Endometriosis is a common, estrogen-dependent, inflammatory, gynecologic disease process in which normal endometrial tissue is abnormally present outside the uterine cavity. [1] Endometriosis is a common cause of chronic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and infertility. Most commonly, endometriosis is found within the pelvis, specifically on the ovaries. Because of rupture, bleeding, infection, or torsion, ovarian endometriosis (OMA) may cause acute abdominal pain, which is similar to acute abdominal pain caused by other reasons and is not easy to diagnose.[2,3] Determining the clinical and pathological features of OMA is crucial for accurate assessment, diagnosis, and treatment.

Surgical intervention within 72 h after rupture is recommended to reduce the impact of cyst fluid and prevent complications such as adhesions and infections.[4] However, if there is widespread adhesion or concurrent intestinal endometriosis, the risk of serious complications during surgery is higher, making elective surgery the first choice. One study suggested that elective surgery is feasible and safe for some patients suspected of having ruptured OMA,[5] but there is still uncertainty regarding the outcomes of surgical treatment for OMA manifesting as acute abdominal pain. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinico-pathological characteristics and outcomes of patients with OMA manifesting as acute abdominal pain who underwent surgical intervention.

A retrospective study was conducted at the Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, from January 2022 to March 2024, with approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the hospital (IRB-20240180-R). The eligible participants were patients between the ages of 18 and 51 years who were hospitalized for acute abdominal pain and subsequently diagnosed with OMA.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) acute onset of abdominal pain within five days prior to admission; (2) OMA confirmed by surgical intervention; (3) OMA confirmed by histology; and (4) limited to stage III/IV endometriosis according to the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (r-ASRM) classification. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) uterine bleeding; (2) recent pregnancy, previous pelvic surgery, assisted reproductive technology or non-reproductive tract infection within three months; (3) genital malformation; or (4) history of malignant tumors in the reproductive tract.

The patients’ general information, history of dysmenorrhea and endometriosis, clinical manifestations (including clinical symptoms and signs), laboratory test results, and imaging results were obtained from electronic medical records. Two endometriosis experts reviewed the surgical results and outcomes.

The included patients were classified into the progressive group (patients with complications such as rupture, infection, or torsion) and the stable group (patients without these complications) on the basis of surgical and pathological findings. The primary outcome was the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients. The secondary outcome was operative outcomes, including severe complications according to the Clavien-Dindo grading system (≥ grade III complications requiring additional surgery).

The data were analyzed via SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS, Inc., USA). Student’s t test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used for normally distributed variables and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. The Chi-square test was applied for categorical variables. A P-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

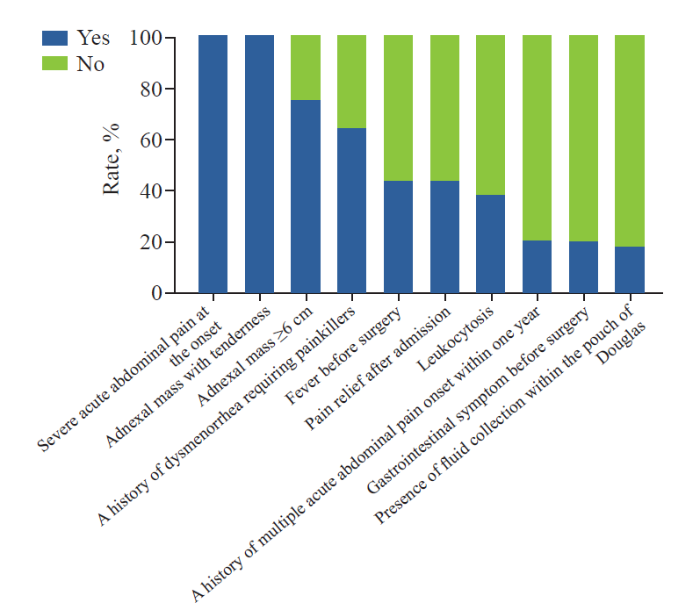

The study included 124 patients, with an average age of 33.5 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 21.7 kg/m2. The main features included severe acute abdominal pain at onset, pain relief after sudden onset of acute abdominal pain, enlargement of the adnexal mass with tenderness, and a history of dysmenorrhea (Figure 1). Fever and gastrointestinal symptoms are common atypical symptoms. Among all patients, 87 (70.1%) had no previous history of endometriosis. Leukocytosis (WBC counts >10,000/mL) was found in 51 (41.1%) patients. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels at admission were tested in 103 patients, with an average level of 47.9 mg/L. Serum CA-125 levels at admission were tested in 92 patients, with an average level of 102.5 U/mL, with levels ≥500 U/mL in 7 patients.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The main features of ovarian endometriosis manifesting as acute abdominal pain.

An initial diagnosis of acute abdominal pain caused by OMA was made in only 63 (50.8%) patients at admission. The other patients were suspected of having acute abdominal pain caused by pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), corpus luteum rupture, non-endometrioid cyst rupture, acute appendicitis or intestinal obstruction at admission and were finally diagnosed with acute abdominal pain caused by OMA through surgery.

For imaging diagnostic tools, ultrasound, as a first-line diagnostic tool, was used in all patients. OMA was confirmed by ultrasound in 66 (53.2%) patients, and additional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans were performed in 32 patients. For patients with uncertain diagnoses, surgical exploration was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Among all patients, 69 (55.6%) patients were in the progressive group, and 55 (44.4%) patients were in the stable group. Ruptured cysts were the most common manifestations in the progressive group (68.1%), followed by infected (30.4%) and twisted (1.5%) cysts. The incidence of acute abdominal pain at onset requiring a painkiller, fever, free fluid accumulation within the pouch of Douglas, and leukocytosis was higher in the progressive group than in the stable group (all P<0.05) (Table 1). The size of the adnexal mass in the progressive group was smaller than that in the stable group (P=0.01).

