Dear editor,

Iatrogenic hypoglycaemia is a common acute presentation; either because of misuse, self-harm or criminal intent. The most common culprits are insulin and oral hypoglycaemics (sulfonylurea, biguanides) although aspirin, fluoroquinolone and beta blockers can be causative agents. Common symptoms include sweating, anxiety, tremors, and palpitations. Neuroglycopenic symptoms usually arise at serum glucose concentrations of <2.8 mmol/L and include dizziness, confusion, blurred vision, somnolence and more serious symptoms can be convulsions, coma and potentially death.

Sulfonylureas reduce the glucose levels by displacing insulin from the Beta cells in the pancreas. They are well absorbed in the gut and have an oral bioavailability of up to 80% and are extensively bound to albumin which contributes to their longer duration of action of 12-24 h. Standard management of hypoglycaemia with dextrose is only effective transiently as a stop gap. Owing to their longer duration of action and potentially active metabolites, hypoglycaemia can persist. Octreotide use is first line therapy, however, dosing has not been fully established. Our case discusses a patient who had refractory hypoglycaemia which persisted despite dextrose boluses and dextrose infusion.

CASE

A 30-year-old gentleman with a medical history of previous intravenous (IV) drug use was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) after he was found collapsed and drowsy while in police custody. He was found to have a reduced Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), low body temperature and low blood glucose in the pre-hospital setting. Paramedics noted that he had a blood glucose level of 2.3 mmol/L and administered intramuscular glucagon plus three doses of intramuscular naloxone. There was a transient improvement in his blood sugar to 4.1. He was suspected of having taken a mixed drugs overdose but at the time of presentation there was no detail available with regards to which drugs were taken. Blood glucose reading in hospital was found to be 3.1 mmol/L.

Further glucagon and glycogen were administered. He was tolerating an oropharyngeal airway, and had increased work of breathing, mild tachycardia and cool peripheries. Because of a persistently low GCS (7 points), he required intubation and ventilation in the ED. Due to difficult IV access he had an intraosseous (IO) sited prior to rapid sequence induction and a central venous catheterisation (CVC) sited by the critical care team immediately afterwards. An arterial line was also sited in ED while awaiting computed tomography (CT) imaging. He remained cardiovascularly stable after intubation with a lactate of 2 mmol/L, however, his blood glucose were critically low (less than 3 mmol/L) when reviewed in ED via arterial blood gas. He required treatment on three different occasions with 50 mL of 50% IV dextrose. CT head imaging was normal and after this he was transferred to Critical Care Unit. He was started on background IV fluids with 20% dextrose infusion running at 25 mL/h, but continued to have low blood glucose despite the fluids.

Differential diagnoses for reduced GCS and hypoglycaemia

(1) Significant alcohol ingestion: no evidence of acid/base disturbance. (2) Ethylene glycol poisoning: no evidence of acidosis/normal anion gap. (3) Neurotrauma: excluded by nil acute findings on CT brain imaging. (4) Beta-blocker overdose: given unaltered haemodynamic status, this was unlikely. (5) Excess insulin administration or neuro-endocrine tumour (insulinoma): unlikely to having been a co-incidence, however C-peptide levels were requested. (6) Other endocrinology emergencies (e.g., Addisonian crisis): unlikely given normal biochemistry profile.

Management

Having been admitted to the Critical Care Unit, there were still concerns of requiring large volumes of IV dextrose to maintain a reasonable blood glucose level. He had regular arterial blood gas analysis results which revealed no derangement in the acid/base status with normal lactate levels. A toxicology screen was carried out which revealed no abnormality.

Whilst our patient continued to receive infusions of dextrose, the underlying cause of hypoglycaemia was investigated. There was no immediate toxidrome that would explain the unremarkable arterial blood gas analysis with the aforementioned persistent hypoglycaemia. The two main causes were then investigated for both exogenous administration of insulin or the rare co-existent neuroendocrine tumour. A C-peptide level was requested, however, the result would have not been immediately available as this was processed in a distant lab.

Having had a discussion with the police officers and with further investigation, it became apparent that he had a used box of gliclazide tablets at the time of arrest. It was unsure of how many he had ingested at the time although it was postulated that it might have been 640 mg (80 × 8 mg).

