Dear editor,

Traumatic pneumocephalus describes the presence of gas in the brain cavity, with an incidence of 0.5%-9.7%.[1] It was first reported by Luckett.[2] It is primarily self-limiting. However, traumatic tension pneumocephalus (TTP) due to increased intracranial gas is extremely rare. It is a neurological emergency manifested by headaches, seizures, loss of consciousness, and even death resulting from high intracranial pressure. This study aimed to report a patient with TTP who had progressive deterioration of consciousness over a short period. The patient recovered well through timely neurosurgical surgery, with no discomfort during the follow-up after discharge.

CASE

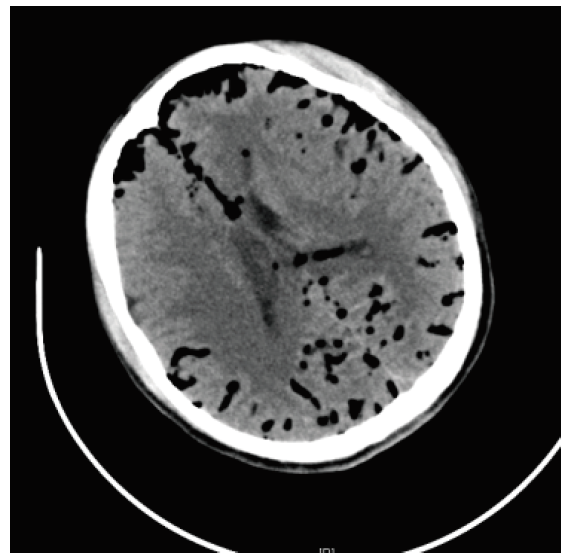

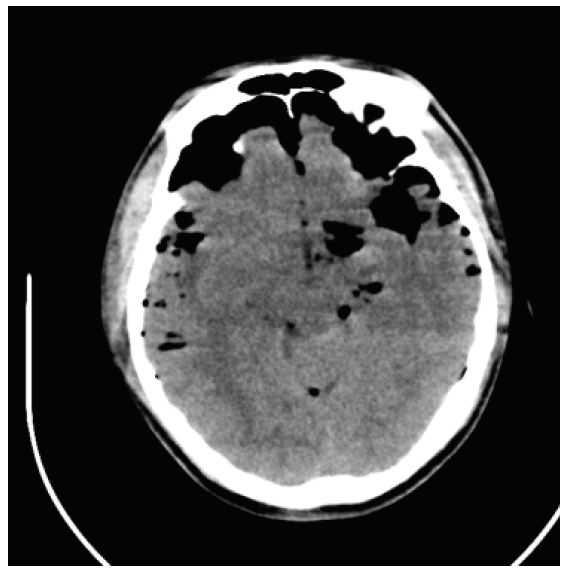

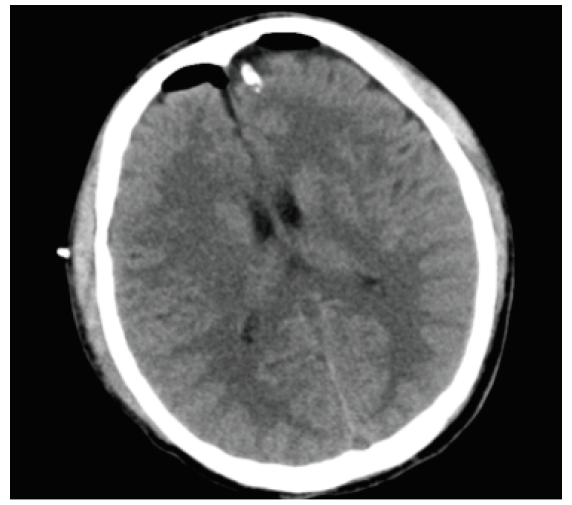

A 25-year-old man without past medical history presented to the emergency department after a motor vehicle accident. He covered his head with hands and groaned with pain. He had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14 when he arrived. He opened his eyes spontaneously (E4), had localized pain (M5), and was orientated (V5). The patient was not in a coma at the time of the accident, but a flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was observed in the nasal cavity and left external auditory canal. The bilateral pupils were equal in size and 3 mm in diameter, and had a slow luminous reflex. The patient's neck was soft and unresisted, and the examination of the heart and lungs was normal. His limb muscle strength test was not cooperative, the muscle tone was not high, and Brinell's sign, Klinefelter's sign, and Babinski's sign were all negative. The patient's emergency computed tomography (CT) scan showed pneumocephalus and no abnormalities of the chest, abdomen, or pelvis (Figure 1). Considering CSF leaks and intracranial gas buildup, the emergency physicians gave the patient oxygen therapy, replaced the appropriate fluid, and immediately transferred the patient to the intensive care unit to monitor vitals. However, within hours, the patient's GCS score decreased, consciousness deteriorated, coma appeared, and pupillary light reflex was sluggish. Endotracheal intubation was placed to protect the airway. His blood pressure, blood sugar, electrolytes, and hemoglobin were stable, with no sign of shock. We re-examined the patient's brain CT. The CT results showed that the gas was generally in the subdural space. With tension pneumocephalus, the gas pressed down on the frontal lobes, giving the brain a sharp appearance and creating the radiological sign of “Mount Fuji Sign” (Figure 2). It was an urgent matter. The neurosurgeon urgently drilled the patient's left frontal skull and placed a subdural drainage tube at a depth of approximately 4 cm; gas bubbles spilled out of the drainage tube (Figure 3). While the patient's intracranial gas was continually drained, his intracranial pressure began to fall, and his pupillary reflexes became more sensitive. We raised the patient's head by 30° to relieve intracranial pressure and brain edema following the surgery. Given that the patient had an open low cranial fracture and the wound was contaminated, he had a potential for infection. We experimentally used antibiotics within 24 h following the perioperative period. Reassuringly, the patient woke up the next day and was able to follow the instructions with no more CSF leaks. We removed the patient's ventilator and tracheal intubation, and re-examined the patient's head. The CT scan showed that the pneumocephalus was significantly reduced. Therefore, we removed the drainage tube from the patient's frontal lobe. After a week of hospital treatment, the patient was discharged. During the 3-month follow-up after discharge, the patient had no recurrence of CSF leakage and recovered well.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Brain CT scan showing pneumocephalus. CT: computed tomography.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Brain CT scan showing tension pneumocephalus. CT: computed tomography.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Brain CT scan showing a small amount of gas visible on the forehead. CT: computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