Table 1. Comparison of manifestations between the progressive group and the stable group

| Variables | Progressive group (n=69) | Stable group (n=55) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 33.7±7.7 | 33.4±8.2 | 0.86 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean±SD | 21.6±3.1 | 21.8±2.9 | 0.70 |

| Gravidity, mean (IQR) | 1 (0-1.5) | 1 (1-2) | 0.11 |

| Parity, mean (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 1 (0-1) | 0.13 |

| The accuracy of the first diagnosis of endometriosis at admission, n (%) | 30 (43.5) | 33 (60.0) | 0.07 |

| A history of sudden lower abdominal pain within one year, n (%) | 11 (15.9) | 15 (27.3) | 0.12 |

| A history of dysmenorrhea requiring painkillers, n (%) | 39 (56.5) | 40 (72.7) | 0.06 |

| Severe abdominal pain at the onset requiring painkillers, n (%) | 37 (53.6) | 15 (27.3) | <0.01 |

| Progressive lower abdominal pains, n (%) | 14 (20.3) | 12 (21.8) | 0.84 |

| Fever, n (%) | 41 (59.4) | 13 (23.6) | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, n (%) | 17 (24.6) | 7 (12.7) | 0.10 |

| Free fluid accumulation within the pouch of Douglas, n (%) | 21 (30.3) | 1 (1.8) | <0.01 |

| OMA diagnosed by ultrasound at admission, n (%) | 37 (53.6) | 29 (52.7) | 0.92 |

| Maximum diameter of adnexal mass under ultrasound, cm, mean±SD | 6.5±1.7 | 7.4±2.1 | 0.01 |

| Leukocytosis, n (%) | 35 (50.7) | 16 (29.1) | 0.02 |

| Complete obliteration of pouch of Douglas, n (%) | 22 (40.0) | 36 (52.2) | 0.18 |

| Surgical interventions within 24 h, n (%) | 30 (43.5) | 13 (23.6) | 0.02 |

| Surgical complications (Clavien-Dindo grading III-IV), n (%) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (5.5) | 0.80 |

Leukocytosis: white blood cell counts higher than 10,000/mL; BMI: body mass index; OMA: ovarian endometrioma.

Surgical interventions within 24 h after admission were performed in 43 (34.7%) patients. The primary indication for surgical intervention within 24 h was to facilitate diagnosis and to alleviate clinical symptoms. Compared with those in the stable group, the patients in the progressive group underwent more surgical interventions within 24 h after admission (P=0.02). Elective surgery was more common in the stable group. The grade III and IV complications included ureteral stent implantation in 4 patients and diabetes ketoacidosis in one patient. A patient who experienced cyst rupture had hemoperitoneum.

This study revealed that the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain caused by OMA is not easy. Pain relief after sudden onset of acute abdominal pain, enlargement of the adnexal mass with tenderness, and a history of dysmenorrhea requiring painkillers are important indicators of OMA manifesting as acute abdominal pain. Patients with progressive OMA are more likely to have severe abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis. For stable patients, elective surgery has been proven to be safe, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study.[5]

Elevated biomarkers such as white blood cell count and serum CRP and CA-125 levels are notable but lack specificity, suggesting the need for improved diagnostic biomarkers in emergency situations.[6] Although ultrasound is a first-line diagnostic tool,[7] it is limited in evaluating complicated OMA because of atypical cyst features. MRI could provide more detailed imaging findings for suspected endometriosis.[8] Patients who underwent OMA surgery had more perioperative adverse events than did those with other benign ovarian cysts.[9] Complete occlusion of the pouch of Douglas and concurrent deep infiltrating endometriosis may increase the risk of surgical complications.[10] Balancing the risks and benefits of surgical intervention is crucial in the emergency management of endometriosis. Our study supports early intervention and emphasizes the efficacy of elective surgery when clinical conditions are stable.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design. Only clinical data from a single center specializing in obstetrics and gynecology were used.

Further research is needed to explore long-term outcomes of surgical intervention for OMA, particularly in terms of postoperative recovery, and prevention of recurrence and potential genetic or biomolecular markers of OMA, which can help us better understand OMA and improve treatment.

Funding: This work was supported by 4+X Clinical Research Project of Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (ZDFY2021-4X202).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the hospital (IRB-20240180-R).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: ZYC conceived drafted the manuscript. ZYC, TS, YQZ,YYZ, XYL and JBL collected the clinical data. ZYC and YQZ revised the manuscript. All authors revised the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Reference

Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations

Acute abdominal pain in non-pregnant endometriotic patients: not just dysmenorrhoea. A systematic review

Spontaneous uterine perforation of pyometra leads to acute abdominal pain and septic shock: a case report

Suitable timing of surgical intervention for ruptured ovarian endometrioma

Clinical features of patients with previous spontaneous rupture of ovarian endometrioma operated electively: a case-control study

High CA-125 and CA19-9 levels in spontaneous ruptured ovarian endometriomas

Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for detection of endometriosis using International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) approach: prospective international pilot study

Gynaecological causes of acute pelvic pain: common and not-so-common imaging findings

Perioperative outcomes in a nationwide sample of patients undergoing surgical treatment of ovarian endometriomas

Clinical outcomes following surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis