Dear editor,

Chest pain is a frequent complaint of patients presenting to the emergency department (ED), and many of them are referred to the cardiology service for further investigation. At the Charles V. Keating Emergency and Trauma Centre in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 4,800 (6.6%) of the approximately 73,000 patients per year register with a complaint of “chest pain”, and 20% of patients are referred to cardiology. Coagulation studies, specifically international normalized ratio (INR) frequently part of the “routine” panel of blood tests, are ordered for patients in the ED being investigated or treated for chest pain suspected to be cardiac in nature. Recent calls to examine how much of our practice is likely to benefit patients in any way have led us to question the clinical utility of routine use of these tests.

METHODS

This retrospective ED chart review involved a sub-analysis of 1,000 patients referred to cardiology for the investigation of chest pain. The primary study was designed to investigate the use of routine chest X-ray in this population and patients were excluded if they had a requirement for chest X-ray (apart from a history of non-traumatic chest pain), as defined by nine of the ten described by Rothrock et al[1] (temperature ≥38 ℃, oxygen saturation <90%, respiratory rate >24 breaths/minute, hemoptysis, rales, diminished breath sounds, a history of alcohol abuse, tuberculosis, or thromboembolic disease). We included patients with the criterion of “age ≥60 years” as age was neither a “disease” nor an abnormal clinical variable, and excluding them would not only lead to the inference that older age is an indicator for “routine” ED screening, but also consider that many of our patients fall into this category and would also decrease the potential for reducing the number of routine ED tests.

For this sub-study investigating the utility of routine INR testing in this group, only patients with INR testing were included. In consideration that it might be reasonable to order INR tests on patients known to be on warfarin, patients that had information in their ED clinical record indicating current warfarin use were further excluded.

Chart audits were conducted according to the recommendations of Gilbert et al[2] with intensive instruction of abstractors into specific and explicit abstraction protocols, defining important variables precisely. Abstractors were trained on a set of “practice” ED medical records before the start of the study, in order to ensure the accuracy of the data gathered and the consistency in which clinical details were recorded. Frequent meetings were held with the abstractors and study coordinators to resolve disputes and review coding rules. Abstractors were blinded as to the hypothesis being tested (i.e., whether the tests were helpful to patient care or not). To reduce the incidence of transcription errors, data were entered directly (concurrent with abstraction) into a computerized data abstraction form developed by the Dalhousie Emergency Database Manager. We have used this process successfully in two previous ED studies.[3,4]

Data abstracted from the ED chart included vital signs, risk factors for ischemic cardiac disease, prior medical history, chest X-ray findings, and clinical findings. Clinical details and INR results on the database were reviewed independently by four experienced ED faculty (average 25.5-year experience, range 18-37 years). Reviewers were instructed to consider an INR result as “relevant” if they would like to know the particular result when managing a patient not on warfarin therapy with chest pain.

The medical records (beyond the details abstracted from the ED chart) of patients with positive results were examined by one investigator (SGC) to determine if there was a reason for the result that had not been recorded in the ED chart.

RESULTS

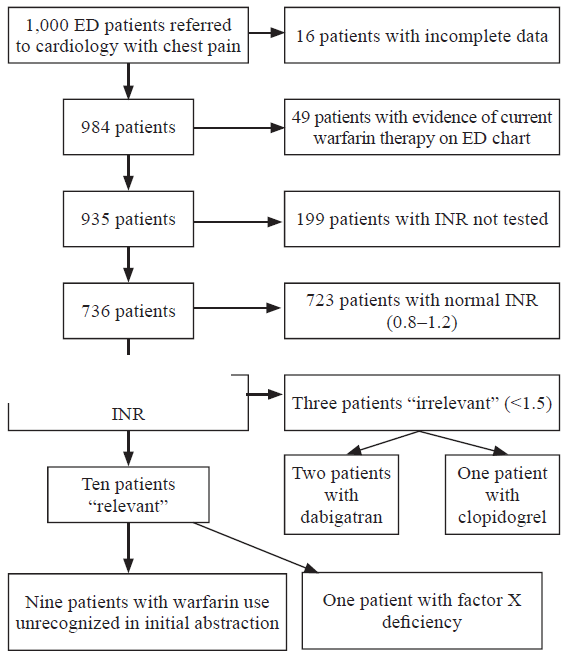

Of 1,000 patients identified for review in the original study, clinical data were available for 984 (98.4%). A total of 49 patients were excluded because the abstractors had found evidence of current warfarin therapy on the ED chart, leaving 935 patients for review. Of these, INR was measured in 736 (78.7%) patients. Thirteen patients had abnormal INR results (INR >1.2). Although no INR findings were found by any of the reviewers to contribute to the emergency care of these patients, every one of the ten cases (INR >1.5) was considered potentially “relevant” by any one of the reviewers; the three cases in which the INR was 1.3 were considered “irrelevant”.

