INTRODUCTION

Until late 2010, emergency departments (EDs) in Croatia providing care to internal medicine (non-surgical) patients were run by internal medicine specialists (IMSs), often by physicians with non-emergency subspecialties. In general, EDs were subdivided into particular specialty services, and served as “acute clinics” with on-duty physicians rotated in and out.[1] Since joining the European Union in 2013, legislation and practice in Croatia have changed. In April 2009, the European curriculum on emergency medicine, requiring a minimum training period of five years, was approved by Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament.[2] Subsequently, a new specialization for emergency physician specialists (EPSs) was established, including trauma, neurology, pediatrics, and ultrasound training. Numerous EDs around the country shifted from specialty outpatient clinics to general EDs operated by EPSs. Compared with previous non-professional teams (who were not dedicated solely to ED work due to their numerous duties within their subspecialties, particularly in tertiary centers), EPSs tend to be more involved in structural improvements, inclined to the standardization of workup and treatment, and enthusiastic in accomplishing new ED-related skills (especially the use of ultrasound). However, a concern emerged about whether the shift to EDs run completely by EPSs would lead to unnecessary investigations due to a lack of experience. This was expected to become most obvious in radiologic examinations, which were abundant.[3,4] We hypothesized that shifting to professional ED teams would initially lead to higher rates of radiologic workup during ED visits.

METHODS

The study was conducted in the ED of a tertiary teaching University Hospital Center (UHC). The UHC is situated in a one-million-inhabitant capital, and provides emergency medical services for an urban population of approximately 350,000. There is a “no refusal” strategy for citizens outside the referral area, as well as for patients with no insurance policy. The daily turnover within the ED is approximately 300 visits in total, and 80 of them are in the internal medicine ED. The service is organized in a 24-hour shift with one physician being in charge and two additional physicians (internal medicine or subspecialty residents) helping out with examinations. A consulting cardiologist, gastroenterologist, nephrologist, and intensivist are available 24 hours every day. All workup, treatment, and admittance decisions are made by the physician in charge.

There were two enrollment periods for our study. From December 21, 2012 to January 5, 2013, 1,000 consecutive patients (“all-comers”) examined within the internal medicine ED were enrolled as group 1 (G1). During this enrollment period, all patients were examined by an IMS with at least five years of work experience. These physicians were subspecialists in different fields of internal medicine. However, they all lacked structured education in the field of emergency medicine. The second enrollment period was from December 21, 2018 to January 3, 2019, in which additional 1,000 consecutive patients were enrolled as group 2 (G2). These patients were examined by an EPS with average two years of work experience, and five-year structured training in all fields of emergency medicine including trauma, emergency anesthesia, and resuscitation. A total of 51 G1 and 41 G2 patients were excluded from the study for various reasons. A propensity score matching was performed on the remaining 1,908 patients with the following matching variables: age, sex, dyspnea, cough, fever, and chest pain as leading symptoms (matching without replacement, match tolerance: 0.005). A total of 1,816 patients (908 in each group) entered the final analysis.

All the relevant demographic data, presenting signs and symptoms, as well as the workup and outcome details, were collected from digital medical archives. During workup, chest X-rays (CXRs) were performed upon indication of the specialist in charge. There were no written protocols on CXR indications. All CXRs were re-examined by an experienced intensivist who was blinded for the findings and patient details. If an original finding did not match the re-examination finding, the CXR was assessed by an experienced radiologist, and a consensus was sought. If no consensus was reached, the experienced radiologist’s finding was used as definite.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) or medians and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as counts and frequencies. Categorical variables were analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher exact test and continuous variables by Mann-Whitney U-test. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the relation of continuous variables and the tendency to perform CXR. The method was also used to create models to determine the independent contribution of different variables on the tendency to perform CXR, and for the CXR finding to be pathological. The conditional forward stepwise approach was used. The regression results were used to generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to predict pathological findings. The optimal cut-off points were determined by using Youden’s index. Two-tailed significance tests were performed, and a P-value <0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 25 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, USA).

