Dear editor,

The incidence of emergency department (ED) visits from gastroparesis and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome has increased by two folds over the past decade.[1,2,3] Roldan et al[4] reported that patients with these conditions often have prolonged ED stays and are likely to be hospitalized because of the danger of dehydration and challenges inherent in relieving symptoms. Opioid analgesia is a particularly troublesome treatment modality; these conditions are often chronic with frequent recurrences, and repeated opiate therapy can cause opioid dependency and narcotic bowel syndrome.[5] Haloperidol (HP) and droperidol, members of the butyrophenone class, have potent antidopaminergic activity in the chemoreceptor trigger zone.[6,7] Intramuscular administration of HP is being used increasingly in the ED to treat nausea, vomiting secondary to gastroparesis,[6] intractable vomiting,[8] and cyclical vomiting.[9,10]

Patients with intractable vomiting come to EDs seeking symptom relief. Unless they have an established pre-existing diagnosis, the emergency physician has the difficult task of treating symptoms and identifying ailment causes. Many physicians have turned to intravenous (IV) HP over its intramuscular counterpart to manage intractable vomiting[11] as IV HP has a superior onset of action between 3 and 20 minutes. Interestingly, the use of IV HP persists even despite current United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommendations cautioning the use of IV HP. The HP injection is not approved for IV administration. If HP is administered intravenously, the electrocardiogram (ECG) should be monitored for QT prolongation and arrhythmias.[12,13] HP's most effective dose and administration route have not been well established in patients with undifferentiated intractable vomiting.

This study is designed to determine the efficacy of IV HP in reducing hospitalization rates for patients with undifferentiated intractable vomiting, cyclical vomiting, as well as gastroparesis.

METHODS

This retrospective case-control cross-over study used the electronic medical record to analyze visits between October 2013 and March 2018 at an urban community ED with approximately 42,000 visits per year. All patients with a final ED diagnosis of intractable vomiting, cyclical vomiting, or gastroparesis were selected initially. Patients were diagnosed with intractable vomiting and cyclical vomiting as a final diagnosis by a treating ED physician. Patients with gastroparesis either had verbally confirmed to the physician their pre-existing diagnosis or had gastroparesis confirmed on a prior inpatient stay with a gastric emptying study.

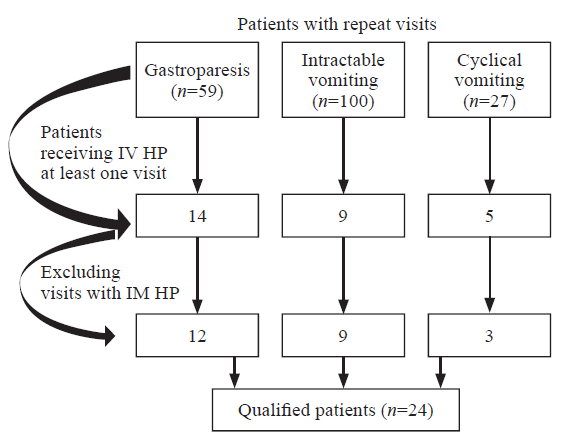

Patients met inclusion criteria if they had two or more ED visits for the treatment of intractable vomiting, cyclical vomiting, or gastroparesis and did not receive HP (non-IV HP) during one visit but did receive it during a previous or subsequent visit (Figure 1). For patients who made multiple visits, the earliest visit fulfilling the inclusion criteria was selected. We planned to exclude visits occurring within seven days of each other to ensure discrete illness events, but there were no instances requiring this exclusion.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cohort and inclusion criteria. HP: haloperidol; IV: intravenous; IM: intramuscular.

Our search criteria yielded 24 eligible patients (48 total patient encounters) over the 4.5-year study period. Two independent trained reviewers (medical students) collected the data. No discrepancies were noted by the principal investigator after independently reviewing their work.