Subsequent depth review of the complete medical records of patients with abnormal results revealed that of the results considered “relevant” in nine cases, the active use of warfarin by the patient had not been recorded in the ED chart, and one patient had a known coagulation anomaly (factor X deficiency), which was not listed as one to be screened for in the abstractors' protocol. Of the three remaining abnormal results, that were considered “irrelevant” by the reviewers, all three were on other anticoagulants (two dabigatran and one clopidogrel). A flow chart depicting how patients were analyzed is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing how patients were evaluated.

DISCUSSION

In the patient population studied, there were no INR results that led to a change in therapy, and when corrected for incomplete ED recording of current medication and omission of congenital coagulation abnormalities by the abstraction process, no results were unexpected or relevant. Our results were very similar to those of previous investigators.[5,6]

Unnecessary application of medical care is of significant current interest. The Choosing Wisely campaign, released in the USA in 2012[7] and in Canada in 2014,[8] aims to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and truly necessary.[9]

The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians released ten specialty specific recommendations.[10] The basic premise of choosing wisely, however, is far larger than groups of recommendations; it is a call for healthcare providers to consider the risk benefit ratio of each test or procedure that we carry out. Whilst this idea seems intuitive, in many cases interventions have crept into routine use that occur without any thought. In fact in many EDs, panels of biochemical tests are labelled “routine” implying that their use is appropriate for all patients and without which test might be considered somehow deficient. The measuring of indicators of coagulation status is one of such tests. The INR provides a consistent way for reporting what a patient's prothrombin time (PT) ratio would have been if measured by using the primary World Health Organization International Reference reagent.[11,12] The PT will be prolonged if the concentration of any of the tested factors is 10% or more below normal plasma values. The prolonged PT indicates a deficiency of over 10% below normal plasma values of factors Ⅶ, Ⅹ, V, prothrombin, or fibrinogen. Causes of the deficiency include vitamin K deficiency, liver failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or the use of vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin.

Patients for whom it is felt necessary to treat or exclude acute coronary syndrome often end up treatment with anticoagulants (usually fractionated or un-fractionated heparin), and in some cases proceed to cardiac catheterization, which involves invasive vascular manipulation. Presumably these factors have led to the belief that such patients could suffer harm if they had a coagulopathy that their caregivers were unaware of, which could be avoided by routine measurement of their INR. Despite this logic researchers have not been able to support it.[5,6,12-14] In patients with liver disease, there is evidence that an abnormal INR does not expose the patient to the same risk of bleeding as that induced therapeutically.[13]

In our institution, 80% of patients with chest pain are managed by the emergency physician without cardiology consultation. In order to ensure that we were not including chest pain of obviously non-cardiac origin, we limited our study to patients with chest pain subsequently referred to cardiology. It was likely that many patients with chest pain who were not referred to cardiology had workup that included INR testing, making the potential impact of removing INR from “routine practice” far more than we demonstrated. Furthermore, although we chose to focus on this defined group of patients for whom INR tests were routinely ordered, our findings showed that the “screening” use of these tests were not likely to serve ED patients in other categories who did not have a specific emergency indication for their use. We hope that our findings will add to those of others[5,6,12-14] to remind clinicians to pause and consider the potential utility of this test before reflexively ordering it.