Pneumocephalus is defined as the presence of gas in the cranial vault, which is commonly associated with cranial surgery or craniofacial fractures.[3]Traumatic pneumocephalus is more common in diseases with craniocerebral injury, often accompanied by an open fracture of the base of the head,[4] CSF rhinorrhea or otorrhea damaged sinus gas or mastoid gas chamber in the skull. Gases may accumulate in the extradural, subdural, subarachnoid, intracerebral, or intraventricular spaces. The appearance of neurological symptoms or the decline associated with pneumocephalus, with high intracranial pressure, is referred to as tension pneumocephalus. However, tension pneumocephalus is rare, which is associated with increased intracranial pressure, neurological deficit, disturbance of consciousness, and even cerebral hernia and death due to more gas entering the skull.[5]

The proposed mechanisms of tension pneumocephalus are as follows.[6] (1) When the gas pressure in the sinus cavity of the skull base is suddenly raised, such as the blowing nose, coughing, or sneezing, the gas is pressed into the skull through the skull base fracture and damaged meninges. (2) When the intracranial pressure is too low, the gas is sucked into the brain through the skull base fracture and damaged meninges, especially when the patient changes his position. Its mechanism is similar to the inversion of soda bottles; therefore, some scholars call it the inversion syndrome of soda bottle.[7](3) Unidirectional function of damaged meninges causes gas to flow continuously and increases the intracranial pressure.

TTP can be diagnosed by the craniocerebral CT examination, and the location of the fracture can be confirmed. For a limited amount of non-tension intracranial pneumocephalus,[8] no special treatment is required. Antibiotics are given to prevent infection according to the principle of open craniocerebral injury; gas can often be absorbed on its own.[9] Diffuse intracranial pneumocephalus, especially when tension pneumocephalus causes an increase in the intracranial pressure, necessitates the surgical release of gases. Borehole exhaust gases are generally chosen from the front (the highest point of gas accumulation). Surgical trepanation, gas drainage, and CSF replacement have some effect on tension pneumocephalus.[10] In the case of open craniocerebral injury or penetrating brain injury with intracranial pneumocephalus, the dura mater should be repaired by debridement. Recurrent pneumocephalus with CSF leakage is treated surgically according to the principle of CSF leakage repair. The volume of the liquid should be increased after the surgery to close the emphysema chamber.

CONCLUSION

Early monitoring is important for patients with traumatic pneumocephalus, as it may lead to tension pneumocephalus that is a disease with rapid development and high mortality and requires prompt surgical intervention.

Funding: The study was supported by Chinese Medicine Rehabilitation Service Capacity Improvement Project from the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2022.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors: All authors contributed substantially to the writing and revision of this manuscript and approved its final version.

Reference

Acute management of tension pneumocephalus in a pediatric patient: a case report

Air in the ventricle of the brain following a fracture of the skull

Tension pneumocephalus

Treatment of pneumocephalus after endoscopic sinus and microscopic skull base surgery

DOI:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.02.012 URL [Cited within: 1]

Post-traumatic delayed intracerebral tension pneumatocele: a case report and review of literature

Incidence and management of tension pneumocephalus after anterior craniofacial resection: case reports and review of the literature

DOI:10.1053/hn.1999.v120.a83901 URL [Cited within: 1]

Post traumatic tension pneumocephalus: the Mount Fuji Sign

PMID:28665089

[Cited within: 1]

Pneumocephalus is defined as the presence of intracranial air. This is most commonly secondary to a traumatic head injury. Tension pneumocephalus presents radiologically with compression of the frontal lobes and widening of the interhemispheric space between the frontal lobes. It is often termed the Mount Fuji sign due to a perceived similarity with an iconic mountain peak in Japan. We present the case of a 52-year-old gentleman who presented to the emergency department shortly before 8am on a Saturday morning following an assault. He was alert and ambulatory with no clinical evidence of raised intracranial pressure. A plain radiograph of the facial bones showed significant pneumocephalus. A later CT was consistent with a tension pneumocephalus which usually necessitates urgent decompression.The patient showed no clinical signs or symptoms of raised intracranial pressure and was managed conservatively. He was discharged home 16 days later with no neurological deficit.

Traumatic tension pneumocephalus - two cases and comprehensive review of literature

DOI:10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_8_17 URL [Cited within: 1]

Posttraumatic tension pneumocephalus

DOI:10.1097/00001199-199902000-00009 URL [Cited within: 1]

An unusual case of infective pneumocephalus: case report of pneumocephalus exacerbated by continuous positive airway pressure