The primary outcome of this study was hospitalization, as defined on chart review by the transition of care of the patient from the ED care to the inpatient team care, under observation or inpatient status. Secondary outcomes of interest were opioid analgesic administration calculated using morphine equivalent doses of analgesia (http://www.medcalc.com/narcotics.html), the intensity of abdominal pain recorded on a scale of 1 to 10 at triage and at time of disposition, and ED length of stay. Dosing of IV HP and any adverse events were recorded. We noted if additional medications were administered as well as the sequence in which they were administered.

An incomplete pain score charting was noted in three out of 24 patients. The length of stay could not be determined accurately in one out of 24 patients.

Descriptive statistics, Fisher's exact test, and McNemar test were used for comparison of categorical variables, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variable comparison was performed. Statistical significance was defined as two-tail P-values less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS and R statistical packages.

RESULTS

The majority of patients in this study were between the ages of 31 and 40 years. Of the 24 patients, 19 (79.2%) required hospitalization during the visit in which they did not receive HP, whereas eight (33.3%) required hospitalization during the visit in which they were given IV HP (Table 1). The outcome of reduced hospitalization rate in the IV HP group was prominent (odds ratio [OR] 0.083, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.002-0.563, P=0.004). Further subgroup evaluation demonstrated a trend amongst the gastroparesis group receiving IV HP for decreased hospitalization rate.

Table 1 Hospitalization rate comparison between the non-IV HP group and the IV HP group

| Parameters | n | Percentage | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 24 a | ||

| Hospitalized during non-IV HP visit | 19 | 79.2% | 0.003 |

| Discharged after non-IV HP visit | 5 | 20.8% | |

| Hospitalized during IV HP visit | 8 | 33.3% | |

| Discharged after IV HP visit | 16 | 66.7% | |

| Gastroparesis | 12 a | ||

| Hospitalized during non-IV HP visit | 10 | 83.3% | 0.036 |

| Discharged after non-IV HP visit | 2 | 16.7% | |

| Hospitalized during IV HP visit | 4 | 33.3% | |

| Discharged after IV HP visit | 8 | 66.7% | |

| Cyclical vomiting | 3 a | ||

| Hospitalized during non-IV HP visit | 3 | 100.0% | 0.100 |

| Hospitalized during IV HP visit | 0 | 0 | |

| Intractable vomiting | 9 a | ||

| Hospitalized during non-IV HP visit | 6 | 66.7% | 0.637 |

| Discharged after non-IV HP visit | 3 | 33.3% | |

| Hospitalized during IV HP visit | 4 | 44.4 | |

| Discharged after IV HP visit | 5 | 55.6% |

a: cross-over study with total number of patients each with two visits, one visit not receiving haloperidol (non-IV HP visit) and one visit receiving haloperidol (IV HP visit); HP: haloperidol; IV: intravenous.

The median morphine equivalent analgesic dose was 7.7 mg in the non-IV HP group and 0 mg in the IV HP group. The median of the differences in analgesic dosing provided was statistically significant (-5.2, 95% CI -9.6 to -3.0, P<0.005).

The median value of pain reduction was lower in the non-IV HP group than in the IV HP group (5 vs. 7), but the difference was not statistically significant (-2.0, 95% CI -0.5 to 4.5, P=0.108). The length of stay in the ED was not significantly different between the two groups (9.8 hours in the non-IV HP group vs. 9.3 hours in the IV HP group).

The most frequently administered dose of IV HP was 5 mg, and it was typically given as a secondary agent (Table 2). No adverse side effects (dystonia, akathisia, excessive sedation, dysrhythmia, or intervention for QTc prolongation) were documented in the group that received IV HP.

Table 2 Medication classes administered, n (%)

| Groups | Antiemetic | Benzodiazepin | Opiate | Antihistamine | When haloperidol administered a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-IV HP group | 23 (95.8) | 8 (33.3) | 19 (79.2) | 7 (29.2) | Not applicable |

| IV HP group | 23 (95.8) | 8 (33.3) | 10 (41.7) | 10 (41.7) | 2 mg |

a: haloperidol as median medication administered during IV HP visit; HP: haloperidol; IV: intravenous.

