/SMV and perivascular exudation was better than that of the maximum SMA diameter or perivascular exudation alone. Moreover, because of the relatively fixed position of the SMA and SMV, the SMA/SMV was also relatively easy to acquire. Hence, we thought that the SMA/SMV might become a vital reference index in the early diagnosis of SISMAD in the future. Of course, when we combined the parameters of maximum SMA diameter and SMA/SMV, the combined parameters were more helpful for the diagnosis of SISMAD.

CONCLUSIONS

SMA/SMV on non-enhanced CT has an excellent AUC, sensitivity, and specificity in the early diagnosis of SISMAD. For acute abdominal pain in men in their fifties, we highly recommend measuring SMA/SMV and/or the maximum SMA diameter on non-enhanced CT before CECT or CTA to diagnose or rule out SISMAD. If the maximum SMA diameter is similar to or larger than that of the SMV, then a diagnosis of SISMAD should be considered, and further CECT or CTA should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. In short, SMA/SMV on non-enhanced CT may be a potential marker for SISMAD, particularly in the emergency setting, and it indicates a requirement for CECT or CTA examination.

Funding: The study was supported by Clinical Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Medical Association (2021ZYC-A73).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (KY2021-R119). Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors: All authors made an individual contribution to the writing of the article, including design, literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, statistical analysis, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing.

Reference

Safety and efficacy of conservative, endovascular bare stent and endovascular coil assisting bare stent treatments for patients diagnosed with spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection

Management of symptomatic spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: a single centre experience with mid term follow up

DOI:10.1016/j.ejvs.2020.08.010 URL [Cited within: 3]

Mid-term results of endovascular treatment for spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery

DOI:10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.11.013 URL [Cited within: 2]

Multidetector computed tomography in the diagnosis of spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: changes in diameter on non-enhanced scan and stent treatment follow-up

DOI:10.1177/0300060519860328 URL [Cited within: 7]

Clinical implications of perivascular fat stranding surrounding spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection on computed tomography

Diagnosis and management of isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis

DOI:10.4070/kcj.2018.0429 URL [Cited within: 5]

Isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery: CT findings in six cases

PMID:15290937

[Cited within: 4]

Dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) not associated with aortic dissection is rare. The purpose of this study is to describe the computed tomographic (CT) findings of this condition. We studied the CT findings of six patients with isolated dissection of the SMA. CT demonstrated thrombosis of the false lumen or intramural hematoma (n = 4) and/or intimal flap (n = 4) in all six patients. Other CT findings were enlarged diameter of the SMA (n = 5), increased attenuation of the fat around the SMA (n = 5), and hematoma in the mesentery with hemorrhagic ascites (n = 1). CT is useful for the diagnosis of isolated dissection of the SMA, and increased attenuation of the fat around the artery is considered the key to the diagnosis when no definite findings are evident.

Clinical and radiologic course of symptomatic spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery treated with conservative management

DOI:10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.112 URL [Cited within: 4]

Diagnosis and treatment of acute spontaneous isolated visceral artery dissection abdominal pain in emergency department

Conservative management of spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery

Diagnostic imaging findings and endovascular treatment of patients presented with abdominal pain caused by spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection

Clinical and angiographic follow-up of spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection

Spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: systematic review and meta-analysis

DOI:10.1177/1708538118818625

PMID:30621507

[Cited within: 2]

Spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection (SISMAD) is a rare disease with an incidence of 0.06%. The purpose of the meta-analysis was to identify the outcomes associated with the various treatment options in the management of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SISMAD.Eligible studies were selected by searching PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library. Endpoints were outcome of asymptomatic patients treated conservatively, resolution of symptoms according to the treatment approach, rate of symptomatic patients switched from conservative to the endovascular and/or open repair, characteristics of the dissected lesion, and findings regarding the remodeling of superior mesenteric artery.We identified 30 studies including 729 patients. Among them, 608 (83.4%) were symptomatic and were managed with conservative (438/72%), and/or endovascular (139/22.8%) and/or open treatment (31/5%). The remaining were asymptomatic and they were treated solely conservatively. A high rate of resolution of symptoms (92.8%) was noted for patients treated conservatively. Conversion from conservative treatment to either endovascular or open procedure was required in 12.3% and 4.4%, respectively. Resolution of symptoms was observed in 100% for those treated with open procedure and 88.8% for those treated endovascularly. The pooled rate of bowel ischemia in patients treated conservatively was 3.75% (95% confidence interval = 1.15-7.27). Complete remodeling was achieved in 32% and partial in 26% of those who were treated conservatively.The majority of symptomatic patients with SISAMD were treated conservatively and showed an uncomplicated course and only a small percentage required conversion to endovascular or open repair. This might highlight the benign course of the disease.

Isolated spontaneous superior mesenteric artery dissection: a rare cause of unexplained abdominal pain

DOI:10.1002/aid2.13193 URL [Cited within: 2]

Natural history of spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection derived from follow-up after conservative treatment

DOI:10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.052 URL [Cited within: 1]

Management strategy for spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery based on morphologic classification

DOI:10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.014 URL

Two cases of spontaneous isolated dissection of superior mesenteric artery in one night: report of a (noninvasive) double challenge

Computed tomography imaging features and classification of isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery

DOI:10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.04.035 URL [Cited within: 1]

The ratio between descending aorta and ascending aorta diameter for rapid diagnosis of Stanford type B aortic dissection

Ascending aortic dilatation rate after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic stenosis: a multidetector computed tomography follow-up study

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2019.04.001 URL [Cited within: 1]

Diagnostic value of color Doppler sonography for spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection

Factors associated with refractory pain in emergency patients admitted to emergency general surgery

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2021.01.002 URL [Cited within: 1]

Segmental misty mesentery: analysis of CT features and primary causes

DOI:10.1148/radiol.2261011547 URL [Cited within: 1]