Although guidelines for the ordering of coagulation studies do exist,[12] changing physician practice, is as a rule, challenging.[14] In the specific case of INR testing, restricting the “routine” use of the test, in addition to removing it from recommended panels, might also be facilitated by the fact that the test requires a different (blue top) sodium citrate containing collection tube, which can be stored in a different area from other “routine” tubes, requiring a special trip, and consequently specific thought, before the blood is drawn.[12]

Limitations

This study carried the limitations common to all retrospective chart reviews. Although we tried to limit these by a strict chart abstraction process, this involved only a review of the ED chart, resulting in delayed identification of current warfarin use in nine patients where the history was found elsewhere in the patient (non-emergency) record. This finding essentially demonstrated limited history taking and/or documentation in the ED chart, but an unfortunate finding restricted to a very small proportion of cases. A further limitation was that patients were excluded if they had any of nine of the ten Rothrock criteria, which were described to limit unnecessary chest X-ray and not blood tests. While we conceded that this might lead us to miss potential savings by identifying a low utility of INR testing in patients excluded for requiring a chest X-ray, it was unlikely that patients with these criteria would be considered for a “reduced investigation” plan of action, at least at this early stage.

CONCLUSIONS

INR testing is rarely useful in the ED management of patients with cardiac-type chest pain, and its use should be restricted to those in whom coagulation abnormalities might be suspected and for whom knowledge thereof would make a difference to patient care.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the institutional ethics review board of Nova Scotia Health.

Conflicts of interest: No benefits have been received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the study.

Contributors: SGC proposed and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

Reference

High yield criteria for obtaining non-trauma chest radiography in the adult emergency department population

PMID:12359278

[Cited within: 1]

To develop a clinical decision rule for predicting significant chest radiography abnormalities in adult Emergency Department (ED) patients, a prospective, observational study was conducted of consecutive adults (>or=18 years old) who underwent chest radiography for nontraumatic complaints at an urban ED with an annual census of 85,000. The official radiologist interpretation of the film was used as the gold standard for defining radiographic abnormalities. Using predefined criteria and author consensus, patients were divided into two groups: those with clinically significant abnormalities (CSA) and those with either normal or nonclinically significant abnormalities. Chi square recursive partitioning was used to derive a decision rule. Odds ratios and kappa statistics were calculated for derived criteria. The results showed 284 (17%) of 1650 patients had clinically significant abnormal radiographs. The presence of any of 10 criteria (age >or= 60 years, temperature >or= 38 degrees C, oxygen saturation < 90%, respiratory rate > 24 breaths/min, hemoptysis, rales, diminished breath sounds, a history of alcohol abuse, tuberculosis, or thromboembolic disease) was 95% sensitive (95% CI: 92-98%) and 40% specific (95% CI: 37-43%) in detecting CSA radiographs. Positive and negative predictive values were 25% (95% CI: 23-27%) and 98% (95% CI: 96-99%), respectively. A highly sensitive decision rule for detecting clinically significant abnormalities on chest radiographs in nontraumatized adults has been developed. If prospectively validated, these criteria may permit clinicians to confidently reduce the number of radiographs in this population.

Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: where are the methods?

PMID:8599488

[Cited within: 1]

Medical chart reviews are often used in emergency medicine research. However, the reliability of data abstracted by chart reviews is seldom examined critically. The objective of this investigation was to determine the proportion of emergency medicine research articles that use data from chart reviews and the proportions that report methods of case selection, abstractor training, monitoring and blinding, and interrater agreement.Research articles published in three emergency medicine journals from January 1989 through December 1993 were identified. The articles that used chart reviews were analyzed.Of 986 original research articles that were identified, 244 (25%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 22% to 28%) relied on chart reviews. Inclusion criteria were described in 98% (95% CI, 96% to 99%), and 73% (95% CI, 67% to 79%) defined the variables being analyzed. Other methods were seldom mentioned: abstractor training, 18% (95% CI, 13% to 23%); standardized abstraction forms, 11% (95% CI, 7% to 15%); periodic abstractor monitoring, 4% (95% CI, 2% to 7%); and abstractor blinding to study hypotheses, 3% (95% CI, 1% to 6%). Interrater reliability was mentioned in 5% (95% CI, 3% to 9%) and tested statistically in .4% (95% CI, 0% to 2%). A 15% random sample of articles was reassessed by a second investigator; interrater agreement was high for all eight criteria.Chart review is a common method of data collection in emergency medicine research. Yet, information about the quality of the data is usually lacking. Chart reviews should be held to higher methodologic standards, or the conclusions of these studies may be in error.