DISCUSSION

HP is a butyrophenone-type antipsychotic that is available in oral and intramuscular preparations. It emerged from the pharmaceutical landscape in 1958 and was approved for entry into the USA market in 1967. It is commonly used as an antipsychotic due to its potent dopamine D2 receptor antagonist activity, which also causes it to be an effective agent in treating nausea. Over the past 40 years, it has been used extensively in psychiatry.[14] In fact, the authors of a meta-analysis comprising 21 randomized controlled trials based on more than 3,000 patient visits calculated that cardiac dysrhythmias occurred in 0.21% of cases in which a dose of 5 mg of IV HP was administered.[14] A precautionary ECG prior to IV HP administration as well as continuous cardiac monitoring is recommended.[15] HP use has been described in the palliative care and anesthesiology literature, being administered for intractable vomiting and postoperative vomiting, respectively, with positive outcomes.[16,17,18] In addition to its antiemetic effects, HP appears to amplify the analgesic effect of opiates. This effect is suspected for several reasons: HP synergistically augments the dopaminergic pathway in the striata niagara in the brain,[19] it has an isomeric similarity to meperidine, and it plays a role in the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) pain modulation pathway in animal models.[4]

We found significant benefits of IV HP administration in terms of fewer patients requiring hospitalization in our study. The decreased hospitalization rate was consistent with prior studies and case reports using intramuscular and IV HP.[4,6,10] In a study by Ramirez et al,[6] a cohort of 52 patients who received intramuscular HP for management of diabetes-associated gastroparesis were case-matched to a prior ED visit when they had not received HP. Their study noted a reduction of hospitalization rates in their HP group of approximately 17%, while our study noted a nearly 50% reduction in hospitalization. It remains to be determined if this significant reduction in hospitalization rates is due to the IV route of HP used in our cohort, rather than the intramuscular route from Ramirez et al.[6]

Our study also noted fewer requirements for opioid analgesia. Ramirez et al[6] found that HP as an adjunctive therapy was superior to placebo for acute gastroparesis symptoms.[4] The median morphine equivalent analgesic dose was 7.7 mg in the non-IV HP group and 0 mg in the IV HP group. Also, the median reduction in pain (-2 on the pain scale), while not statistically significant, did show a moderate association. IV HP reduced analgesia requirements and appeared to have reduced pain scores in patients.

Limitations

This study's main limitation was its small sample size. Our inclusion criteria encompassed intractable vomiting, cyclical vomiting, and gastroparesis. Generally, at our clinical site, HP administration for nausea was reserved for patients with severe and intractable vomiting, which limited our ability to include patients with undifferentiated nausea and vomiting as their final diagnosis. Our study's secondary outcome of ED length of stay did not reach statistical significance. Our small sample size may have been underpowered to detect this outcome measure.

Our study design enabled us to capture repeat visits to one ED for the same gastrointestinal condition, but patients could have gone to other hospitals seeking treatment for the same condition. The study site is in a metropolitan area with a variety of secondary and tertiary hospitals, so it was possible that we did not capture all ED visits by the patients who met our inclusion criteria. Our search criteria focused on intractable vomiting and did not include other final diagnoses, such as abdominal pain. Additionally, our use of three subcategories of vomiting could have created confounding variables that were not controlled for in our retrospective analysis.

Our patient population was a demographically homogenous group, which made our results less generalizable. Our study period spanned more than four years. Although most visits were clustered over several months, there were some visits with a temporal gap of over six months.

This study was not powered to evaluate the frequency of adverse effects related to the IV administration of HP. We found no documentation of adverse events in the patients' charts, but HP's action has a half-life of 21 to 24 hours, so dystonic reactions or other adverse effects could have arisen after the typical ED course. No cardiac events occurred in either of our cohort groups.

