INTRODUCTION

The disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been named coronavirus disease (COVID-19) by World Health Organization (WHO).[1,2,3] Thus far, the COVID-19 has been spreading quickly, and almost all countries and regions around the world have been affected.[4-6] WHO has declared the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020.[7]

The influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus causes seasonal epidemics that result in severe illnesses and deaths almost every year in China.[8] Coincidentally, it was found clinically that a few patients were diagnozed with both COVID-19 and influenza virus in China.[9] In light of this, there is an urgent need to distinguish COVID-19 characteristics from H1N1, which may play an important role in clinical practice.

This study aims to compare the epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics between patients with COVID-19 and H1N1, and to develop a differentiating model and a simple scoring system.

METHODS

Study design and participation

For this single-center retrospective study, we recruited COVID-19 patients with age >14 years from January 18 to February 28, 2020 and H1N1 patients from December 21, 2009 to February 5, 2010 who visited the fever clinics in the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. The requirement for informed patient consent was waived by the ethics committee.

Definitions

A confirmed case was defined as a positive result of SARS-CoV-2 or H1N1 pdm09 on real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay of nasal and pharyngeal swab specimens.

Data collection

Data, including age, gender, COVID-19 related exposure history, clinical symptoms and signs, coexisting illness, laboratory findings, and radiologic changes on admission, were collected. Computed tomography (CT) and all laboratory tests were performed according to the clinical care needs of each individual patient.

Laboratory assessments included complete blood count, blood chemical analysis, coagulation testing, liver and renal functions, electrolytes, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), lactate dehydrogenase, and creatine kinase. To ensure the accuracy of diagnosis, a consultant radiologist, a member of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital expert group for COVID-19, was arranged to review all CT scan images.

Virological investigations

Nasal or nasopharyngeal swab samples were obtained when the patient visited the fever clinic, and the test for SARS-CoV-2 was performed at the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays were performed following the protocol established by the WHO.[10]

H1N1 pdm09 virus was detected by real-time RT-PCR assay that used fluorogenic hydrolysis probe technology. The real-time RT-PCR assays were in accordance with the protocol from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended by the WHO. The manufacturer’s protocol (Roche) was followed.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (%), and continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR). To compare variables between groups, the non-parametric comparative test and χ2 test were used for continuous data and categorical data, respectively. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using the significant differentiating factors (P<0.05) between COVID-19 patients and H1N1 patients. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) was calculated by constructing logistic regression models of two different variable sets (clinical and laboratory). Age and gender were initially entered into these models. For each model, the variables that did not meet the significance level of likelihood ratio test (P>0.05) were removed by reverse elimination until all the unimportant variables were removed. The remaining significant variables from each of the two initial models were then entered into a final multivariate logistic regression model. Insignificant variables were again removed by backward stepwise elimination. In the final multivariate logistic regression model, the scoring model was matched with the weight of age as 1, and the scores were allocated to the remaining variables according to their logical OR. When an adjusted OR was less than 1, the best cut-off was less than or equal to the cut-off point, and the score was the reciprocal of adjusted OR, with scores rounded. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was constructed for the scoring model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 21.0 software.