RESULTS

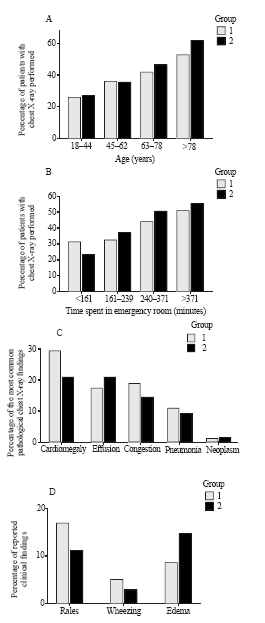

Slightly over half of the population was female (52.4%), with a mean age of 63 (45-76) years. After propensity score matching, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding age, sex, and admittance rate, frequency of chest pain, fever, dyspnea, or cough as leading symptoms. CXR was performed in 40.6% of all patients. There was no difference in the frequency of CXR (38.9% in G1 vs. 42.3% in G2, P=0.152) or abdominal X-ray (14.4% vs. 14.8%, P=0.894), while comprehensive abdominal ultrasound (6.7% vs. 3.6%, P=0.004) and computed tomography (3.9% vs. 2.0%, P=0.025) were more often performed in G1. In brief, significantly more CXRs were performed in G2 in patients older than 65 years (Figure 1A), in female patients older than 65 years, in patients presenting during the evening and night shifts (between 4 p.m. and 8 a.m.) as well as during off-hours, in patients with a history of malignancy, in patients presenting with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and in patients with bradycardia, but less in patients presenting with arrhythmia.

Overall, time spent in the ED was similar in the two groups (240 [161-371] minutes vs. 261 [154-413] minutes, P=0.198). Time spent in the ED was related to the frequency of CXR with logistic regression (odds ratio [OR]=1.115, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.087-1.144), P<0.001, Figure 1B). In the group of patients with CXR performed, time spent in the ED was longer for G2 patients (281 [185-424] minutes vs. 322 [197-496] minutes, P=0.011).

No difference in the rates of pathological CXR was found between the groups (47.3% in G1 vs. 52.2% in G2, P=0.186). The most common pathologies observed on CXR are shown in Figure 1C. The CXR finding was more often mentioned in the discharge letter in G1 (67.3% vs. 37.5%, P<0.001). This was true for both admitted (52.4% vs. 2.3%, P<0.001) and discharged patients (68.7% vs. 55.1%, P<0.001). Lung rales and wheezing were more frequently reported in the clinical status in G1, and peripheral edema in G2 patients (Figure 1D). However, when only patients with CXR signs of congestion were analyzed, no difference was found (81.5% vs. 69.1% for rales, P=0.136; 7.7% vs. 7.3% for wheezing, P=1.000). In patients with cardiomegaly, rales were more often reported in G1 (64.4% vs. 47.5%, P=0.025), while the difference in reported rates of wheezing was not significant (10.9% vs. 5.0%, P=0.183).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparisons between G1 and G2. Frequency of chest X-rays according to age (A) and time spent in the ED (B); G1 logistic regression: odds ratio (OR)=1.024, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.016-1.032; G2 logistic regression: OR=1.030, 95% CI 1.023-1.038; C: the most common pathological chest X-ray findings; D: rates of reported clinical findings.

Admittance rates were similar (23.8% vs. 22.4%, P=0.504). No difference in admittance to intensive and post-intensive care wards was detected (37.4% vs. 42.6%, P=0.317). The frequency of CXR in the two groups did not differ when the patients were stratified according to the type of ward (regular ward 61.2% vs. 67.2%, P=0.356; intensive and post-intensive care ward 50.0% vs. 57.0%, P=0.437). Among discharged patients, there were 78 repeated visits within 14 days (4.6% vs. 3.8%, P=0.355).

Antibiotics were more often prescribed in G1 (12.1% vs. 7.7%, P=0.003), and the difference persisted regardless of CXR (no CXR 8.0% vs. 4.8%, P=0.046; CXR performed 20.4% vs. 11.7%, P=0.005). On the contrary, no difference was found in prescribing diuretics at discharge, neither between the two groups in total nor when stratified against CXR.

By using binary logistic regression with 22 variables included, two models to predict the tendency to perform CXR were created (Table 1). In addition, two models to predict pathological CXR findings are presented in Table 2. By using predicted probability for pathological CXR for each case, ROC curves were plotted (G1: area under the curve 0.877±0.018, P<0.001, 95% CI 0.841-0.913, sensitivity 78.4%, specificity 82.2%; G2: area under the curve 0.785±0.023, P<0.001, 95% CI 0.740-0.830, sensitivity 72.1%, specificity 72.7%).