CONCLUSIONS

In this small retrospective study, IV HP appears to be an effective adjunctive treatment in the ED for patients suffering from intractable vomiting, cyclical vomiting, or gastroparesis. HP is more effective than traditional care in reducing the hospitalization rate. Patients who receive IV HP require less narcotic pain control. Continued research is needed to compare the efficacy of intramuscular and IV administration of HP and whether the IV administration route has a superior reduction in rates of hospitalization and analgesic dosing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The manuscript was copyedited by Linda J. Kesselring, MS, ELS.

Funding: This study did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Conflicts of interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributors: BES and KKB designed the study. BES obtained approval from the IRB for the study. AJB and AL collected the data and, in conjunction with BES and KKB, wrote the first draft. BES, KKB, AJB, AL, and RCC analyzed the results and contributed to the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Reference

Emergency department burden of gastroparesis in the United States, 2006 to 2013

DOI:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000972 URL [Cited within: 1]

Emergency department treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a review

DOI:10.1097/MJT.0000000000000655 URL [Cited within: 1]

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: public health implications and a novel model treatment guideline

DOI:10.5811/westjem.2017.11.36368

PMID:29560069

[Cited within: 1]

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is an entity associated with cannabinoid overuse. CHS typically presents with cyclical vomiting, diffuse abdominal pain, and relief with hot showers. Patients often present to the emergency department (ED) repeatedly and undergo extensive evaluations including laboratory examination, advanced imaging, and in some cases unnecessary procedures. They are exposed to an array of pharmacologic interventions including opioids that not only lack evidence, but may also be harmful. This paper presents a novel treatment guideline that highlights the identification and diagnosis of CHS and summarizes treatment strategies aimed at resolution of symptoms, avoidance of unnecessary opioids, and ensuring patient safety.The San Diego Emergency Medicine Oversight Commission in collaboration with the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency and San Diego Kaiser Permanente Division of Medical Toxicology created an expert consensus panel to establish a guideline to unite the ED community in the treatment of CHS.Per the consensus guideline, treatment should focus on symptom relief and education on the need for cannabis cessation. Capsaicin is a readily available topical preparation that is reasonable to use as first-line treatment. Antipsychotics including haloperidol and olanzapine have been reported to provide complete symptom relief in limited case studies. Conventional antiemetics including antihistamines, serotonin antagonists, dopamine antagonists and benzodiazepines may have limited effectiveness. Emergency physicians should avoid opioids if the diagnosis of CHS is certain and educate patients that cannabis cessation is the only intervention that will provide complete symptom relief.An expert consensus treatment guideline is provided to assist with diagnosis and appropriate treatment of CHS. Clinicians and public health officials should identity and treat CHS patients with strategies that decrease exposure to opioids, minimize use of healthcare resources, and maximize patient safety.

Randomized controlled double-blind trial comparing haloperidol combined with conventional therapy to conventional therapy alone in patients with symptomatic gastroparesis

DOI:10.1111/acem.2017.24.issue-11 URL [Cited within: 4]

Narcotic bowel syndrome

DOI:10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30217-5 URL [Cited within: 1]

Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms (HUGS) in the emergency department

DOI:S0735-6757(17)30182-1

PMID:28320545

[Cited within: 6]

Gastroparesis associated nausea, vomiting & abdominal pain (GP N/V/AP) are common presentations to the emergency department (ED). Treatment is often limited to antiemetic, prokinetic, opioid, & nonopioid agents. Haloperidol (HP) has been shown to have analgesic & antiemetic properties. We sought to evaluate HP in the ED as an alternative treatment of GP N/V/AP.Using an electronic medical record, 52 patients who presented to the ED w/GP N/V/AP secondary to diabetes mellitus and were treated w/HP were identified. Patients who received HP were compared to themselves w/the most recent previous encounter in which HP was not administered. ED length of stay (LOS), additional antiemetics/prokinetics administered, hospital LOS, and morphine equivalent doses of analgesia (ME) from each visit were recorded. Descriptive statistics, categorical (Chi Square Test or Z-Test for proportion) and continuous (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test) comparisons were calculated. Statistical significance was considered for two tail p-values less than 0.05.A statistically significant reduction in ME (Median 6.75 [IQR 7.93] v 10.75 [IQR12]: p=0.001) and reduced admissions for GP (5/52 v 14/52: p=0.02) when HP was administered was observed. There were no statistically significant differences in ED or hospital LOS, and additional antiemetics administered between encounters in which HP was administered and not administered. No complications were identified in patients who received HP.The rate of admission and ME was found to be significantly reduced in patients with GP secondary to diabetes mellitus who received HP. HP may represent an appropriate, effective, and safe alternative to traditional analgesia and antiemetic therapy in the ED management of GP associated N/V/AP.Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The utility of droperidol in the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