RESULTS

Clinical features and severity of illness

A total of 236 patients were enrolled, including 20 patients with COVID-19 and 216 patients with H1N1. The most commonly reported symptoms of H1N1 patients were fever (100%), sore throat (54%), sputum production (51%), myalgia (51%), chilly (50%), headache (43%). The symptoms of COVID-19 patients included fever (80%), cough (35%), and sore throat (25%). Compared with H1N1 patients, COVID-19 patients were significantly older in age (26 years vs. 59 years, P<0.001) with those between 60 and 69 years being more common (3/216 vs. 10/20, P<0.001), while patients’ age under 39 years (185/216 vs. 6/20, P<0.001) were more common in H1N1 patients. H1N1 patients were more likely to have fever (100% vs. 80%, P<0.001) and chilly (50% vs. 5%, P<0.001). Additionally, upper respiratory symptoms were more common in H1N1 patients, including nasal congestion (29% vs. 0%, P=0.003), sneeze (12% vs. 0%, P<0.001), rhinorrhea (39% vs. 0%, P<0.001), sore throat (54% vs. 25%, P=0.018), and sputum production (51% vs. 25%, P=0.034). For some vital signs, COVID-19 patients had lower heart rate (86 beats/minute vs. 106 beats/minute, P<0.001) and body temperature (37.3 ℃ vs. 38.5 ℃, P<0.001), higher respiratory rate (20 breaths/minute vs. 20 breaths/minute, P=0.024) and systolic pressure (126.5 mmHg vs. 119 mmHg, P=0.013, 1 mmHg=0.133 kPa) compared with H1N1 patients. The indicators regarding severity assessment, such as Confusion, Uremia, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure and age 65 years (CURB-65) score, and quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score between COVID-19 patients and H1N1 patients were comparable (all P>0.05); however, COVID-19 patients were more likely to develop pneumonia (75% vs. 14%, P<0.001) and longer in time from symptom onset to hospitalization (1 day vs. 5 days, P<0.001). The prevalence of chronic cardiovascular disease (35% vs. 1%, P<0.001) was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 than in those with H1N1. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the underlying medical conditions.

Laboratory findings

Compared with H1N1 patients, COVID-19 patients had lower leukocyte counts (6.495×109/L vs. 4.215×109/L, P<0.001), lower ratios and counts of neutrophil (ratio 0.743 vs. 0.615, P=0.001; counts 4.76×109/L vs. 2.86×109/L, P<0.001) and basophilic granulocyte (ratio 0.003 vs. 0.002, P=0.032; counts 0.02×109/L vs. 0.01×109/L, P=0.001), and a higher ratio of lymphocyte (0.173 vs. 0.235,P=0.001). Compared with H1N1 patients, levels of hemoglobin (135.5 g/L vs. 148 g/L, P=0.005) and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR, 1.38 vs. 1.86, P=0.036) were higher in COVID-19 patients, while neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR, 5.31 vs. 2.67, P<0.001) and platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR, 212.74 vs. 164.37, P=0.023) were lower. As for liver and renal functions, patients’ lactate dehydrogenase (199 U/L vs. 144 U/L, P<0.001) was higher and creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme (CK-MB, 4.0 U/L vs. 10.7 U/L, P<0.001) was lower in COVID-19 patients than in H1N1 patients.

Independent differentiating factors of COVID-19 in suspected COVID-19 patients

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for identifying the risk factors of SARS-CoV-2. The ROC curve analysis was used to distinguish the best cut-off value of these factors. The significant variables that remained in favor of SARS-CoV-2 infection were age >34 years (adjusted OR 1.167, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.077-1.264), temperature >37.5 °C (adjusted OR 0.054, 95%CI 0.009-0.314), no sputum (adjusted OR 12.591, 95% CI 1.412-112.305), without myalgia (adjusted OR 19.318, 95% CI 1.480-252.214), lymphocyte ratios ≥20% (adjusted OR 117.372, 95% CI 1.825-165.330) and CK-MB >9.7 U/L (adjusted OR 1.091, 95% CI 1.033-1.152), which were independent differentiating factors. Each of these variables was scored according to its OR (Table 1). The sum of the scores was the total score of predicted COVID-19.

Table 1 Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for significant features of COVID-19

| Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | P-value | AdjustedOR | 95% CI for OR | Scorea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| Age | 0.154 | 0.041 | 14.277 | <0.001 | 1.167 | 1.077 | 1.264 | 1 |

| Temperature | -2.923 | 0.901 | 10.529 | 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.009 | 0.314 | -19 (-1/0.054) |

| No sputum | 2.533 | 1.116 | 5.147 | 0.023 | 12.591 | 1.412 | 112.305 | 13 |

| Without myalgia | 2.961 | 1.311 | 5.102 | 0.024 | 19.318 | 1.480 | 252.214 | 19 |

| Lymphocyte ratio ≥20% | 2.855 | 1.150 | 6.167 | 0.013 | 17.372 | 1.825 | 165.330 | 17 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 0.087 | 0.028 | 9.692 | 0.002 | 1.091 | 1.033 | 1.152 | 1 |

| Constant | 96.512 | 32.033 | 9.078 | 0.003 | ||||

a: a positive score favors COVID-19; CK-MB: creatine kinase-myocardial band isoenzyme; S.E.: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