Table 1 Factors independently related to performing chest X-rays

| Groups | P | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Group 1 | ||||

| Cough | <0.001 | 32.158 | 9.330 | 110.845 |

| Dyspnea | <0.001 | 20.360 | 9.242 | 44.852 |

| Fever | <0.001 | 10.878 | 4.253 | 27.824 |

| GI bleeding | 0.010 | 0.143 | 0.033 | 0.624 |

| Chest pain | <0.001 | 3.776 | 2.438 | 5.849 |

| Rales | <0.001 | 3.128 | 1.655 | 5.911 |

| Oedema | 0.047 | 2.166 | 1.011 | 4.640 |

| Age | 0.001 | 1.018 | 1.007 | 1.029 |

| Group 2 | ||||

| Cough | <0.001 | 17.498 | 5.849 | 52.350 |

| Dyspnea | <0.001 | 14.862 | 6.932 | 31.863 |

| Arrhythmia | 0.001 | 0.107 | 0.029 | 0.393 |

| Rales | <0.001 | 7.107 | 2.780 | 18.167 |

| Fever | <0.001 | 4.861 | 2.233 | 10.581 |

| Chest pain | <0.001 | 4.172 | 2.727 | 6.381 |

| GCS | 0.003 | 0.793 | 0.679 | 0.925 |

| Age | <0.001 | 1.020 | 1.011 | 1.030 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; GI: gastrointestinal; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale.

Table 2 Factors independently related to pathologic chest X-ray findings

| Groups | P | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Group 1 | ||||

| Age | <0.001 | 1.047 | 1.027 | 1.066 |

| Dyspnea | <0.001 | 4.160 | 2.057 | 8.413 |

| Cough | 0.021 | 2.929 | 1.175 | 7.303 |

| Rales | <0.001 | 5.535 | 2.839 | 10.792 |

| Workday | 0.037 | 0.526 | 0.288 | 0.961 |

| Heart failure | 0.045 | 2.475 | 1.021 | 6.000 |

| GCS | <0.001 | 0.758 | 0.692 | 0.830 |

| Group 2 | ||||

| Age | <0.001 | 1.031 | 1.018 | 1.045 |

| Dyspnea | 0.001 | 2.582 | 1.451 | 4.594 |

| Cough | 0.015 | 2.522 | 1.195 | 5.325 |

| Rales | 0.098 | 1.742 | 0.903 | 3.360 |

| Male sex | 0.056 | 0.640 | 0.405 | 1.011 |

| Heart failure | 0.005 | 3.031 | 1.386 | 6.628 |

| GCS | <0.001 | 0.853 | 0.801 | 0.908 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale.

Similar number of patients died within ED during workup (0.9% vs. 1.4%, P=0.452). Among the discharged patients, five (0.2% vs. 0.3%, P=1.000) died within 30 days of ED discharge. Intra-hospital and 30-day mortality for admitted patients were comparable (9.8% vs. 11.8%, P=0.498; 10.2% vs. 12.3%, P=0.501). Rates of CXR examinations did not differ between the two groups when analyzed against outcome (survivors 38.6% vs. 42.0%, P=0.149; non-survivors 58.3% vs. 70.0%, P=0.675).

DISCUSSION

In this single-center retrospective observational study, shifting from IMSs to EPSs within the internal medicine ED section did not affect the CXR rate. This disputes our hypothesis, which was based on the acknowledged differences in the levels of experience and education between EPSs and IMSs in the field of internal medicine. No difference was observed in patients with common high-risk factors such as hypotension, dyspnea, chest pain, or lower Glasgow Coma Scale. The possible explanation for this uniformity of workup for severe patients is that the algorithms for such patients mastered during training are similar, and consequently the workup is comparable as well, despite the absence of written recommendations. On the other hand, patients in whom the clinical presentation may be obscured, such as older patients, especially older females (but not female patients in general), and patients with a history of malignancy, were more radiographed in G2. Moreover, more CXR examinations were performed in G2 during off-hours and night shifts compared with G1. This could be related to a lack of expertise and diagnostic uncertainty during the time when additional consultations are not easily available. Other studies reported similar reasons for inappropriate radiologic workup: medico-legal issues,[5] diagnostic uncertainty,[6] inadequate education and training,[7] requests from consulting subspecialty physicians, increased workloads within the ED,[8] and patient self-referral.[9] Contrary to our data, Gardiner and Zhai[10] reported just 0.8% of CXRs performed during off hours as inappropriate in a study from a teaching hospital in Australia.

