Congenital coronary sinus (CS) fistula is a rare form of cardiac abnormality. The fistula forms an abnormal communication between the cardiac chambers and the coronary arteries. The most common form of fistula arises from the right coronary arteries while the left ventricular and CS fistula is rare. Coronary slow-flow phenomenon (CSFP) is defined as a delayed opacification of distal vessels without any epicardial disease.[1] The pathogenesis of CSFP is not well described in the literature.[2]

In the majority of cases, the left ventricular and CS fistula remains silent and can only be diagnosed incidentally.[3] Congenital fistula between the left ventricle and CS was firstly reported in the 1980s by necropsy.[4] Dilatation of the CS is usually caused by increased blood flow and may be due to the result of coronary arteriovenous fistula.[5]

We are presenting a rare form of congenital left ventricular and CS fistula in an elderly patient who presented with the complaint of chest pain. The clinical presentation, imaging studies, and the treatment were presented along with the discussion.

A 78-year-old male was referred to our cardiology department with a complaint of repeated chest tightness from a local hospital. The patient was normotensive, normoglycemic and previously healthy without any history of ischemic heart disease. The echocardiography was done and it showed mild tricuspid valve regurgitation and left atrial enlargement.

Coronary angiography (CAG) was performed to evaluate the aetiology. CAG showed no atherosclerotic plaque or coronary artery obstruction but it only indicated CSFP. To find out the heart function or any septal defect, the patient underwent left ventriculography.

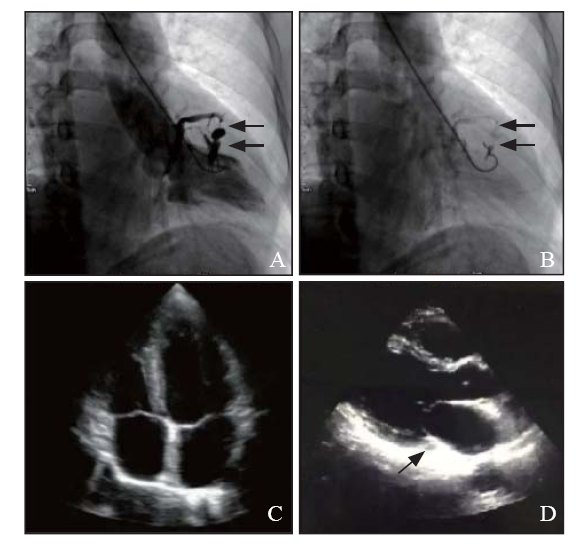

During the first high-pressure injection, the pigtail catheter was recoiled and trapped by trabecular muscles, as a result, an intramural hematoma was formed on the left ventricular wall and several vessel channels were seen as a fistula which rapidly flew into the CS (Figure 1 A). Besides, the size and systolic function of the left ventricle were normal and there was no mitral valve regurgitation. Both systolic and diastolic pressures of the left ventricle were normal. To estimate the unexpected hematoma and fistula, another injection was made at the same position on the left ventricular wall with a lower pressure. The re-ventriculography showed that left ventricle and CS had been connected with the fistula and contrast remained on the myocardium (Figure 1 B). Emergency echocardiography was performed and it showed no tamponade or any other complications (Figures 1 C and D). Holter monitor was placed for 48 hours to evaluate the complication and hemodynamic status of the patient. A 40 mg isosorbide mononitrate sustained release tablets were provided to the patient to improve chest tightness and CSFP on the second day. In view of normal heart function, no surgery was implemented on this patient. The patient was discharged on the third day and advised for a one-year follow up.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cardiac catheterization of left ventriculography and emergency echocardiography. A: intramural hematoma formed on the left ventricular wall caused by left ventriculography and several channels connected with coronary sinus (CS) (black arrows); B: re-ventriculography with lower pressure on the same position showed the potential fistula from left ventricle to CS (black arrows); C: 4-chamber echocardiography indicated no complication; D: no enlarged CS (black arrows) was found on the long axis of echocardiography.

The left ventricle to CS fistula is a rare anomaly. During embryological development, the CS arises from the sinus venosus, thus it must not have any communication to the left ventricle. The common etiologies to acquire the fistula are myocardial infarction, catheter ablation, and mitral valve replacement. Small-sized coronary fistula remains silent without any significant effects on the myocardial blood flow. The persistent fistula may cause hemodynamic instability to the myocardium and become symptomatic in about 63% of the adult population.[6] Symptoms may include ischemic myocardium, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction, thromboembolism of the fistula, endocarditis, and cardiomyopathy.[7]

Almost all the cardiac fistulas including the left ventriclar and CS fistula require surgical closure. Percutaneous closure aided with three-dimensional computed tomography is a well described strategy in the catheterization lab with a low post operative mortality and morbidity.[8]

There is no well explained literature, which is available to explain the CSFP related to the left ventricular and CS fistula. The left ventricle is a high-pressure chamber as compared to the CS, so it may be possible that during the systole, the blood flows from the left ventricle to the CS, which may cause CSFP. In our patient, it might be possible that the slow coronary flow rate was associated with the fistula. However, it is uncertain to draw any conclusion rather it requires further investigations to confirm because it is a very rare anomaly.

In this case, we figured out that the CSFP was responsible for causing the symptoms and it may be due to the persistent congenital ventricular-coronary sinus fistula. This case highlights a rare phenomenon of congenital left ventricular and CS fistula in an elderly patient. The patient was previously healthy and asymptomatic which is a rare presentation because patients with congenital fistulas usually present to the clinic in their early life. Therefore, in elderly patients, the CSFP may be due to the presence of a left ventricular and CS fistula. We suggest that such patients should be evaluated for fistula and interventional cardiologists need to be cautious to avoid any complications.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interests: None.

Contributors: QN made the manuscript, HS collected data and revised the paper, ALH provided Echo images, HCZ and JZ carried out the operation, and WX finally checked the paper and gave advice about this case.

Reference

Assessment of risk factors and left ventricular function in patients with slow coronary flow

DOI:10.1007/s00380-014-0606-4 URL [Cited within: 1]

Coronary slow-flow phenomenon as an underrecognized and treatable source of chest pain: case series and literature review

Coronary-cameral fistula: obtuse marginal to left ventricle via anterolateral papillary muscle

Congenital fistula between left ventricle and coronary sinus

PMID:7459159

[Cited within: 1]

The occurrence of a congenital fistula between the left ventricle and the coronary sinus has not previously been reported. A patient with this rare anomaly is described in whom the diagnosis was established during life and confirmed at operation and necropsy.

Aortic root replacement for a TAVR-induced aortic root-to-right ventricular fistula

DOI:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.01.067 URL [Cited within: 1]

Congenital coronary artery fistulae: a rare cause of heart failure in adults

DOI:10.1186/1749-8090-9-87 URL [Cited within: 1]

Coronary artery-left ventricular fistula and takotsubo cardiomyopathy—an association or an incidental finding? A case report

DOI:10.12659/AJCR.908836 URL [Cited within: 1]

Congenital left ventricle-to-coronary sinus fistula: a rare isolated anomaly of the coronary sinus

DOI:10.1016/j.case.2017.04.007 URL [Cited within: 1]