A regression equation model of predicted probability was established, including the only independent risk factor, as follows:

Y=1/(1+e0.172×age-2.947×temperature+2.410×sputum production+2.609×myalgia+105.654 )

(without sputum production, sputum production=0; with sputum production, sputum production= -1; without myalgia, myalgia=0; with myalgia, myalgia= -1)

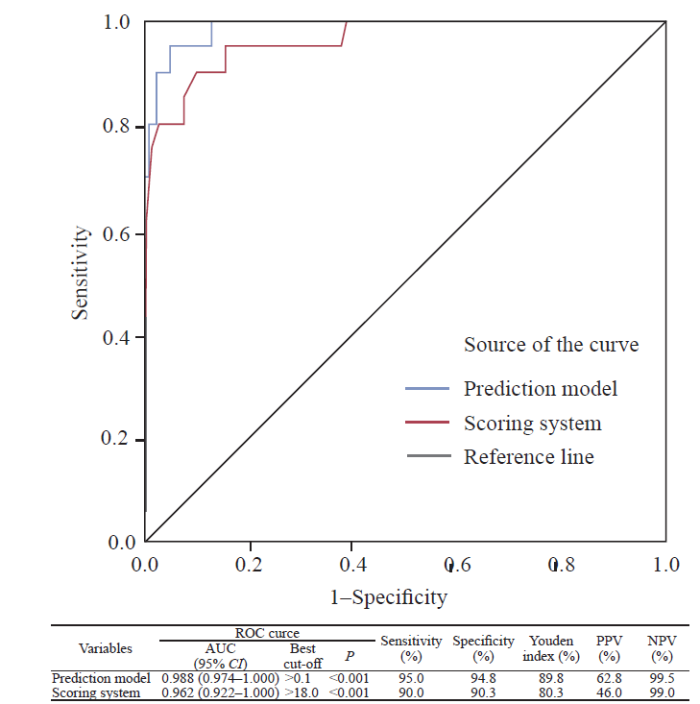

Differentiating performance of the prediction model and scoring system for COVID-19

The area under curves (AUCs) of the prediction model and scoring system in differentiating COVID-19 patients from H1N1 were 0.988 (0.974-1.000) (cut-off value >0.1, sensitivity=95.0%, specificity=94.8%) and 0.962 (0.922-1.000) (cut-off value >18.0, sensitivity=90.0%, specificity=90.3%), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ROC analyses of the model prediction probability and scoring system for differentiating COVID-19. PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; AUC: area under curve.

DISCUSSION

Our study retrospectively analyzed H1N1 patients in the Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital diagnosed from 2009 to 2010 and COVID-19 patients diagnosed in 2020. We presented the differences between the early clinical features and laboratory findings of both diseases. Besides, we have formulated a simple scale to distinguish the above two kinds of infectious diseases in order to better clinically identify and treat patients with related infections.