DOI:10.1080/15563650.2018.1564324 URL [Cited within: 1]

Successful control of intractable nausea and vomiting requiring combined ondansetron and haloperidol in a patient with advanced cancer

DOI:10.1016/0885-3924(94)90147-3 URL [Cited within: 1]

Cannaboid hyperemesis and the cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: recognition, diagnosis, acute and long-term treatment

Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

Haloperidol parenterally for treatment of vomiting and nausea from gastrointestinal disorders in a group of geriatric patients: double-blind, placebo-controlled study

PMID:1088951

[Cited within: 1]

Twenty-eight geriatric residents of a nursing home participated in a double-blind study to compare the 12-hour therapeutic effectiveness of a single intramuscular injection (1.0 mg) of haloperidol with that of placebo for the relief of vomiting and nausea due to gastrointestinal disorders. Significantly fewer episodes of vomiting occurred in the haloperidol group than in the placebo group. Nausea also was less frequent in the haloperidol group. After four hours, symptoms recurred much more often in the placebo group. Global evaluations showed that a significantly greater number of haloperidol patients improved markedly than did those given placebo. There were no clinically significant changes in vital signs throughout the study in the haloperidol group. In 1 placebo patient the pulse rate was significantly increased; otherwise no adverse reactions were reported for this group. Thus, in a nursing-home population of geriatric patients who experienced vomiting and nausea due to gastrointestinal disorders, haloperidol administered parenterally proved to be a safe and highly effective antiemetic agent.

Food and Drug Administration

The FDA extended warning for intravenous haloperidol and torsades de pointes: how should institutions respond?

Is low-dose haloperidol a useful antiemetic?: a meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trials

DOI:10.1097/00000542-200412000-00028 URL [Cited within: 2]

Haloperidol versus ondansetron for treatment of established nausea and vomiting following general anesthesia: a randomized clinical trial

DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001723 URL [Cited within: 1]

The efficacy of haloperidol in the management of nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer

DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.321 URL [Cited within: 1]

Novel treatments for cyclic vomiting syndrome: beyond ondansetron and amitriptyline

PMID:27757817

[Cited within: 1]

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder that is characterized by episodic nausea and vomiting. Initially thought to only affect children, CVS in adults was often misdiagnosed with significant delays in therapy. Over the last decade, there has been a considerable increase in recognition of CVS in adults but there continues to be a lack of knowledge about management of this disorder. This paper seeks to provide best practices in the treatment of CVS and also highlight some novel therapies that have the potential in better treating this disorder in the future. Due to the absence of randomized control trials, we provide recommendations based on review of the available literature and expert consensus on the therapy of CVS. This paper will discuss prophylactic and abortive therapy and general measures used to treat an episode of CVS and also discuss pathophysiology as it pertains to novel therapy. Recent recognition of the association of chronic marijuana use with cyclic vomiting has led to the possibility of a new diagnosis called "Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome," which is indistinguishable from CVS. The treatment for this purported condition is abstinence from marijuana despite scant evidence that marijuana use is causative. Hence, this review will also discuss emerging data on the role for the endocannabinoid system in CVS and therapeutic agents targeting the endocannabinoid system, which offer the potential of transforming the care of these patients.

A comparison of narcotic analgesics with neuroleptics on behavioral measures of dopaminergic activity

PMID:238089 [Cited within: 1]