The sensitivity to routine CXR could explain the difference recorded for the patients presenting with GI bleeding. Occasionally, gastroenterologists performing urgent endoscopies insist on radiographic investigations, although there is no specific local protocol involving CXR. This may be a possible explanation of the higher CXR rates in patients presenting with GI bleeding. Contrary to IMSs, who have various obligations within their (sub)specialties, EPSs spend their working time exclusively within the ED. This provides them with the possibility to tailor strategies required for particular pathologies. Occasionally, this leads to a generalized approach and unnecessary workup, particularly in instances when the final treatment is performed by other specialists. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggests that CXR should be considered only in patients with new respiratory signs or symptoms of decompensated heart failure, and routine chest radiography is not recommended before endoscopy.[11] In a meta-analysis of 14,390 preoperative CXRs, unexpected findings were observed in 1.3% of the cases, while only 0.1% of the findings affected the way the patient was treated.[12] Benacerraf et al[13] concluded that in patients under 40 years old with no symptoms CXR should be omitted. Such a guideline could reduce the number of CXRs in this population by 58%. In this study, 24.7% of patients under 40 years underwent CXR. Although the absolute and relative numbers of such patients were low, they could be reduced even further should written protocols be provided.

We observed a non-significant tendency to resolve arrhythmias more promptly in G2 (221 [180-485] minutes vs. 209 [142-372] minutes, P=0.159). This was possibly due to self-governing procedural sedation for electric cardioversion in G2 (acquired during EPS training), as opposed to sedation managed by anesthesiologists in G1. For the same reason (independent treatment, as opposed to examinations performed by other physicians), the workup was less generalized, leading to a higher number of patients in whom CXR could be omitted in G2. Although academic societies provide no clear guideline on CXR in patients presenting with arrhythmia, performing CXR on patients presenting with signs and symptoms of congestion is plausible. Stiell et al[14] presented data on 1,091 patients treated for atrial flutter of fibrillation within the EDs in six Canadian academic hospitals. CXR was performed on all patients. The authors found that radiographic findings of pulmonary congestion, detected in 2.2% of the patients, independently predicted the occurrence of adverse events within 30 days from enrollment.

The majority of EPSs utilize bedside ultrasound, including protocoled examinations such as focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST).[15] Such examinations were previously shown to reduce the number of other radiologic examinations, mainly computed tomography.[16] Although this issue was not directly assessed in our study, and the propensity score matching was composed to standardize the tendency to perform CXR, the G2 patients underwent significantly fewer comprehensive abdominal ultrasounds and computed tomographies. This could be appreciated as an advancement of professional ED staffing, and further disputes our hypothesis.

We found IMSs to be more detailed in reporting the radiologic findings in discharge letters. While the significance of this result is hard to assess (possibly being a mere difference in referral style), it is in accordance with the differences in training. While IMSs pay more attention to pathophysiological pathways and tend to explain the diagnostic and treatment decisions more thoroughly, EPSs employ a more “surgical” approach: focused, resolute, and characterized by concise reporting. The same can be stated for differences in the reporting of physical findings. Although there was no objective way to rate the number of missed auscultation findings, the results suggest that some lung phenomena may have been missed, or at least underreported in G2. Moreover, in regression analysis, the auscultation finding was the most independent predictor of pathological CXR in G1. Whether this has an impact on the quality of emergency care is not clear.

Similar variables were associated with obtaining CXR in logistic regression in both groups. Although there are no written recommendations, routine CXR for all patients is strongly discouraged. We were unable to find equivalent data regarding non-trauma ED visits for a prediction model comparison in the literature. The rate of CXRs performed in the ED is similar to the ones in other studies. In the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, X-ray imaging was performed in 33.7% out of 49,061 ED visits.[17] In patients assessed for acute cardiac ischemia, Katz et al[18] reported an 85.8% CXR referral rate for EPSs classified as the highest tertile of the malpractice fear score, compared with 73.5% in the lowest tertile. The corresponding percentage for chest pain patients in our study was 56.3%.