Similarities of clinical features between COVID-19 and H1N1 have been earlier noted.[9] The present findings showed that there was no significant difference in the severity of the disease between the two groups by two clinical scores; however, the proportion of pneumonia in the COVID-19 group was significantly higher than that in the H1N1 group. Patients in the two groups mainly presented with fever, sore throat, and cough. However, very few patients with COVID-19 infection had symptoms as chilly, nasal congestion, sneeze, rhinorrhea, headache, or myalgia, indicating that the target cells may be located in the lower airway. This may be related to the difference in binding sites between the two viruses and their receptors.[11,12,13] It has been speculated that COVID-19 infected human respiratory epithelial cells through the spike protein on the outer surface of the virus and the mediation of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptors on the surface of human cells.[14] Of note, ACE2 is expressed at higher levels in the lungs of the elderly,[15] which may offer an explanation on why older people are more vulnerable to be infected with COVID-19. Patients with COVID-19 have a lower heart rate than those with H1N1, which may reflect differences in body temperature rather than the severity of pneumonia. It remains uncertain if there is any difference in heart damage between the two viruses. Results of the multivariate analysis indicated that sputum and myalgia were more common in H1N1 patients, which was not completely consistent with Tang’s report.[16]

For laboratory findings, we found that lymphopenia and low lymphocyte ratio were common not only in COVID-19 patients but also in H1N1 patients, as well as a reduced number of basophils, a feature that was consistent with most current clinical studies.[2-3,17-19] Interestingly, the lymphocyte ratio of COVID-19 patients was significantly higher than that of H1N1 patients. The difference may be attributed to the higher neutrophils in the H1N1 group. However, there was no statistical difference in lymphocyte counts between the two groups. We found that the number of basophils of COVID-19 patients was significantly lower than that of H1N1 patients, but the reason was still unclear. The NLR, PLR, and LMR, as immune and infection-related biomarkers, had been widely reported in tumors and other infectious diseases;[20,21,22] increases in NLR and MLR in COVID-19 patients often indicate impaired immune function and can predict progression.[18,23-24] In the current study, NLR and PLR were elevated in both groups, but higher in H1N1 patients than in COVID-19 patients. However, in our cohort, patients of the two groups were equally severe, even more severe in COVID-19 patients. In other words, the difference between the two groups may not be due to the severity of the disease, but to the different pathogenesis of the two viruses. The lung and the immune system are the main targets that the two viruses attack. From our data, the proportion of pneumonia was significantly higher in the COVID-19 group than in the H1N1 group, so we speculated that SARS-CoV-2 may be more prone to the lungs, while H1N1 pdm09 virus to the immune system.

In addition, H1N1 patients had higher serum creatinine levels but lower CK-MB levels. This suggests that H1N1 pdm09 may be more likely to damage the kidney, but the effect on the heart was not as much as that of the COVID-19. A recent study[25] reported that pericytes with high expression of ACE2 might act as the target cardiac cell of SARS-CoV-2. The pericytes injury due to virus infection may result in capillary endothelial cells dysfunction, inducing microvascular dysfunction. It is interesting to note that patients with basic heart failure disease showed increased ACE2 expression at both mRNA and protein levels. This may be one reason why COVID-19 had a higher proportion of basic chronic cardiovascular disease and a higher level of CK-MB in our cohort.

Finally, we comprehensively analyzed the clinical characteristics and laboratory findings, and screened out six differentiating factors for COVID-19: age >34 years, temperature ≤37.5 ℃, no sputum or myalgia, lymphocyte ratio ≥20% and CK-MB >9.7 U/L. Besides, based on the OR of each factor in the regression model, we weighted each factor and developed a scoring scale, in which a patient with a score >18 was very likely to diagnose COVID-19. At present, viral nucleic acid detection may still be the most effective method to distinguish between different pathogen infections;[26,27] however, there is a certain false negative in nucleic acid detection, and there is a shortage of detection reagents in the outbreak of infectious disease. Although COVID-19 shares many similarities with H1N1, it has its own characteristics. In the present study, the developed prediction model and scoring system both have good differentiating performance. The clinical model scores based on the clinical features of H1N1 and COVID-19 may be a good complement to the clinical diagnosis. Meanwhile, in areas where two diseases coexist, the simple scoring system may be useful to identify patients with certain features. This strategy of hierarchical treatment of patients can relieve strained medical resources, especially during outbreaks of infectious disease.

