With the rapid development of emergency medicine, emergency physicians are working around the clock,[1] including additional workloads due to sudden public health emergencies and disasters. Occupational risks for emergency physicians are significantly high due to an increasing number of patients with acute and severe diseases, an increased workload, and a potential danger of medical malpractice.[2] The emergency department (ED) environment is frequently characterized by stresses and uncertainty, with a high incidence of trauma and violence.[3,4] An increasing occupational risk leads to a vicious circle of physicians losing patience and subsequently compromising doctor-patient relationships. This study aimed to explore the occupational risks of emergency physicians and their causes in China, in order to pursuing and delivering a high quality of emergency care.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (2022-01-021-05). We conducted a cross-sectional investigation among physicians on duty in 24-hour EDs. Other non-clinical staff, such as administrators, secretaries, full-time scientific researchers, and full-time teaching staff in the EDs, were excluded. The participants were mainly from EDs of first-tier cities in China characterized by limited medical resources, large population flows, and high demands for emergency services. A questionnaire was designed based on the relevant literature, practical and personal experiences, and expert consultations. The study was conducted from November 16 to December 10, 2021.

Data were collected via an online questionnaire accessible on mobile phones. Informed consents were obtained from all participants prior to participation. The questionnaire collected demographic and professional information, including sex, age, years of working experience, working hours, job title, exposure risk, mental stress, occupational satisfaction, and countermeasures for these risks.

To ensure the quality of the data, the questionnaires were distributed by the Emergency Medicine Society of the Chinese Medical Association, and the returned answers were cross-checked by the investigators. Any missing or anomalous data were sent back to the responsible physicians for further verification.

The open-ended question results were summarized using Microsoft Office Excel™. SPSS 20.0 (IBM, USA) was utilized for statistical analysis. Skewed continuous variables are reported as medians with interquartile ranges, and normally distributed variables are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Between-group comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentages and were compared using the Pearson Chi-square test. All tests were two-tailed and performed at the 5% significance level.

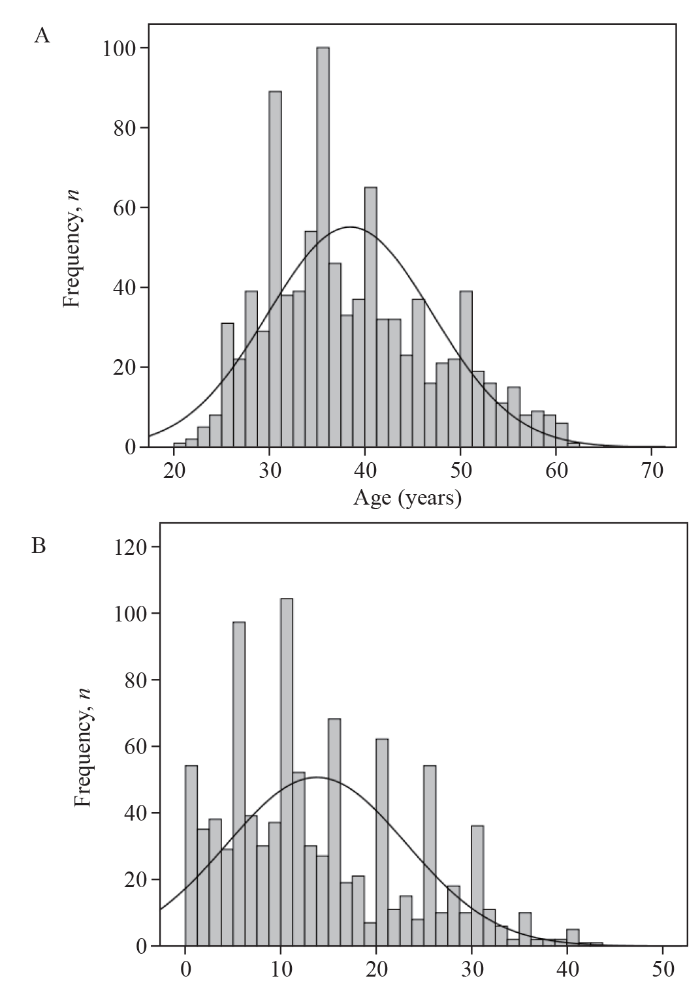

A total of 953 qualified questionnaires were analyzed from 1,120 emergency physicians, yielding an 85.1% valid response rate. The sample consisted of 599 male and 354 female physicians across 24 territories in China, with an average age of 38.4±8.6 years (Figure 1A). As the backbone of EDs, attending physicians and resident physicians accounted for 64% of the participants.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age and working experience.

The average working experience of emergency physicians in hospitals was 12 years, with an interquartile range of 6 to 20 years (Figure 1B). More details can be found in supplementary Table 1.

The average working time for emergency physicians was 9.7±2.2 h per day and 58.2±13.2 h per week. Among them, 69.5% had a normal workload of 8-10 h per day.

