INTRODUCTION

Workplace violence refers to a physical and/or psychological attack to which a person is exposed while working. This may be verbal or physical (armed or unarmed), resulting in injury or even death.[1] In addition, employees’ reduced motivation caused by such an attack and their lack of security may reduce their work efficiency or cause them to resign from their job.[2]

The highest rate of exposure to workplace violence is seen in healthcare institutions (25%).[1] Studies have also shown that most of the violence witnessed in the health sector is either unreported or overlooked. In particular, the employees of emergency services, psychiatric services, and the services where dementia patients are examined face the highest level of violence. Among health workers, doctors and nurses constitute the group that is most exposed to violence.[1,3] The overcrowded and noisy environment of emergency services, long waiting time, presence of very anxious patient relatives, sudden onset and severe complaints of emergency patients, and physicians not being able to fully attend to the patients’ needs create tension, which is reflected as violence on doctors and nurses in the vicinity.[4] Emergency service employees are more likely to be exposed to violence than other healthcare workers.[5] These acts of violence are mostly verbal, and they are committed by the relatives of patients in the waiting room.[1]

Many studies in the literature have investigated violence toward healthcare workers.[1,2,6] In most of these studies, the data were collected by administering questionnaires to doctors and nurses who had been exposed to violence. In contrast, in the current study, we aim to determine the characteristics and causes of violence toward emergency physicians by interviewing not only the physicians exposed to such behavior but also the patients and their relatives who had displayed violent behavior.

METHODS

Study setting

This prospective study was conducted in the adult emergency service of a tertiary hospital. Our emergency department (ED) provides services to an average of 25,000 patients monthly, with four physicians working at each shift.

Study protocol

The incidents of violence toward emergency physicians were examined from June 2018 to May 2019. The study was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, when an emergency physician was exposed to a violent act, a third party that was not involved in violence (doctor, nurse, or social services expert) asked the patients and their relatives to attend an interview after the situation was under control and the perpetrator had calmed down. This mediator interviewed the patient, his/her relatives, and the physician exposed to violence using questions prepared by the researchers.

The questions for the patients and their relatives responsible for the violent act were as follows: (1) what was your reason for presenting to the emergency service?; and (2) what was the cause of the problem with the emergency physician? The physicians exposed to violent behavior were directed the following questions: (1) what was the patient’s medical complaint?; and (2) what was your diagnosis? Then, the responses of the patients/patient relatives and physicians, type of violence, place and time of violence, characteristics of the perpetrator (e.g., gender and place of residence), medical outcome, duration of emergency service stay, and the patients’ social health insurance were recorded in the prepared form. In our study, we included verbal and physical violent acts, but excluded sexual assault incidents. Verbal threatening, yelling, and swearing were considered as verbal violence, while pushing, kicking, scratching, punching, or pulling was evaluated as physical violence.

It was determined that the patients or relatives gave 19 different responses to the question of why they had exhibited violence toward an emergency physician. These responses were analyzed by three physicians that were not a part of the study and also not a party to the violent act (one psychiatrist and two emergency medicine specialists). As a result of this analysis, the responses given were generalized, and six different causes of violence were identified: (1) dissatisfaction with the examination or treatment method and making his/her own treatment recommendation; (2) thinking that the patient was not given enough attention by the physician, nurse, or staff; (3) long waiting time in the emergency service, (4) extremely anxious patient or patient relatives; (5) problems related to the infrastructure of the hospital; and (6) non-health-related and unethical requests of the patients.

Throughout the study, non-physician emergency service workers (nurses, security guards, technicians) were also subjected to many violent acts. However, since many of these incidents were not reported or recorded, they were not included in the study. In addition, the cases of violence due to excessive alcohol consumption or drug abuse were excluded in order to reach more precise conclusions about the causes of violence through patients who were conscious and able to communicate. Furthermore, we excluded the patients who continued to be violent, who left the emergency service immediately after the incident, and who did not want to participate in the study. In our country, in addition to private insurance schemes, there are two basic health state insurance systems. The first is the green card system, in which all healthcare costs are covered by the state without any limitation. Green cards are issued for Turkish citizens with a total income level less than one-third of the minimum wage. The second is the Social Security Institution (SSI) insurance, in which the state contributes to a percentage of healthcare costs. This is provided for civil servants, manual laborers, and tradespeople.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the study were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 17). The descriptive statistics were given as frequency, percentage, and mean±standard deviation values. Graphs were constructed to present some of the categorical variables.