Can we predict which patients with community-acquired pneumonia are likely to have positive blood cultures? A case control study of blood cultures in community-acquired pneumonia

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2011.04.005

PMID:25215022

[Cited within: 1]

Blood cultures (BC) are commonly ordered during the initial assessment of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), yet their yield remains low. Selective use of BC would allow the opportunity to save healthcare resources and avoid patient discomfort. The study was to determine what demographic and clinical factors predict a greater likelihood of a positive blood culture result in patients diagnosed with CAP.A structured retrospective systematic chart audit was performed to compare relevant demographic and clinical details of patients admitted with CAP, in whom blood culture results were positive, with those of age, sex, and date-matched control patients in whom blood culture results were negative.On univariate analysis, eight variables were associated with a positive BC result. After logistic regression analysis, however, the only variables statistically significantly associated with a positive BC were WBC less than 4.5 × 10(9)/L [likelihood ratio (LR): 7.75, 95% CI=2.89-30.39], creatinine >106 μmol/L (LR: 3.15, 95%CI=1.71-5.80), serum glucose<6.1 mmol/L (LR: 2.46, 95%CI=1.14-5.32), and temperature > 38 °C (LR: 2.25, 95% CI =1.21-4.20). A patient with all of these variables had a LR of having a positive BC of 135.53 (95% CI=25.28-726.8) compared to patients with none of these variables.Certain clinical variables in patients with CAP admitted to hospitals do appear to be associated with a higher probability of a positive yield of BC, with combinations of these variables increasing this likelihood. We have identified a subgroup of CAP patients in whom blood cultures are more likely to be useful.

Patients with community acquired pneumonia discharged from the emergency department according to a clinical practice guideline

PMID:15496690

[Cited within: 1]

To assess the safety of discharging patients with community acquired pneumonia (CAP) according to a clinical practice guideline.A systematic retrospective review of medical records of 867 adult patients discharged from an emergency department (ED) with CAP between 3 January 1999 and 3 January 2001. Readmission or death rates within 30 days of discharge were evaluated, using data from all local hospitals and from the provincial coroner.Of 685 patients with pneumonia severity index (PSI) scores of <91, 13 (1.9%) were readmitted and five (0.76%) died within 30 days of the ED visit. Thirty day readmission and death rates for patients with PSI >90 were 7.14% (13 of 182) and 9.34% (17 of 182), respectively.Adult patients with CAP discharged from the ED according to the recommendations of a clinical practice guideline based on the PSI have low readmission and death rates, and are generally safely managed as outpatients.

Is routine coagulation testing necessary in patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain?

DOI:10.1136/emj.2010.106526

PMID:21398250

[Cited within: 3]

Driven by the need for rapid assessment, treatment and appropriate disposition of patients in the emergency department (ED), blood tests are often performed in a protocolised fashion before full clinical assessment. The cardiologists at this institution currently insist upon a coagulation profile in each patient referred with a possible acute coronary syndrome.A retrospective cohort of 1000 consecutive patients presenting to the ED with chest pain was identified. If performed, the international normalised ratio (INR) and the activated partial thromboplastin time ratio (APTR) were retrieved for each patient. If no coagulation sample was sent from the ED, a search was performed to determine whether a sample was sent within the subsequent 24-h period by the admitting hospital team. A cause of a raised INR or APTR that could have been identified easily at initial patient assessment in the ED was sought.640 patients were identified who had coagulation tests sent from the ED as part of their assessment. Of the 592 coagulation samples successfully processed 79 were abnormal. All of these abnormal tests could have been predicted on the basis of a history of warfarin or heparin use or a history of liver disease, or were trivial enough to not preclude coronary angiography or the therapeutic use of heparin.Routine coagulation testing in adults presenting to ED with chest pain is unnecessary. This practice should be replaced by a coagulation testing policy based on an increased risk of coagulopathy due to warfarin or heparin use or a history of liver disease.

Utility of routine coagulation studies in emergency department patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes

PMID:16106775

[Cited within: 3]