In the prediction models for pathological findings, five out of seven variables were identical, with the same order when ranked according to level of significance. All variables were easily obtainable by history taking and physical examination. By ROC curve analysis, a significantly better prediction of pathological findings was achieved for G1. A study reported similar rates of pathological findings,[19] although there were series with considerably lower rates.[20] Al Zadjali et al[20] reported higher rates of normal findings in young, non-dyspneic, and non-tachypneic patients, as well as in patients with no significant medical history. In patients presenting with chest pain, Hess et al[21] reported an absence of a history of congestive heart failure or smoking, and no abnormalities on lung auscultation as factors required to forgo CXR.

Whether the observed difference in antibiotic prescription rates was the result of a systematically different approach should be assessed in further studies. Huang et al[22] indicated that IMSs and EPSs employed a similar approach to patients with pneumonia. Conversely, Wigton et al[23] reported restrictive antibiotic prescription habits for urinary tract infection in EPSs compared with IMSs.

Study limitations

This was a retrospective observational study. Although a propensity score matching was performed, the results obtained from this study population cannot be unequivocally applied to the general population. The study was conducted during the winter period, possibly leading to a higher percentage of CXRs due to the seasonal peak in respiratory infections. The authors wanted to share their explanation of the significant differences obtained in the analysis, although the majority of them remained within the sphere of speculation.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, moving to EPS staffing in the ED does not lead to an increase in radiologic workup. By implementing deliberate usage of ultrasound, some self-governing procedures, case-oriented investigations, and center-specific recommendations, unnecessary radiologic workup can be avoided. Professional ED staffing could lead to a higher standard of emergency care.

Funding: This study did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the Sestre Milosrdnice University Hospital Center Ethics Committee (251-29-11-20-01-8).

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors: MP was involved in study concept and design, statistical analysis, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. LK conducted data acquisition, and provided statistical expertise and critical revision. IK was involved in study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, language editing, and critical revision. KŽ carried out data acquisition, language editing, and critical revision of the manuscript. VD was involved in study concept and design, study approval and collection of the data, critical analysis of statistical methods, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Reference

Development of emergency medicine in Europe

DOI:10.1111/acem.12126

URL

PMID:23672367

[Cited within: 1]

Emergency medicine (EM) is emerging worldwide. Its development as a recognized specialty is proceeding at difference rates in different countries. Europe is a region with complex political affiliations and is composed of countries both within and outside the European Union (EU). Europe is seeking greater standardization (harmonization) for mutually improved economic development. Medicine in general, and EM in particular, is no exception. In Europe, as in other regions, EM is struggling for acceptance as a valid field of specialization. The European Union of Medical Specialists requires that once two-fifths of countries acknowledge a specialty, all EU countries must address the question. EM had achieved the needed majority by 2011. This article briefly describes the European road to specialty acceptance.

Emergency medicine as a specialty in the European context

Optimizing diagnostic imaging in the emergency department

DOI:10.1111/acem.12640

URL

PMID:25731864

[Cited within: 1]

While emergency diagnostic imaging use has increased significantly, there is a lack of evidence for corresponding improvements in patient outcomes. Optimizing emergency department (ED) diagnostic imaging has the potential to improve the quality, safety, and outcomes of ED patients, but to date, there have not been any coordinated efforts to further our evidence-based knowledge in this area. The objective of this article is to discuss six aspects of diagnostic imaging to provide background information on the underlying framework for the 2015 Academic Emergency Medicine consensus conference,

Chest radiography in the emergency department

DOI:10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80558-3

URL

PMID:3511787

[Cited within: 1]

A review of the medical literature was carried out to determine guidelines for cost-effective and safe use of chest radiography in the emergency department. Screening radiographs are indicated in specific populations in the search for occult tuberculosis or carcinoma and in routine or preoperative cases. Radiography is clinically indicated in the asthmatic patient, the elderly patient, and the symptomatic patient, and its indications are modified by the patient's age and presenting signs and symptoms. Based on the information reviewed, rational guidelines for the use of chest radiography are presented.

Head multidetector computed tomography: emergency medicine physicians overestimate the pretest probability and legal risk of significant findings. Am

[J]

Invited commentary—Emergency department neuroimaging: are we using our heads?: Comment on “Use of neuroimaging in US emergency departments”

DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.520 URL PMID:21325119 [Cited within: 1]

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Evidence-based Medicine Interest Group. A survey to determine the prevalence and characteristics of training in evidence-based medicine in emergency medicine residency programs.