Immediate discussion with the consultant staff at the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) was carried out. It was noted that there were no specific guidelines for the management of gliclazide poisoning with the knowledge base from anecdotal evidence or from case reports.[1] There is an established practice of octreotide in management of refractory hypoglycaemia in the context of sulphonylureas poisoning.[2] There were two options to note: 100 μg subcutaneously administration or a continuous infusion. Following a discussion with NPIS, there were no differences in the clinical effectiveness using either administration. There are no current systematic reviews currently available that show treatment superiority.

The management strategy that we had undertaken was as follows: (1) Ongoing 20% dextrose infusion with top up boluses of 50 mL of 50% dextrose. (2) Two doses of octreotide 100 μg were given subcutaneously. (3) Octreotide 100 μg QDS until blood sugar stabilised. (4) Blood ketones were monitored.

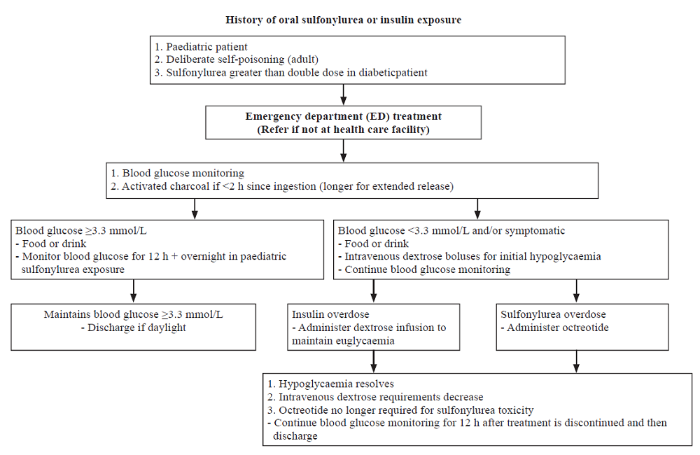

With the above management strategy our patient’s blood sugar stabilised and he was subsequently extubated. A treatment algorithm for sulfonylurea and insulin toxicity is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A treatment algorithm for sulfonylurea and insulin toxicity.

DISCUSSION

Sulfonylurea overdose can cause a profound and prolonged hypoglycaemia, usually apparent within 8 h post ingestion of a standard preparation and longer if extended preparation (up to 18 h).[3] Delayed presentation of 48 h may also occur. Ingestion of one tablet in a non-diabetic patient may cause profound hypoglycaemia. In our patient the time of ingestion was unknown upon admission to the ED. Sulfonylureas inhibit potassium efflux in the beta cells of the pancreas. As a result, insulin is released resulting in a hyperinsulinaemic state. Sulfonylureas are metabolised in the liver and excreted via the renal system. The elimination half-life is variable but prolonged in overdose.[4]

Hypoglycaemia is usually defined as a blood glucose concentration less than 3.3 mmol/L (60 mg/dL). It is generally recommended that blood glucose be monitored hourly initially and then at longer intervals (2-6 h) in a hospital setting until patient is stable on octreotide. Routine electrocardiogram (ECG), renal function, liver function and paracetamol levels should be measured upon admission to the ED in any potential overdose cases.[3,4] The initial management constitutes of immediate resuscitation as was required with our patient presenting with a low GCS and a blood sugar <4 mmol/L. An initial bolus of 50 mL of 50% dextrose is the most common approach in adults. This should be repeated as required. Once blood sugar >4 mmol/L is reached, an infusion of 10% dextrose starting at 100 mL/h should be started. Further episodes of hypoglycaemia can be treated with 50% boluses.[3] Ultimately, the dextrose is a temporary measure until octreotide can be given.

It is rarely reported that higher doses of dextrose will be required once octreotide has commenced, however if greater than 100 mL of 10% dextrose in adults is required then a CVC should be considered.[3] Where appropriate and if ingestion occurred < 2 h of admission to hospital, gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal should be administered.[4] It may be considered beyond this for extended-release preparations, however limited information is available for an exact time period.

Although IV dextrose would seem the obvious therapy for hypoglycaemia, excessive dextrose will cause hyperglycaemia and a marked increase in endogenous insulin secretion in patients with an intact pancreas, including both non‐diabetics and type II (insulin‐resistant) diabetics. Furthermore, sulfonylureas toxicity promotes a large increase in insulin for a small increase in blood glucose. A limitation with our case occurred here whereby upon admission the ingestion of the lethal medication was unknown. The patient was initially treated for the symptom of hypoglycaemia of unknown cause. IV dextrose is most effective when 50% dextrose is used as 10% dextrose only contains a small amount of glucose.