Many emergency departments use coagulation studies in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes.To determine the prevalence of abnormal coagulation studies in ED patients evaluated for suspected ACS, and to investigate whether abnormal international normalized ratio/partial thromboplastin time testing resulted in changes in patient management and whether abnormal results could be predicted by history and physical examination.In this retrospective observational study, hospital and ED records were obtained for all patients with a diagnosis of ACS seen in the ED during a 3 month period. ED records were reviewed to identify patients in whom the cardiac laboratory panel was performed. Other data included demographics, diagnosis and disposition, historical risk factors for abnormalities of coagulation, ED and inpatient management, INR/PTT, platelet count and cardiac enzymes. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed.Complete data were available for 223 of the 227 patients (98.7%). Of these, 175 (78.5%) were admitted. The mean age was 64.2 years. Thirteen patients (5.8%) were diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction. Of the 223 patients, 29 (13%) and 23 (10%) had INR and PTT results respectively beyond the reference range. Seventy percent of patients with abnormal coagulation test results had risk factors for coagulation disorders. The abnormal results of the remaining patients included only a mild elevation and therefore no change in management was initiated.Abnormal coagulation test results in patients presenting with suspected ACS are rare, they can usually be predicted by history, and they rarely affect management. Routine coagulation studies are not indicated in these patients.

About choosing wisely Canada

Emergency medicine: ten things physicians and patients should question

Using the international normalized ratio to standardize prothrombin time

PMID:9260421

[Cited within: 1]

The international normalized ratio, or INR, was introduced in 1983 by the World Health Organization, or WHO, Committee on Biological Standards to more accurately assess patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. The INR mandates the universal standardization of prothrombin time. This article describes the method used to calculate INR, as well as its clinical relevance to the practice of dentistry.

What emergency physicians can do to reduce unnecessary coagulation testing in patients with chest pain

Cost-effectiveness of routine coagulation testing in the evaluation of chest pain in the ED

DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.04.012

PMID:22795414

[Cited within: 1]

Approximately 5% of all US emergency department (ED) visits are for chest pain, and coagulation testing is frequently utilized as part of the ED evaluation.The objective was to assess the cost-effectiveness of routine coagulation testing of patients with chest pain in the ED.We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients evaluated for chest pain in a community ED between August 1, 2010, and October 31, 2010. Charts were reviewed to determine the number and results of coagulation studies ordered, the number of coagulation studies that were appropriately ordered, and the number of patients requiring a therapeutic intervention or change in clinical plan (withholding of antiplatelet/anticoagulant, delayed procedure, or treatment with fresh frozen plasma or vitamin K) based on an unexpected coagulopathy. We considered it appropriate to order coagulation studies on patients with cirrhosis, known/suspected coagulopathy, active bleeding, use of warfarin, or ST-elevation myocardial infarction.Of the 740 patients included, 406 (55%) had coagulation studies ordered. Of those 406, 327 (81%) patients with coagulation studies ordered had no indications for testing. One of the 327 patients (0.31%; 95% confidence interval, 0.05%-1.7%) tested without indication had a clinically significant coagulopathy (internationalized normalization ratio >1.5, partial thromboplastin time >50 seconds), but none (0%; 95% confidence interval, 0%-1.2%) of the patients with coagulation testing performed without indication required a therapeutic intervention or change in clinical plan. The cost of coagulation testing in these 327 patients was $16780.Coagulation testing on chest pain patients in the ED is not cost-effective and should not be routinely performed.Copyright © 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Are baseline prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time values necessary before instituting anticoagulation?

PMID:8457098

[Cited within: 3]

To determine whether baseline prothrombin time (PT) or partial thromboplastin time (PTT) values provide information that is useful to the clinician before initiating anticoagulation and whether emergency physicians elicit historical information about bleeding disorders before beginning anticoagulant therapy.A three-year retrospective review of the records of 199 patients admitted through the ED with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus using a predesigned study sheet that included historical questions, baseline PT and PTT values, treatment given, timing of treatment, and underlying medical problems.University-affiliated tertiary-care hospital.Deep-vein thrombosis was the primary diagnosis in 75% of patients. Pertinent historical items were not documented in 92% to 100% of patients. Baseline PT and PTT values were obtained in 94% of patients. An elevated baseline PT was found in 26 patients, all of whom were taking warfarin. An elevated baseline PTT was found in 21 patients. These results were attributed to laboratory error (one), warfarin use (nine), heparin therapy before baseline tests (five), anticardiolipin antibodies (five, one of whom was on warfarin therapy), and unknown causes (three). Heparin therapy was not altered for any patient.Emergency physicians rarely document pertinent questions about bleeding disorders before initiating anticoagulation therapy. Baseline PT and PTT values are almost routinely obtained despite the fact that they do not alter therapy or serve as sensitive or specific screening tests. Routine baseline PT and PTT values are rarely needed before initiating anticoagulation. Eliminating such routine testing would result in significant cost savings.