[J]

Emergency physician perceptions of medically unnecessary advanced diagnostic imaging

DOI:10.1111/acem.12625

URL

PMID:25807868

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVES: The objective was to determine emergency physician (EP) perceptions regarding 1) the extent to which they order medically unnecessary advanced diagnostic imaging, 2) factors that contribute to this behavior, and 3) proposed solutions for curbing this practice. METHODS: As part of a larger study to engage physicians in the delivery of high-value health care, two multispecialty focus groups were conducted to explore the topic of decision-making around resource utilization, after which qualitative analysis was used to generate survey questions. The survey was extensively pilot-tested and refined for emergency medicine (EM) to focus on advanced diagnostic imaging (i.e., computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). The survey was then administered to a national, purposive sample of EPs and EM trainees. Simple descriptive statistics to summarize physician responses are presented. RESULTS: In this study, 478 EPs were approached, of whom 435 (91%) completed the survey; 68% of respondents were board-certified, and roughly half worked in academic emergency departments (EDs). Over 85% of respondents believe too many diagnostic tests are ordered in their own EDs, and 97% said at least some (mean = 22%) of the advanced imaging studies they personally order are medically unnecessary. The main perceived contributors were fear of missing a low-probability diagnosis and fear of litigation. Solutions most commonly felt to be

Addressing overutilization in medical imaging

DOI:10.1148/radiol.10100063

URL

PMID:20736333

[Cited within: 1]

The growth in medical imaging over the past 2 decades has yielded unarguable benefits to patients in terms of longer lives of higher quality. This growth reflects new technologies and applications, including high-tech services such as multisection computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and positron emission tomography (PET). Some part of the growth, however, can be attributed to the overutilization of imaging services. This report examines the causes of the overutilization of imaging and identifies ways of addressing the causes so that overutilization can be reduced. In August 2009, the American Board of Radiology Foundation hosted a 2-day summit to discuss the causes and effects of the overutilization of imaging. More than 60 organizations were represented at the meeting, including health care accreditation and certification entities, foundations, government agencies, hospital and health systems, insurers, medical societies, health care quality consortia, and standards and regulatory agencies. Key forces influencing overutilization were identified. These include the payment mechanisms and financial incentives in the U.S. health care system; the practice behavior of referring physicians; self-referral, including referral for additional radiologic examinations; defensive medicine; missed educational opportunities when inappropriate procedures are requested; patient expectations; and duplicate imaging studies. Summit participants suggested several areas for improvement to reduce overutilization, including a national collaborative effort to develop evidence-based appropriateness criteria for imaging; greater use of practice guidelines in requesting and conducting imaging studies; decision support at point of care; education of referring physicians, patients, and the public; accreditation of imaging facilities; management of self-referral and defensive medicine; and payment reform.

Are all after-hours diagnostic imaging appropriate? An Australian emergency department pilot study

Routine laboratory testing before endoscopic procedures

DOI:10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.019

URL

[Cited within: 1]

This is a clinical update discussing the use of periendoscopic laboratory testing in common clinical situations. The Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) prepared this document by using MEDLINE and PubMed databases to search for publications between January 1990 and December 2013 pertaining to this topic. The keywords "endoscopy" and "laboratory" were used with each of the following: "preanesthesia," "preoperative," "routine," "screening," and "testing." The search was supplemented by accessing the "related articles" feature of PubMed with articles identified on MEDLINE and PubMed as the references. Additional references were obtained from the bibliographies of the identified articles and from recommendations of expert consultants. When few or no data were available from well-designed prospective trials, emphasis was given to results from large series and reports from recognized experts. Weaker recommendations are indicated by phrases such as "We suggest...," whereas stronger recommendations are stated as "We recommend..." The strength of individual recommendations was based on both the aggregate evidence quality (Table 1)(1) and an assessment of the anticipated benefits and harms.

ASGE guidelines for appropriate use of endoscopy are based on a critical review of the available data and expert consensus at the time that the documents are drafted. Further controlled clinical studies may be needed to clarify aspects of this document. This document may be revised as necessary to account for changes in technology, new data, or other aspects of clinical practice and is solely intended to be an educational device to provide information that may assist endoscopists in providing care to patients. This document is not a rule and should not be construed as establishing a legal standard of care or as encouraging, advocating, requiring, or discouraging any particular treatment. Clinical decisions in any particular case involve a complex analysis of the patient's condition and available courses of action. Therefore, clinical considerations may lead an endoscopist to take a course of action that varies from the recommendations and suggestions proposed in this document.