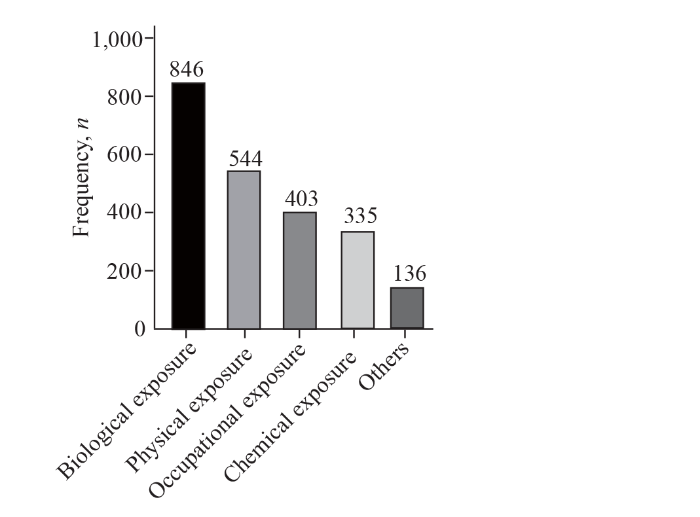

The most common exposure risk for emergency physicians was biological, including contact with infected blood, excretions, or other body fluids, reported by 88.8%. The second most common exposure risk was physical, involving exposure to medical sharp instruments, for a total of 57.1%. This was followed by occupational exposure and chemical exposure, which involved trauma caused by tumbles, sprains, or bumps and contact with sanitizers, chemotherapeutic agents (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The frequency of exposure risks.

The emergency physicians reported experiencing mental stress due to the increasing number of patients with acute and severe diseases, the increased workload, and the potential danger of medical malpractices.

When asked about occupational satisfaction, some emergency physicians expressed dissatisfaction with their career development. The primary cause was a lack of understanding and emotional support (41.9%), difficulties in achieving a work-life balance (39.4%), challenges in obtaining a sense of accomplishment from their work, obstacles to promotion, and poor interpersonal relationships and workplace atmosphere (supplementary Table 2).

Physicians, who aged between 30 and 40 years or who had 10 to 20 years of professional experience reported lower occupational satisfaction. Attending physicians or associate chief physicians expressed lower occupational development satisfaction (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in mental stress among participants at various professional levels. The main findings are presented in supplementary Table 3.

During the diagnosis and treatment processes, emergency physicians must handle with blood, body fluids, urine, feces, vomitus, and secretions of patients in some invasive operations, which are associated with a high risk of biological exposure. In addition, disinfectants are often used in EDs, which cause long-term exposures to human skin, mucous membranes, respiratory tract, and nervous system,[7] and cause chest tightness and headaches, even asthma, pulmonary edema, occupational dermatitis, and ophthalmia. All these factors result in a heightened risk of occupational exposure and may have adverse effects on health.[8]

Owing to the nature of their work, emergency physicians face an imbalance between work and family, feel guilty about being unable to fulfill their family duties that further aggravates their pressures at work.[9]

Overload and high pressure at work, and physical and psychological discomfort decrease emergency physicians’ occupational satisfaction. A report showed that the career satisfaction of emergency physicians was 65.2%.[10] However, our data showed that occupational satisfaction decreases with age and professional title. The reason may be that young physicians have higher enthusiasm for work and fewer burdens on their livelihood. As time progresses, the pressure of work and life leads to job burnout and consequently results less occupational satisfaction. As income and social status stabilize and work experiences increase, physicians become more experienced in communicating with patients that improves their career satisfaction.

Based on the above analysis, we proposed some countermeasures to improve and minimize occupational risks for emergency physicians. For physicians, they must pay more attention to recognizing occupational risks and preventing potential harm. Socially, it is necessary to publicize medical and legal knowledge to patients, and litigation channels must be improved to prevent violent injuries to physicians.[11]

There are some limitions of the study. First, our data were self-reported and not verified by others. Second, the loss in data from our survey may more likely represent dissatisfied physicians, which may influence the results. Third, the terms “burnout” and “stress” were not defined in the survey, so all the physicians may not have had the same understanding of these words when completing the survey.

Our study provides an overview of emergency physicians’ occupational risks in China. Measures to decrease occupational risks are needed to improve working conditions for emergency physicians.

Funding: Beijing Key Specialized Department for Major Epidemic Prevention and Control (Construction Project); National Major Science and Technology Projects (2017ZX10305501), Beijing Social Science Foundation Planning Project (17SRC019)

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine (2022-01-021-05).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: HYJ and JC contributed equal to this article. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.