RESULTS

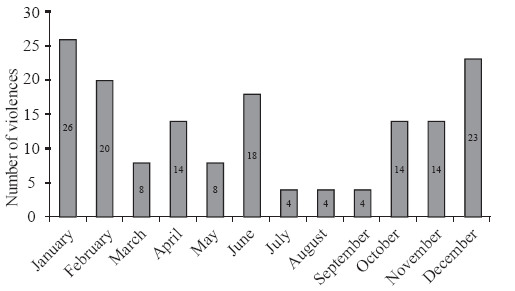

During the one-year study, there were 157 violent acts toward emergency physicians, and 81.5% were verbal. The majority were committed by males (77.1%) and patient relatives (68.8%). The age of the perpetrators was 31.9±10.2 years, with 91.1% being under 45 years. Female physicians were exposed to violence in 59 violence cases and male physicians in 98. Almost half of the violent acts (49.0%) took place from 04:00 p.m. to 00:00 a.m., followed by 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. (30.6%). Violence toward physicians was mostly seen within the first 15 minutes of presentation to the emergency service (60.5%), while 84.7% occurred within the first hour. Of the cases involving violence, 77.1% were discharged after the emergency intervention, 20.4% were hospitalized, and 2.5% died in the ED. Of the 29 patients who displayed physical violence, 23 (79.3%) were discharged and six were hospitalized. The waiting time in the emergency service was 98.7±88.9 minutes, and 75.2% of the patients waited for less than two hours. Concerning health insurance, 79.6% of the patients who were violent toward emergency physicians were covered by the health insurance provided by SSI and the remainder held a Turkish green card. In terms of the place of residence, 61.8% of the cases lived in urban areas, and the remainder in rural areas (Table 1). In terms of the time of a year, the incidents of violence mostly occurred in January (16.6%), December (14.7%), and February (12.7%) (Figure 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of violence (n=157)

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Violence type | ||

| Verbal | 128 | 81.5 |

| Physical | 29 | 18.5 |

| Perpetrator | ||

| Patient | 49 | 31.2 |

| Relatives | 108 | 68.8 |

| Gender of perpetrator | ||

| Female | 36 | 22.9 |

| Male | 121 | 77.1 |

| Age of perpetrator (year) | ||

| <45 | 143 | 91.1 |

| ≥45 | 14 | 8.9 |

| Gender of physician | ||

| Female | 59 | 37.6 |

| Male | 98 | 62.4 |

| Time of violence | ||

| 00:00-08:00 | 32 | 20.4 |

| 08:00-16:00 | 48 | 30.6 |

| 16:00-00:00 | 77 | 49.0 |

| Door to violence time (minutes) | ||

| 0-15 | 95 | 60.5 |

| ≥15-60 | 38 | 24.2 |

| ≥60 | 24 | 15.3 |

| Waiting time (minutes) | ||

| 0-30 | 40 | 25.5 |

| ≥30-120 | 78 | 49.7 |

| ≥120 | 39 | 24.8 |

| Outcome of patient | ||

| Discharged | 121 | 77.1 |

| Hospitalized | 32 | 20.4 |

| Death | 4 | 2.5 |

| Health insurance of patient | ||

| Social Security Institution | 125 | 79.6 |

| Free health insurance | 32 | 20.4 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 97 | 61.8 |

| Rural | 60 | 38.2 |

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of violence by months.

The reason for the violent behavior was mostly associated with the patients’ or their relatives’ dissatisfaction with the method of treatment or examination and making their own treatment recommendations (n=60), followed by the presence of extremely anxious patients or patient relatives (n=26), problems related to the infrastructure of hospital (n=20), thinking that the patient was not given enough attention by physician, nurse, or staff (n=18), long waiting time in the emergency room (n=18), and non-health-related and unethical requests of the patients (n=15). Among the reasons for emergency service presentation, falls came first (n=36, 22.9%), followed by abdominal pain (n=27, 17.2%), traffic accidents (n=25, 15.9%), sore throat (n=18, 11.5%), syncope (n=11, 7.0%), dyspnea (n=9, 5.7%), chest pain (n=9, 5.7%), and other complaints (n=22, 14.0%).

DISCUSSION

Violence toward healthcare workers has become an increasingly serious public health problem worldwide.[7] The gravity of this issue was evidenced by a previous study reporting that 97% and 92% of emergency service workers were exposed to verbal and physical violence, respectively, at least once in their lives. It has been repeatedly found that these violent incidents can have serious consequences, including death.[8,9]

The causes of violence are multifaceted. From the point of physicians, burnout syndrome, feeling inadequate at their jobs, and treating patients as objects will cause communication problems with patients and their relatives, leading to violence. Furthermore, the infrastructure problems of hospitals, such as limited staff and security, overcrowded nature of emergency services, long waiting time, and violation of privacy can be considered as systemic problems.