Value of routine preoperative chest X-rays: a meta-analysis.

[J]

An assessment of the contribution of chest radiography in outpatients with acute chest complaints: a prospective study

DOI:10.1148/radiology.138.2.7455106

URL

PMID:7455106

[Cited within: 1]

The contribution of chest radiography to diagnosis was assessed in 1,102 consecutive patients with chest complaints at the Emergency Ward and Ambulatory Screening Clinic of a large hospital. The goal of this prospective study was to identify selective indications for chest radiography in this population with relation to the patient's age, the symptoms, and the results of physical examination. Although in patients over 40 years old chest symptoms are a sufficient indication for chest radiography, 96% of the patients below age 40 had a normal physical examination of the chest, no hemoptysis, and no acute radiographic abnormalities. If chest radiographs in the below-40 group had been limited to patients to patients with abnormal physical examinations and/or hemoptysis, 58% of the patients in that group would have been spared the examination. Under these conditions, 2.3% of the acute radiographic abnormalities in the entire population of patients under 40 would have gone undetected.

Outcomes for emergency department patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter treated in Canadian hospitals

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.013

URL

PMID:28110987

[Cited within: 1]

STUDY OBJECTIVE: Recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter are the most common arrhythmias managed in the emergency department (ED). We evaluate the management and 30-day outcomes for recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter patients in Canadian EDs, where cardioversion is commonly practiced. METHODS: We conducted a prospective cohort study in 6 academic hospital EDs and enrolled patients who had atrial fibrillation and flutter onset within 48 hours. Patients were followed for 30 days by health records review and telephone. Adverse events included death, stroke, acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, subsequent admission, or ED electrocardioversion. RESULTS: We enrolled 1,091 patients with mean age 63.9 years, atrial fibrillation 84.7%, atrial flutter 15.3%, hospital admission 9.0%, and converted to sinus rhythm 80.1%. Although 10.5% of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter patients had adverse events within 30 days, there were no related deaths and 1 stroke (0.1%). Adjusted odds ratios for factors associated with adverse event were hours from onset (1.03/hour; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01 to 1.05), history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (2.09; 95% CI 1.01 to 4.36), and pulmonary congestion on chest radiograph (7.37; 95% CI 2.40 to 22.64). Patients who left the ED in sinus rhythm were much less likely to experience an adverse event (P<.001). CONCLUSION: Although most recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter patients were treated aggressively in the ED, there were few 30-day serious outcomes. Physicians underprescribed oral anticoagulants. Potential risk factors for adverse events include longer duration from arrhythmia onset, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, pulmonary congestion on chest radiograph, and not being in sinus rhythm at discharge. An ED strategy of sinus rhythm restoration and discharge in most patients is effective and safe.

Prospective evidence of the superiority of a sonography-based algorithm in the assessment of blunt abdominal injury.

[J]

Retrospective analysis of eFAST ultrasounds performed on trauma activations at an academic level-1 trauma center. World

[J]

National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2016 emergency department summary tables

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2016_ed_web_tables.pdf Available at .

Emergency physicians’ fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.04.016

URL

[Cited within: 1]

Study objective

We evaluate the association between emergency physicians' fear of malpractice and the triage and evaluation patterns of patients with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

We surveyed 33 emergency physicians of 2 university hospitals during the preintervention phase of an implementation trial of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Unstable Angina guideline in 1,134 study patients. The survey included a 6-item instrument that addressed concerns about malpractice and a measure of general risk aversion. We used hierarchical logistic regression to model emergency department (ED) triage decisions and diagnostic testing as a function of fear of malpractice, with adjustment for patient characteristics, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guideline risk group, study site, and clustering by emergency physician.

Results

Overall, emergency physicians in the upper tertile of malpractice fear were less likely to discharge low-risk patients compared with emergency physicians in the lower tertile (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.12 to 0.99; P=.05). Patients treated by emergency physicians in this group were also more likely to be admitted to an ICU or telemetry bed (adjusted OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.4). In addition, emergency physicians in the upper tertile of malpractice fear were more likely to order chest radiography, as well as cardiac troponin. Malpractice fear accounted for a similar amount of variance after controlling for emergency physicians' risk aversion.