Following an initial bolus of IV dextrose in a sulfonylurea overdose, excessive IV dextrose will stimulate endogenous insulin production (most patients will have intact pancreatic function). This contributes to subsequent hypoglycaemia, and potentially further boluses of dextrose may lead to a vicious cycle of repeated dextrose boluses and rebound hypoglycaemic episodes. For this reason, octreotide rather than IV dextrose should be the main treatment in sulfonylurea overdoses.[4]

Octreotide is a long‐acting synthetic somatostatin analogue that binds to somatostatin‐2 receptors on the pancreatic beta cells, prevents the influx of calcium required for insulin secretion and therefore blocks insulin secretion. It has been used in the treatment of hypoglycaemia resulting from sulfonylurea toxicity for over 20 years. Only minor adverse effects have been reported including: injection site pain, hyperglycaemia, nausea, abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhoea, and bradycardia.[4] There are no controlled trials, so dose and dosing interval are based on limited published data. The dose can be given intravenously (50 μg bolus followed by an infusion of 25 μg/h, 1 μg/[kg·h] in children) or subcutaneously (50-100 μg in adults and 1-2 μg/kg in children every 6-12 h). Octreotide should be initially given for 12 h.[2] Based on the published clinical and pharmacokinetic data of sulfonylureas and octreotide, a published review article in 2012, suggested the following dose regimen in adults: octreotide 50 μg subcutaneously or IV, followed by three 50 μg doses every 6 h.[5]

A double-blinded randomised control trial carried out in the USA in 2008[2] was undertaken to compare the efficacy of octreotide plus standard therapy in the treatment of sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia. The results from this study show a statistically significant increase in mean glucose level among patients who received octreotide compared with placebo. The effects are most pronounced in the first 4-8 h after the administration of a single 75 μg subcutaneous dose. Recurrent hypoglycemic episodes occurred less frequently in patients who received octreotide compared with those who received placebo. There were no adverse events recorded within the first 72 h after octreotide administration.[2]

CONCLUSIONS

As highlighted in our case, the attending clinician would need a high index of suspicion for this possible diagnosis. The initial management for hypoglycaemia still involves IV dextrose with subsequent doses of octreotide for suphonlyurea related hypoglycaemia. As discussed, there is no particular treatment protocol that shows superiority for a particular treatment strategy. The importance of collateral history is paramount as was also highlighted in this case.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to take this opportunity to thank our patient and all the staff members who looked after our patient. Our patient very kindly gave consent for his case to be used for educational purposes. We are very thankful to him for enabling us to do so.

Funding: There was no funding applied for this article.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interest: The authors had no conflicts of interest in undertaking this project.

Contributors: MK involved in manuscript preparation including gaining consent from patient. NK involved in manuscript preparation including literature review. DN involved in manuscript preparation and initial patient management. DC, corresponding author, led this project including final preparation for submission.

Reference

Bench-to-bedside review: antidotal treatment of sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia with octreotide

DOI:10.1186/cc3807 URL [Cited within: 1]

Comparison of octreotide and standard therapy versus standard therapy alone for the treatment of sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.493 URL [Cited within: 4]

Sulphonylurea toxicity

Treatment of sulfonylurea and insulin overdose

DOI:10.1111/bcp.12822

PMID:26551662

The most common toxicity associated with sulfonylureas and insulin is hypoglycaemia. The article reviews existing evidence to better guide hypoglycaemia management. Sulfonylureas and insulin have narrow therapeutic indices. Small doses can cause hypoglycaemia, which may be delayed and persistent. All children and adults with intentional overdoses need to be referred for medical assessment and treatment. Unintentional supratherapeutic ingestions can be initially managed at home but if symptomatic or if there is persistent hypoglycaemia require medical referral. Patients often require intensive care and prolonged observation periods. Blood glucose concentrations should be assessed frequently. Asymptomatic children with unintentional sulfonylurea ingestions should be observed for 12 h, except if this would lead to discharge at night when they should be kept until the morning. Prophylactic intravenous dextrose is not recommended. The goal of therapy is to restore and maintain euglycaemia for the duration of the drug's toxic effect. Enteral feeding is recommended in patients who are alert and able to tolerate oral intake. Once insulin or sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia has developed, it should be initially treated with an intravenous dextrose bolus. Following this the mainstay of therapy for insulin-induced hypoglycaemia is intravenous dextrose infusion to maintain the blood glucose concentration between 5.5 and 11 mmol l(-1). After sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia is initially corrected with intravenous dextrose, the main treatment is octreotide which is administered to prevent insulin secretion and maintain euglycaemia. The observation period varies depending on drug, product formulation and dose. A general guideline is to observe for 12 h after discontinuation of intravenous dextrose and, if applicable, octreotide. © 2015 The British Pharmacological Society.