Patients being under the effect of alcohol or drugs, personal armament, gang violence, low socio-economic level, and the feeling that patients are kept waiting in the emergency service for a long time and not receiving enough attention are other important factors that play a role in violent acts in the health field.[10,11] In Western societies, being under the influence of alcohol and drugs has an important share in the violence that occurs in the emergency service,[9,12] while in a study conducted in Pakistan, the lack of education, overcrowded emergency services, and insufficient security personnel are reported to be the most common causes of violence.[4] In another study, factors, such as long waiting time, dissatisfaction with the treatment, and disagreement with physicians were the main reasons identified.[13] In the current study, the reasons for the violent behavior displayed against emergency physicians were: the dissatisfaction of the patients or their relatives with the examination or treatment method, their feelings of extreme anxiety, systemic problems related to the hospital infrastructure, thinking that the patients were not given enough attention, long waiting time, and non-health-related and unethical demands of the patients or their relatives. In Turkey, patients and their relatives usually present to the ED with the prejudice that emergency physicians are novices and inadequate. Thus, they try to guide the emergency physician during the examination and treatment process in accordance with their level of knowledge and culture. This may be the reason why dissatisfaction with treatment was the most common reason behind the violent acts in this study. Because of the cultural and religious characteristics of the place where we conducted the study, violence due to alcohol and drug use was low. Considering the rarity of these cases, we deliberately excluded these incidents from the current study.

Violence toward emergency service workers is mostly verbal, and physical violence is less frequently seen. However, many emergency physicians report to have witnessed physical violence toward themselves or another emergency worker throughout their careers. In addition, it has been found that poor or no response to verbal violence can lead to physical violence. Here, it is important to consider that individuals exposed to verbal violence are significantly affected in psychological terms, and they need as much support as in victims of physical violence.[3,14,15] In a study by Kowalenko et al,[14] 74.9% and 28.1% of the physicians reported verbal and physical violence, respectively. In another study, 76.2% of the physicians described verbal violence and 24.1% described physical violence.[7] In the current study, 81.5% of the violent incidents were verbal and 18.5% were physical. Studies in the literature are generally in the form of questionnaires, asking the physicians about the violence to which they have been exposed. We expect to have achieved more accurate results since the data were obtained from the interviews with the perpetrators and victims of emergency service violence immediately after the act had taken place.

In this study, the most common reasons for the patients’ presentation to the ED were falls, abdominal pain, traffic accidents, and sore throat. Of the cases investigated, 77.1% were discharged without hospitalization, and 20.4% were hospitalized. In studies revealing different patient profiles, the rate of discharge from hospital was found to be 45%[11] and 35.3%.[16] Trauma cases have the highest mortality after cardiovascular diseases and cancer,[17] and emergency services play an important role in the management of fatal trauma cases, which is confirmed by the majority of our violence cases being trauma-related. However, the majority of our patients being discharged and 15.5% having non-urgent complaints such as sore throat indicate that most cases that led to violence were not life-threatening or did not require hospitalization.

We determined that violence was mostly perpetrated by young male patients and patient relatives. A patient relative can be a parent, blood relation, or friend that accompanies the patient to the emergency service. In some cases, there may be more than one person that wants to help the patient. This situation not only increases the overcrowded nature of the emergency service but also often leads to an increased rate of violent incidents toward healthcare workers.[4] Unlike our results, James et al[18] reported that the majority of violent incidents (88.2%) were initiated by the patient and only 11.8% by a patient companion. In another study conducted in Turkey, similar to our results, 98% of the people engaging in violence toward physicians were found to be patient relatives, male, and aged 15-30 years.[8] Furthermore, while studies conducted in Western countries reported that female physicians were exposed to more violence, studies in Eastern countries indicated a higher incidence of violence toward male healthcare workers.[1,4] In our study, 62.4% of male doctors were exposed to more violence. We consider this to be related to the sociocultural structure of the study area, where treats women with higher respect. Another reason may be that the number of female physicians working in the emergency service was less than that of male physicians.

Although studies report different results, most violent incidents occur in the afternoon and night shifts. In a study by Kaeser et al,[6] 68% of the violent acts occurred from 02:00 p.m. to 08:00 a.m.[19] In another study, the rate of violent incidents during the night shift (11:00 p.m. to 07:00 a.m.) was 51.8%. In contrast, Ferri et al[1] found that 43% of violence occurred in the morning. In our study, we observed 49.0% of violent behavior during the 04:00 p.m. to 00:00 a.m. period. Since outpatient clinics are closed for the majority of this period, there is an increased demand for emergency services. Similarly, the smaller number of doctors, nurses, and staff working night shifts compared to daytime may cause an increase in violence. In addition, concerning the time of a year, we determined that violence mostly occurred in winter months (December, January, and February). However, we were not able to compare this finding because there were no similar studies in the literature.