Reference

Investigation on mental health status of medical staff in emergency department of general hospital

Influence of work stress on physical and mental health of medical staff in emergency department

Salivary cortisol levels and work-related stress among emergency department nurses

PMID:11765672

[Cited within: 1]

The objective of this study was to assess and compare the self-perceived work-related stress of emergency department (ED) and general ward (GW) nurses and to assess the relationship between self-perceived stress and salivary cortisol levels in these groups of nurses. Seventy-three female ED (n = 23) and GW (n = 50) nurses from a general hospital completed a self-administered questionnaire. A modified mental health professional stress scale (PSS) was used to measure self-perceived work-related stress. Salivary samples were collected at the start and end of morning shiftwork. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method was used to determine the salivary cortisol concentration (nmol/L). ED nurses perceived that nursing was more stressful (mean, 1.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35 to 1.81) than did GW nurses (mean, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.40). On the PSS subscales, scores of organizational structure and process, lack of resources, and conflict with other professionals were higher in ED nurses (all P < 0.01). The morning cortisol was significantly lower in ED (geometric mean, 9.10; 95% CI, 6.62 to 12.42 nmol/L) than in GW (geometric mean, 15.45; 95% CI, 11.86 to 20.14 nmol/L) nurses. Log morning salivary cortisol was negatively correlated with PSS (r = -0.255), scores of organizational structure and process, and conflict with other professionals (all P < 0.05). The difference between morning and afternoon cortisol concentration in ED nurses (geometric mean, 6.35; 95% CI 4.14 to 9.93 nmol/L) was lower than in GW nurses (geometric mean, 12.42; 95% CI, 9.38 to 16.28 nmol/L). The log value of the difference correlated marginally with PSS (r = -0.21, P = 0.07) and significantly with scores of organizational structure and process, lack of resources, and conflict with other professionals (all P < 0.05). There was no difference between the two groups in afternoon salivary cortisol level. ED nurses perceived more stress compared with GW nurses. Morning salivary cortisol concentration is better correlated with PSS compared with the morning-afternoon salivary cortisol difference. The result raises the possibility of using a single morning salivary cortisol sample to reflect self-perceived stress.

Workplace bullying: concerns for nurse leaders

DOI:10.1097/NNA.0b013e318195a5fc

PMID:19190425

[Cited within: 1]

The aim of this study was to describe nurses' experiences with and characteristics related to workplace bullying.Although the concept of workplace bullying is gaining attention, few studies have examined workplace bullying among nurses.This was a descriptive study using a convenience sample of 249 members of the Washington State Emergency Nurses Association. The Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised was used to measure workplace bullying.Of the sample, 27.3% had experienced workplace bullying in the last 6 months. Most respondents who had been bullied stated that they were bullied by their managers/directors or charge nurses. Workplace bullying was significantly associated with intent to leave one's current job and nursing.In seeking remedies to the problem of workplace bullying, nurse leaders need to focus on why this bullying occurs and on ways to reduce its occurrence. This is a critical issue, since it is linked with nurse attrition.

The current situation and countermeasures of doctor-patient relationship in emergency department

Factors influencing the turnover intention of Chinese community health service workers based on the investigation results of five provinces

Discussion on occupational risk and prevention of medical staff in emergency department

Occupational risk factors and protective countermeasures of nurses in emergency department

The relationship between job satisfaction, work stress, work-family conflict, and turnover intention among physicians in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study

Career satisfaction in emergency medicine: the ABEM longitudinal study of emergency physicians

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.005

PMID:18395936

[Cited within: 1]

The primary objective of this study is to measure career satisfaction among emergency physicians participating in the 1994, 1999, and 2004 American Board of Emergency Medicine Longitudinal Study of Emergency Physicians. The secondary objectives are to determine factors associated with high and low career satisfaction and burnout.This was a secondary analysis of a cohort database created with stratified, random sampling of 1,008 emergency physicians collected in 1994, 1999, and 2004. The survey consisted of 25 questions on professional interests, attitudes, and goals; 17 questions on training, certification, and licensing; 36 questions on professional experience; 4 questions on well-being and leisure activities; and 8 questions about demographics. Data were analyzed with a descriptive statistics and panel series regression modeling (Stata/SE 9.2 for Windows). Questions relating to satisfaction were scored with a 5-point Likert-like scale, with 1=not satisfied and 5=very satisfied. Questions relating to stress and burnout were scored with a 5-point Likert-like scale, with 1=not a problem and 5=serious problem. During analysis, answers to the questions "Overall, how satisfied are you with your career in emergency medicine?" "How much of a problem is stress in your day-to-day work for pay?" "How much of a problem is burnout in your day-to-day work for pay?" were further dichotomized to high levels (4, 5) and low levels (1, 2).Response rates from the original cohort were 94% (945) in 1994, 82% (823) in 1999, and 76% (771) in 2004. In 2004, 65.2% of emergency physicians reported high career satisfaction (4, 5), whereas 12.7% of emergency physicians reported low career satisfaction (1, 2). The majority of respondents (77.4% in 1994, 80.6% in 1999, 77.4% in 2004) stated that emergency medicine has met or exceeded their career expectations. Despite overall high levels of career satisfaction, one-third of respondents (33.4% in 1994, 31.3% in 1999, 31% in 2004) reported that burnout was a significant problem.Overall, more than half of emergency physicians reported high levels of career satisfaction. Although career satisfaction has remained high among emergency physicians, concern about burnout is substantial.

Prevention of violent injury to doctors based on risk assessment