This study analyzed and compared the differences between the COVID-19 and H1N1 among non-critical patients in the fever clinic. However, the current study had some limitations. Firstly, this was a single-center study, and the data for the two groups were not from the same period. In view of this, the applicability of our findings may vary depending upon the relative prevalence of the etiological agent during any particular period. Secondly, the majority of patients in the two groups were mild patients, and their clinical characteristics and laboratory data may not be applicable to patients with severe infection. Thirdly, CT imaging diagnosis is one of the important methods of the COVID-19.[28,29] However, the radiological assessment of influenza cases in 2009 was not as good as that of patients with COVID-19 in 2020. Therefore, we did not explore in depth in imaging. Finally, the power of the study was limited because of a small sample size; and the clinical data were incomplete, such as lack of CRP, PCT, and other inflammatory indicators.

CONCLUSIONS

The present results indicate that there are clinical and laboratory differences between COVID-19 and H1N1. Compared with H1N1, COVID-19 patients are older, no sputum or myalgia, lymphocyte ratio ≥20%, and CK-MB >9.7 U/L. The prediction model and scoring system based on these independent discriminant factors have a good differentiating performance. It may be a useful tool to identify patients who need further tests for SARS-CoV-2 and immediate medical isolation. However, it is of paramount importance to consider the epidemiological situation in each country and region when applying this model.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors: WQJ, XSL, and WHZ contributed equally to this paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Reference

A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019

DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 URL [Cited within: 1]

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 URL [Cited within: 2]

Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 URL [Cited within: 2]

First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States

DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191 URL [Cited within: 1]

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and prosthetic heart valve: an additional coagulative challenge

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2020.04.009 URL

The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview

DOI:10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270 URL [Cited within: 1]

WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic

DOI:10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

PMID:32191675

[Cited within: 1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020, has declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic (1). At a news briefing, WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, noted that over the past 2 weeks, the number of cases outside China increased 13-fold and the number of countries with cases increased threefold. Further increases are expected. He said that the WHO is "deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity and by the alarming levels of inaction," and he called on countries to take action now to contain the virus. "We should double down," he said. "We should be more aggressive." [...].

Antigenic patterns and evolution of the human influenza A (H1N1) virus

DOI:10.1038/srep14171

PMID:26412348

[Cited within: 1]

The influenza A (H1N1) virus causes seasonal epidemics that result in severe illnesses and deaths almost every year. A deep understanding of the antigenic patterns and evolution of human influenza A (H1N1) virus is extremely important for its effective surveillance and prevention. Through development of antigenicity inference method for human influenza A (H1N1), named PREDAC-H1, we systematically mapped the antigenic patterns and evolution of the human influenza A (H1N1) virus. Eight dominant antigenic clusters have been inferred for seasonal H1N1 viruses since 1977, which demonstrated sequential replacements over time with a similar pattern in Asia, Europe and North America. Among them, six clusters emerged first in Asia. As for China, three of the eight antigenic clusters were detected in South China earlier than in North China, indicating the leading role of South China in H1N1 transmission. The comprehensive view of the antigenic evolution of human influenza A (H1N1) virus can help formulate better strategy for its prevention and control.

The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China

DOI:10.1002/jmv.v92.9 URL [Cited within: 2]

Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease

DOI:10.1038/labinvest.3700656 URL [Cited within: 1]

Receptor-binding specificity of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus determined by carbohydrate microarray

DOI:10.1038/nbt0909-797 URL [Cited within: 1]

Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation

DOI:10.1126/science.abb2507 URL [Cited within: 1]

Addendum: a pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin

DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z URL [Cited within: 1]

Organ-protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its effect on the prognosis of COVID-19

DOI:10.1002/jmv.25785

PMID:32221983

[Cited within: 1]