The prolonged stay in the ED may also cause violence. Dawson et al[12] reported that the duration of emergency stay in cases of violence was longer than that in normal patients (median, 655.5 minutes vs. 376.0 minutes). In another study, it was found that violent incidents occurred, on average, at the 109th minute of the patients’ presentation to the emergency service, and the mean duration of stay in the emergency service was 302.5 minutes.[16] In our study, 60.5% of violence occurred in the first 15 minutes of emergency presentation, and the average waiting time of our cases in the emergency service was 98.7 minutes. When compared to the literature, the duration of stay in our ED was shorter. This may be due to the fact that our ED provides services to all patients with an open door policy. There are a high number of non-urgent cases that receive basic care such as prescriptions that should be seen in outpatient clinics. We need to specify that the triage has been performed by a nurse in our ED, but no patients are returned by a triage nurse without a doctor examination because of the health policy. The emergency physicians do not oppose this situation and examine all patients to avoid legal transactions.

Mirza et al[4] showed that from the perspective of physicians, a lower level of education (52.5%) and higher social status (41.0%) are factors that might lead to violence. In a study comparing migrants of low-income and high-income countries, it was found that the former had a higher tendency to violence.[6] However, in the current study, unlike the literature, violence was mostly caused by individuals living in urban areas and having middle-upper income levels (covered by SSI insurance).

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was the exclusion of violent incidents involving emergency service employees other than emergency physicians (e.g., nurses, technicians, and security guards). In our experience, the number of violent acts against these staff is actually higher than that of physicians. However, most of these incidents are not reported, and therefore we did not have access to this information and we had to limit our data to emergency physicians.

CONCLUSIONS

More than half of the violent incidents against emergency physicians occur within the first 15 minutes of presentation to the emergency service due to the dissatisfaction of the patients/patient relatives with examination or treatment and their feelings of extreme anxiety. In addition, violent behavior is mostly displayed by males and patient relatives, and during night shifts. In light of these results, our first recommendation is that the hospital management should take sufficient and deterrent measures to ensure the safety of healthcare workers. Secondly, from the moment of entry into the emergency service, regardless of the complaint, appropriate communication should be established between the patients and the physicians, and the patients should be adequately informed about the treatments and interventions to be performed in order to prevent possible acts of violence. Furthermore, problems related to the infrastructure of hospitals, such as the shortage of physicians and other healthcare personnel, should be resolved by the management. For other frequently encountered problems, such as patient requests for unnecessary medical reports, informatory signs explaining that such unethical requests are not granted should be clearly displayed in various parts of the emergency service.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Associate Professor Behice H. Almıs (Psychiatry), Associate Professor Ugur Lök (Emergency Service), and Associate Professor Umut Gülactı (Emergency Service) for their contribution to the interpretation of the participants’ responses.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Adiyaman University (Approval number: 2018/8-9).

Conflicts of interests: We have read and understood the journal’s and ICJME policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Contributors: KT and EY offered the idea and conducted the literature review. KT, MKY, and MKP collected the data together. KT and EY performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. MKP and MKY participated in the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Reference

Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: a cross-sectional study

DOI:10.2147/PRBM.S114870

URL

PMID:27729818

[Cited within: 7]

BACKGROUND: Workplace violence (WPV) against health professionals is a global problem with an increasing incidence. The aims of this study were as follows: 1) to examine the frequency and characteristics of WPV in different settings and professionals of a general hospital and 2) to identify the clinical and organizational factors related to this phenomenon. METHODS: The study was cross-sectional. In a 1-month period, we administered the

Violence toward health workers in Bahrain Defense Force Royal Medical Services’ emergency department

DOI:10.2147/OAEM.S147982

URL

PMID:29184452

[Cited within: 2]

Background: Employees working in emergency departments (EDs) in hospital settings are disproportionately affected by workplace violence as compared to those working in other departments. Such violence results in minor or major injury to these workers. In other cases, it leads to physical disability, reduced job performance, and eventually a nonconducive working environment for these workers. Materials and methods: A cross-sectional exploratory questionnaire was used to collect data used for the examination of the incidents of violence in the workplace. This study was carried out at the ED of the Bahrain Defense Force (BDF) Hospital. Participants for the study were drawn from nurses, support staff, and emergency physicians. Both male and female workers were surveyed. Results: The study included responses from 100 staff in the ED of the BDF Hospital in Bahrain (doctors, nurses, and support personnel). The most experienced type of violence in the workers in the past 12 months in this study was verbal abuse, which was experienced by 78% of the participants, which was followed by physical abuse (11%) and then sexual abuse (3%). Many cases of violence against ED workers occurred during night shifts (53%), while physical abuse was reported to occur during all the shifts; 40% of the staff in the ED of the hospital were not aware of the policies against workplace violence, and 26% of the staff considered leaving their jobs at the hospital. Conclusion: This study reported multiple findings on the number of workplace violence incidents, as well as the characteristics and factors associated with violence exposure in ED staff in Bahrain. The results clearly demonstrate the importance of addressing the issue of workplace violence in EDs in Bahrain and can be used to demonstrate the strong need for interventions.