Conclusion

Malpractice fear accounts for significant variability in ED decisionmaking and is associated with increased hospitalization of low-risk patients and increased use of diagnostic tests.

X-ray use in chest imaging in emergency department on the basis of cost and effectiveness

DOI:10.1016/j.acra.2016.05.008

URL

PMID:27426978

[Cited within: 1]

RATIONALE AND OBJECTIVES: The increasing use of imaging in the emergency department (ED) services has become an important problem on the basis of cost and unnecessary exposure to radiation. Radiographic examination of the chest has been reported to be performed in 34.4% of ED visits, and chest computerized tomography (CCT) in 15.8%, whereas some patients receive both chest radiography and CCT in the same visit. In the current study, it was aimed to establish instances of medical waste and unnecessary radiation exposure and to show how the inclusion of radiologists in the ordering process would affect the amount of unnecessary imaging studies. MATERIALS AND METHODS: This retrospective study included 1012 ED patients who had both chest radiography and CCT during the same visit at Ankara Training and Research Hospital between April 2015 and January 2016. The patients were divided into subgroups of trauma and nontrauma. To detect unnecessary imaging examinations, data were analyzed according to the presence of additional findings on CCT images and the recommendation of a radiologist for CCT imaging. RESULTS: In the trauma group, 77.1% (461/598) and in the nontrauma group, 80.4% (334/414) of patients could be treated without any need for CCT. In the trauma group, the radiologist recommendation only, and in the nontrauma group, both the radiologist recommendation and the age were determined to be able to predict the risk of having additional findings on CCT. CONCLUSIONS: Considering only the age of the patient before ordering CCT could decrease the rate of unnecessary imaging. Including radiologists into both the evaluation and the ordering processes may help to save resources and decrease exposure to ionizing radiation.

Predictors of positive chest radiography in non-traumatic chest pain in the emergency department

DOI:10.5001/omj.2009.6

URL

PMID:22303504

[Cited within: 2]

OBJECTIVES: To determine predictors associated with positive chest x-ray finding in patients presenting with non-traumatic chest pain in the Emergency Department (ED). METHODS: Health records, including the final radiology reports of all patients who presented with non-traumatic chest pain and had a chest x-ray performed in an urban Canadian tertiary care ED over four consecutive months were reviewed. Demographic and clinical variables were also extracted. Chest x-ray findings were categorized as normal (either normal or no significant change from previous x-rays) or abnormal. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine the association between various predictors and chest x-ray finding (positive/negative). RESULTS: The 330 study patients had the following characteristics: mean age 58+/-20 years; female 41% (n=134). Patients' chief complaints were only chest pain 75% (n=248), chest pain with shortness of breath 12% (n=41), chest pain with palpitation 4% (n=14), chest pain with other complaints 9% (n=28). Chest x-rays were reported as normal or no acute changes in 81% (n=266) of patients, and abnormal in 19% (n=64) of patients. The most common abnormal chest x-ray diagnoses were congestive heart failure (n=28; 8%) and pneumonia (n=17; 5%). Those with abnormal chest x-ray findings were significantly older (71 versus 55 years; p<0.001), had chest pain with shortness of breath (36% versus 11%; p<0.001), had significant past medical history (39% versus 14%; p<0.001), and were also tachypnoic (31% versus 12%; p<0.001). CONCLUSION: This study found that patients with non-traumatic chest pain are likely to have a normal chest x-ray if they were young, not tachypnoeic or short of breath, and had no significant past medical history. A larger study is required to confirm these findings.

Derivation of a clinical decision rule for chest radiography in emergency department patients with chest pain and possible acute coronary syndrome

DOI:10.1017/s148180350001215x

URL

PMID:20219160

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: We derived a clinical decision rule to determine which emergency department (ED) patients with chest pain and possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS) require chest radiography. METHODS: We prospectively enrolled patients over 24 years of age with a primary complaint of chest pain and possible ACS over a 6 month period. Emergency physicians completed standardized clinical assessments and ordered chest radiographs as appropriate. Two blinded investigators independently classified chest radiographs as

Comparison of emergency physicians and internists regarding core measures of care for admitted emergency department boarders with pneumonia.

[J]

Variation by specialty in the treatment of urinary tract infection in women.

[J]DOI:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.05398.x URL [Cited within: 1]