Octreotide for the treatment of sulfonylurea poisoning

DOI:10.3109/15563650.2012.734626

PMID:23046209

Sulfonylureas are used extensively for treating type-2 diabetes mellitus. Sulfonylurea poisoning can produce sustained and profound hypoglycemia refractory to IV dextrose, particularly in children and the elderly.To review the use of octreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analog, in the treatment of sulfonylurea-induced hypoglycemia.A computerized search of U.S. National Academy of Medicine, Embase, PubMed and Toxline databases was undertaken using the keywords "octreotide", "sulfonylurea", "poisoning", "intoxication", "overdose" and "children". Textbooks of Clinical Toxicology and Pharmacology and the articles cited in their bibliographies were also searched. Twenty-four publications (19 articles and five conference abstracts) were identified; no publication was excluded. PHARMACOLOGY OF OCTREOTIDE: Octreotide, a synthetic peptide analog of somatostatin, binds to G protein-coupled somatostatin-2 receptors in pancreatic beta-cells, resulting in decreased calcium influx and inhibition of insulin secretion. Octreotide markedly inhibited insulin secretion and decreased the number of hypoglycemic events and supplemental dextrose requirements in animal studies. In humans octreotide markedly inhibited insulin release, increased serum glucose concentration, reduced dextrose requirement, prevented recurrent hypoglycemia and was superior to IV dextrose and diazoxide after administration of sulfonylureas. EFFICACY OF OCTREOTIDE IN PEDIATRIC SULFONYLUREA POISONING: Fourteen pediatric patients were reported; 13 ingested second-generation sulfonylureas, with time to hypoglycemia of 1.5-16 hours. IV dextrose (10-25%) was administered before and after octreotide therapy. Octreotide was given after failure to correct hypoglycemia with IV dextrose in doses of 0.51-2 μg/kg IV or SC; two also required an IV octreotide infusion. Seven patients (50%) had recurrent hypoglycemia and received IV dextrose and additional octreotide. EFFICACY OF OCTREOTIDE IN ADULT SULFONYLUREA POISONING: Fifty-three patients were reported in prospective controlled (n = 22) and retrospective (n = 9) studies, case series (n = 6) and case reports. Fifty-one ingested second-generation sulfonylureas with time to hypoglycemia of 1-13 hours. All received IV dextrose (10-50%) before and after octreotide treatment. Octreotide 40-100 μg SC or IV was administered followed by additional doses in most patients; three patients also required an IV infusion. Octreotide significantly increased serum glucose concentrations, decreased dextrose requirement and recurrent hypoglycemic events compared with IV dextrose. Recurrent hypoglycemia was recorded in 22-50% of the patients treated with octreotide. THERAPEUTIC RECOMMENDATIONS: Based on the published clinical and pharmacokinetic data of sulfonylureas and octreotide, we suggest the following dose regimens: in children, octreotide 1-1.5 μg/kg IV or SC, followed by 2-3 more doses 6 hours apart. In adults, octreotide 50 μg SC or IV, followed by three 50 μg doses every 6 hours. During this treatment IV dextrose infusion should be gradually tapered off.Hypertension and apnea were recorded in one pediatric patient 30 minutes after IV octreotide; the relationship to octreotide is unclear. One adult patient with chronic renal failure treated with atenolol developed severe hyperkalemia.Although relatively limited, the available data suggest that octreotide should be considered first-line therapy in both pediatric and adult sulfonylurea poisoning with clinical and laboratory evidence of hypoglycemia. Maintenance doses of octreotide may be required to prevent recurrent hypoglycemia.