Assaulted and unheard: violence against healthcare staff

DOI:10.1177/1048291117732301

URL

PMID:28899214

[Cited within: 2]

Healthcare workers regularly face the risk of violent physical, sexual, and verbal assault from their patients. To explore this phenomenon, a collaborative descriptive qualitative study was undertaken by university-affiliated researchers and a union council representing registered practical nurses, personal support workers, and other healthcare staff in Ontario, Canada. A total of fifty-four healthcare workers from diverse communities were consulted about their experiences and ideas. They described violence-related physical, psychological, interpersonal, and financial effects. They put forward such ideas for prevention strategies as increased staffing, enhanced security, personal alarms, building design changes,

Violence and abuse faced by junior physicians in the emergency department from patients and their caretakers: a nationwide study from Pakistan.

[J]

Physical and verbal violence against health care workers

Verbal and non-verbal aggression in a Swiss university emergency room: a descriptive study. Int

[J]

Workplace violence, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health in Chinese doctors: a large cross-sectional study

DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017182

URL

PMID:29222134

[Cited within: 2]

BACKGROUND: Workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare workers is known as violence in healthcare settings and referring to the violent acts that are directed towards doctors, nurses or other healthcare staff at work or on duty. Moreover, WPV can cause a large number of adverse outcomes. However, there is not enough evidence to test the link between exposure to WPV against doctors, psychological stress, sleep quality and health status in China. OBJECTIVES: This study had three objectives: (1) to identify the incidence rate of WPV against doctors under a new classification, (2) to examine the association between exposure to WPV, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health of Chinese doctors and (3) to verify the partial mediating role of psychological stress. DESIGN: A cross-sectional online survey study. SETTING: The survey was conducted among 1740 doctors in tertiary hospitals, 733 in secondary hospital and 139 in primary hospital across 30 provinces of China. PARTICIPANTS: A total of 3016 participants were invited. Ultimately, 2617 doctors completed valid questionnaires. The effective response rate was 86.8%. RESULTS: The results demonstrated that the prevalence rate of exposure to verbal abuse was the highest (76.2%), made difficulties (58.3%), smear reputation (40.8%), mobbing behaviour (40.2%), intimidation behaviour (27.6%), physical violence (24.1%) and sexual harassment (7.8%). Exposure to WPV significantly affected the psychological stress, sleep quality and self-reported health of doctors. Moreover, psychological stress partially mediated the relationship between work-related violence and health damage. CONCLUSION: In China, most doctors have encountered various WPV from patients and their relatives. The prevalence of three new types of WPV have been investigated in our study, which have been rarely mentioned in past research. A safer work environment for Chinese healthcare workers needs to be provided to minimise health threats, which is a top priority for both government and society.

Dangers faced by emergency staff: experience in urban centers in southern Turkey

URL

PMID:19562545

[Cited within: 2]

BACKGROUND: The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence and characteristics of aggression, threat and physical violence directed towards the staff in emergency departments. METHODS: A questionnaire was completed by the emergency staff. The individualized data collected included the pattern and incidence of violence, sex, age, profession, and years of experience of the emergency staff, and the behavioral characteristics of the assailants, together with outcome of incidents. Data regarding incidences occurring between May 1-31, 2006 were abstracted. RESULTS: A total of 109 staff were evaluated. There was a statistically significant relationship between aggression and profession (p=0.000), but no relation was determined with sex, age or years of experience (p values 0.464, 0.692, and 0.298, respectively). The relationship of incidences of threat with sex, age, profession, and experience was insignificant (p values 0.311, 0.278, 0.326, 0.994, respectively). On the other hand, significant relationships were identified between physical assault and sex, age, profession, and experience (p values 0.042, 0.000, 0.000, 0.011). CONCLUSION: Violence directed towards the emergency staff is common. Aggression occurs towards the emergency physician distinctively. Otherwise, there is no significant relationship between aggression or threat and personal characteristics. However, male sex, > or =31 years of age, being an emergency physician, and having worked for longer than five years in the emergency department are the risk factors for physical violence.

Workplace violence in emergency medicine: current knowledge and future directions.