This article reviews the correlation between angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and severe risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the possible mechanisms. ACE2 is a crucial component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). The classical RAS ACE-Ang II-AT1R regulatory axis and the ACE2-Ang 1-7-MasR counter-regulatory axis play an essential role in maintaining homeostasis in humans. ACE2 is widely distributed in the heart, kidneys, lungs, and testes. ACE2 antagonizes the activation of the classical RAS system and protects against organ damage, protecting against hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Similar to SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 also uses the ACE2 receptor to invade human alveolar epithelial cells. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a clinical high-mortality disease, and ACE2 has a protective effect on this type of acute lung injury. Current research shows that the poor prognosis of patients with COVID-19 is related to factors such as sex (male), age (>60 years), underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease), secondary ARDS, and other relevant factors. Because of these protective effects of ACE2 on chronic underlying diseases and ARDS, the development of spike protein-based vaccine and drugs enhancing ACE2 activity may become one of the most promising approaches for the treatment of COVID-19 in the future.© 2020 The Authors. Journal of Medical Virology published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Comparison of hospitalized patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19 and H1N1

DOI:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.032 URL [Cited within: 1]

Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China

DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa0906612 URL [Cited within: 1]

Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China

DOI:10.1093/cid/ciaa248 URL [Cited within: 1]

Laboratory features throughout the disease course of influenza A (H1N1) virus infection

Prediction of progression-free survival in patients with advanced, well-differentiated, neuroendocrine tumors being treated with a somatostatin analog: the GETNE-TRASGU study

DOI:10.1200/JCO.19.00980

PMID:31390276

[Cited within: 1]

Somatostatin analogs (SSAs) are recommended for the first-line treatment of most patients with well-differentiated, gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine tumors; however, benefit from treatment is heterogeneous. The aim of the current study was to develop and validate a progression-free survival (PFS) prediction model in SSA-treated patients.We extracted data from the Spanish Group of Neuroendocrine and Endocrine Tumors Registry (R-GETNE). Patient eligibility criteria included GEP primary, Ki-67 of 20% or less, and first-line SSA monotherapy for advanced disease. An accelerated failure time model was developed to predict PFS, which was represented as a nomogram and an online calculator. The nomogram was externally validated in an independent series of consecutive eligible patients (The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom).We recruited 535 patients (R-GETNE, n = 438; Manchester, n = 97). Median PFS and overall survival in the derivation cohort were 28.7 (95% CI, 23.8 to 31.1) and 85.9 months (95% CI, 71.5 to 96.7 months), respectively. Nine covariates significantly associated with PFS were primary tumor location, Ki-67 percentage, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, alkaline phosphatase, extent of liver involvement, presence of bone and peritoneal metastases, documented progression status, and the presence of symptoms when initiating SSA. The GETNE-TRASGU (Treated With Analog of Somatostatin in Gastroenteropancreatic and Unknown Primary NETs) model demonstrated suitable calibration, as well as fair discrimination ability with a C-index value of 0.714 (95% CI, 0.680 to 0.747) and 0.732 (95% CI, 0.658 to 0.806) in the derivation and validation series, respectively.The GETNE-TRASGU evidence-based prognostic tool stratifies patients with GEP neuroendocrine tumors receiving SSA treatment according to their estimated PFS. This nomogram may be useful when stratifying patients with neuroendocrine tumors in future trials. Furthermore, it could be a valuable tool for making treatment decisions in daily clinical practice.

Baseline derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic biomarker for non-colorectal gastrointestinal cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade

DOI:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108345 URL [Cited within: 1]

Impact of bronchial colonization with Candida spp. on the risk of bacterial ventilator-associated pneumonia in the ICU: the FUNGIBACT prospective cohort study

DOI:10.1007/s00134-019-05622-0 URL [Cited within: 1]

Predictors for imaging progression on chest CT from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients

COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy

DOI:10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3 URL [Cited within: 1]

The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2

DOI:10.1093/cvr/cvaa078 URL [Cited within: 1]

Headache may not be linked with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2020.04.014 URL [Cited within: 1]

Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR

Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on CT scan vs RT-PCR: reflecting on experience from MERS-CoV

DOI:S0195-6701(20)30100-6 PMID:32147407 [Cited within: 1]

Clinical features and chest CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a single-center study in Shanghai, China

DOI:10.2214/AJR.20.22959 URL [Cited within: 1]