[J]

Utilizing compassion and collaboration to reduce violence in healthcare settings. Isr

[J]

Violence in the emergency department: an ethnographic study (part II)

DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2011.07.006

URL

[Cited within: 2]

Violence in the emergency department (ED) is a significant problem and it is increasing. Nevertheless the problem remains inadequately investigated as most studies that have investigated this issue are descriptive in nature. Although these studies have provided important preliminary information, they fail to reveal the complexities of the problem, in particular the cultural aspects of violence which are crucial for the ED. This paper is part I of a 2-part series which will provide an overview of the background, aims and methods of an ethnographic study about violence in the ED. The study aimed to explore the cultural aspects of violence in the ED. Contemporary ethnography was adopted to frame the study's methodology. The study was carried out at a major metropolitan ED over 3 months using observations, questionnaires and interviews. Initially, the questionnaires were analysed using SPSS before incorporating into the qualitative data. Then, a data analysis framework was adopted to assist in the analysis of data at item (domain), pattern (taxonomic and componential) and structural levels. A brief description of the cultural scene will also be highlighted before leaving the findings of the study along with its discussions to the part II of the 2-part series. (c) 2011 Elsevier Ltd.

Violent behavior by emergency department patients with an involuntary hold status. Am

[J]

Verbal and physical violence towards hospital- and community-based physicians in the Negev: an observational study

DOI:10.1186/1472-6963-5-54

URL

PMID:16102174

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Over recent years there has been an increasing prevalence of verbal and physical violence in Israel, including in the work place. Physicians are exposed to violence in hospitals and in the community. The objective was to characterize acts of verbal and physical violence towards hospital- and community-based physicians. METHODS: A convenience sample of physicians working in the hospital and community completed an anonymous questionnaire about their experience with violence. Data collection took place between November 2001 and July 2002. One hundred seventy seven physicians participated in the study, 95 from the hospital and 82 from community clinics. The community sample included general physicians, pediatricians, specialists and residents. RESULTS: Ninety-nine physicians (56%) reported at least one act of verbal violence and 16 physicians (9%) reported exposure to at least one act of physical violence during the previous year. Fifty-one hospital physicians (53.7%) were exposed to verbal violence and 9 (9.5%) to physical violence. Forty-eight community physicians (58.5%) were exposed to verbal violence and 7 (8.5%) to physical violence. Seventeen community physicians (36.2%) compared to eleven hospital physicians (17.2%) said that the violence had a negative impact on their family and on their quality of life (p < 0.05). The most common causes of violence were long waiting time (46.2%), dissatisfaction with treatment (15.4%), and disagreement with the physician (10.3%). CONCLUSION: Verbal and/or physical violence against physicians is common in both the hospital and in community clinics. The impatience that accompanies waiting times may have a cultural element. Shortening waiting times and providing more information to patients and families could reduce the rate of violence, but a cultural change may also be required.

Michigan College of Emergency Physicians Workplace Violence Task Force. Workplace violence: a survey of emergency physicians in the state of Michigan

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.10.010

URL

[Cited within: 2]

Study objective

We seek to determine the amount and type of work-related violence experienced by Michigan attending emergency physicians.

Methods

A mail survey of self-reported work-related violence exposure during the preceding 12 months was sent to randomly selected emergency physician members of the Michigan College of Emergency Physicians. Work-related violence was defined as verbal, physical, confrontation outside of the emergency department (ED), or stalking.

Results

Of 250 surveys sent, 177 (70.8%) were returned. Six were blank (3 were from retired emergency physicians), leaving 171 (68.4%) for analysis. Verbal threats were the most common form of work-related violence, with 74.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] 68.4% to 81.4%) of emergency physicians indicating at least 1 verbal threat in the previous 12 months. Of the emergency physicians responding, 28.1% (95% CI 21.3% to 34.8%) indicated that they were victims of a physical assault, 11.7% (95% CI 6.9% to 16.5%) indicated that they were confronted outside of the ED, and 3.5% (95% CI 0.8% to 6.3%) experienced a stalking event. Emergency physicians who were verbally threatened tended to be less experienced (11.1 versus 15.1 years in practice; mean difference −4.0 years [95% CI −6.4 to −1.6 years]), as were those who were physically assaulted (9.5 versus 13.1 years; mean difference −3.6 years [95% CI −5.9 to −1.3 years]). Urban hospital location, emergency medicine board certification, or on-site emergency medicine residency program were not significantly associated with any type of work-related violence. Female emergency physicians were more likely to have experienced physical violence (95% CI 1.4 to 5.8) but not other types of violence. Most (81.9%; 95% CI 76.1% to 87.6%) emergency physicians were occasionally fearful of workplace violence, whereas 9.4% (95% CI 5.0% to 13.7%) were frequently fearful. Forty-two percent of emergency physicians sought various forms of protection as a result of the direct or perceived violence, including obtaining a gun (18%), knife (20%), concealed weapon license (13%), mace (7%), club (4%), or a security escort (31%).

Conclusion

Work-related violence exposure is not uncommon in EDs. Many emergency physicians are concerned about the violence and are taking measures, including personal protection, in response to the fear.

The relationship between workplace violence, perceptions of safety, and professional quality of life among emergency department staff members in a Level 1 Trauma Centre

DOI:10.1016/j.ienj.2018.01.006

URL

PMID:29402717

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Emergency department staff members are frequently exposed to workplace violence which may have physical, psychological, and workforce related consequences. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between exposure to workplace violence, tolerance to violence, expectations of violence, perceptions of workplace safety, and Professional Quality of Life (compassion satisfaction - CS, burnout - BO, secondary traumatic stress - STS) among emergency department staff members. METHODS: A cross-sectional design was used to survey all emergency department staff members from a suburban Level 1 Trauma Centre in the western United States. RESULTS: All three dimensions of Professional Quality of Life were associated with exposure to non-physical patient violence including: general threats (CS p=.012, BO p=.001, STS p=.035), name calling (CS p=.041, BO p=.021, STS p=.018), and threats of lawsuit (CS p=.001, BO p=.001, STS p=.02). Tolerance to violence was associated with BO (p=.004) and CS (p=.001); perception of safety was associated with BO (p=.018). CONCLUSION: Exposure to non-physical workplace violence can significantly impact staff members' compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Greater attention should be paid to the effect of non-physical workplace violence. Additionally, addressing tolerance to violence and perceptions of safety in the workplace may impact Professional Quality of Life.

Rates of workplace aggression in the emergency department and nurses’ perceptions of this challenging behaviour: a multimethod study

DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2016.05.002

URL

PMID:27259588

[Cited within: 2]

INTRODUCTION: Over the last 10 years, the rate of people presenting with challenging behaviour to emergency departments (EDs) has increased and is recognised as a frequent occurrence facing clinicians today. Challenging behaviour often includes verbal aggression, physical aggression, intimidation and destruction of property. AIM: The aim of this research was to (i) identify the characteristics and patterns of ED-reported incidents of challenging behaviour and (ii) explore emergency nurses' perceptions of caring for patients displaying challenging behaviour. METHODS: This was a multi-method study conducted across two metropolitan Sydney district hospitals. Phase 1 involved a 12-month review of the hospital's incident management database. Phase 2 involved a survey of emergency nurses' perceptions of caring for patients displaying challenging behaviour. RESULTS: Over 12 months there were 34 incidents of aggression documented and the perpetrators were often male (n=18; 53.0%). The average age was 34.5 years. The majority of reported incidents (n=33; 90.1%) involved intimidation, verbal assault and threatening behaviour. The median time between patient arrival and incident was 109.5min (IQR 192min). The median length of stay for patients was 302.5min (IQR 479min). There was no statistical difference between day of arrival and time of actual incident (t-test p=0.235), length of stay (t-test p=0.963) or ED arrival to incident time (t-test p=0.337). The survey (n=53; 66.2%) identified the average ED experience was 12.2 years (SD 9.8 years). All participants surveyed had experienced verbal abuse and/or physical abuse. Participants (n=52) ranked being spat at (n=37; 71.1%) the most difficult to manage. Qualitative survey open-ended comments were analysed and organised thematically. THEMATIC ANALYSIS: The survey identified three themes which were (i) increasing security, (ii) open access and (iii) rostering imbalance. CONCLUSION: The study provides insight into emergency nurses' reported perceptions of patients who display challenging behaviour. All emergency nurse participants reported being regularly exposed to challenging behaviour and this involved both physical and verbal abuse. This was in contrast to a low incident hospital reporting rate. ED clinicians need to be better supported with targeted educational programmes, appropriate ED architecture and reporting mechanism that are not onerous.

The epidemiology of emergency department trauma discharges in the United States

DOI:10.1111/acem.13223

URL

PMID:28493608

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: Injury-related morbidity and mortality is an important emergency medicine and public health challenge in the United States. Here we describe the epidemiology of traumatic injury presenting to U.S. emergency departments (EDs), define changes in types and causes of injury among the elderly and the young, characterize the role of trauma centers and teaching hospitals in providing emergency trauma care, and estimate the overall economic burden of treating such injuries. METHODS: We conducted a secondary retrospective, repeated cross-sectional study of the Nationwide Emergency Department Data Sample (NEDS), the largest all-payer ED survey database in the United States. Main outcomes and measures were survey-adjusted counts, proportions, means, and rates with associated standard errors (SEs) and 95% confidence intervals. We plotted annual age-stratified ED discharge rates for traumatic injury and present tables of proportions of common injuries and external causes. We modeled the association of Level I or II trauma center care with injury fatality using a multivariable survey-adjusted logistic regression analysis that controlled for age, sex, injury severity, comorbid diagnoses, and teaching hospital status. RESULTS: There were 181,194,431 (SE = 4,234) traumatic injury discharges from U.S. EDs between 2006 and 2012. There was a mean year-to-year decrease of 143 (95% CI = -184.3 to -68.5) visits per 100,000 U.S. population during the study period. The all-age, all-cause case-fatality rate for traumatic injuries across U.S. EDs during the study period was 0.17% (SE = 0.001%). The case-fatality rate for the most severely injured averaged 4.8% (SE = 0.001%), and severely injured patients were nearly four times as likely to be seen in Level I or II trauma centers (relative risk = 3.9 [95% CI = 3.7 to 4.1]). The unadjusted risk ratio, based on group counts, for the association of Level I or II trauma centers with mortality was risk ratio = 4.9 (95% CI = 4.5 to 5.3); however, after sex, age, injury severity, and comorbidities were accounted for, Level I or II trauma centers were not associated with an increased risk of fatality (odds ratio = 0.96 [95% CI = 0.79 to 1.18]). There were notable changes at the extremes of age in types and causes of ED discharges for traumatic injury between 2009 and 2012. Age-stratified rates of diagnoses of traumatic brain injury increased 29.5% (SE = 2.6%) for adults older than 85 and increased 44.9% (SE = 1.3%) for children younger than 18. Firearm-related injuries increased 31.7% (SE = 0.2%) in children 5 years and younger. The total inflation-adjusted cost of ED injury care in the United States between 2006 and 2012 was $99.75 billion (SE = $0.03 billion). CONCLUSIONS: Emergency departments are a sensitive barometer of the continuing impact of traumatic injury as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Level I or II trauma centers remain a bulwark against the tide of severe trauma in the United States, but the types and causes of traumatic injury in the United States are changing in consequential ways, particularly at the extremes of age, with traumatic brain injuries and firearm-related trauma presenting increased challenges.

Violence and aggression in the emergency department

DOI:10.1136/emj.2005.028621

URL

PMID:16714500

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the characteristics of incidents of aggression and violence directed towards staff in an urban UK emergency department. METHODS: A retrospective review of incident report forms submitted over a 1 year period that collected data pertaining to the characteristics of assailants, the outcome of incidents, and the presence of possible contributory factors. RESULTS: A total of 218 incident reports were reviewed. It was found that the majority of assailants were patients, most were male, and the median age was 32 years. Assailants were more likely to live in deprived areas than other patients and repeat offenders committed 45 of the incidents reported during the study period. The incident report indicated that staff thought the assailant was under the influence of alcohol on 114 occasions. Incidents in which the assailant was documented to have expressed suicidal ideation or had been referred to the psychiatric services were significantly more likely to describe physical violence, as were those incidents in which the assailant was female. CONCLUSION: Departments should seek to monitor individuals responsible for episodes of violence and aggression in order to detect repeat offenders. A prospective study comprising post-incident reviews may provide a valuable insight into the causes of violence and aggression.

Workplace violence against physicians and nurses in Palestinian public hospitals: a cross-sectional study

DOI:10.1186/1472-6963-12-469

URL

PMID:23256893

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Violence against healthcare workers in Palestinian hospitals is common. However, this issue is under researched and little evidence exists. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence, magnitude, consequences and possible risk factors for workplace violence against nurses and physicians working in public Palestinian hospitals. METHODS: A cross-sectional approach was employed. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data on different aspects of workplace violence against physicians and nurses in five public hospitals between June and July 2011. The questionnaires were distributed to a stratified proportional random sample of 271 physicians and nurses, of which 240 (88.7%) were adequately completed. Pearson's chi-square analysis was used to test the differences in exposure to physical and non-physical violence according to respondents' characteristics. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used to assess potential associations between exposure to violence (yes/no) and the respondents' characteristics using logistic regression model. RESULTS: The majority of respondents (80.4%) reported exposure to violence in the previous 12 months; 20.8% physical and 59.6% non-physical. No statistical difference in exposure to violence between physicians and nurses was observed. Males' significantly experienced higher exposure to physical violence in comparison with females. Logistic regression analysis indicated that less experienced (OR: 8.03; 95% CI 3.91-16.47), and a lower level of education (OR: 3; 95% CI 1.29-6.67) among respondents meant they were more likely to be victims of workplace violence than their counterparts. The assailants were mostly the patients' relatives or visitors, followed by the patients themselves, and co-workers. Consequences of both physical and non-physical violence were considerable. Only half of victims received any type of treatment. Non-reporting of violence was a concern, main reasons were lack of incident reporting policy/procedure and management support, previous experience of no action taken, and fear of the consequences. CONCLUSIONS: Healthcare workers are at comparably high risk of violent incidents in Palestinian public hospitals. Decision makers need to be aware of the causes and potential consequences of such events. There is a need for intervention to protect health workers and provide safer hospital workplaces environment. The results can inform developing proper policy and safety measures.