INTRODUCTION

Emergency medical service system (EMSS), including pre-hospital emergency care and hospital-based emergency departments (EDs), is essential in providing acute care services for a range of health conditions, such as life-threatening injuries, acute cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and complications due to pregnancy.

The quality and responsiveness of EMSS reflect the level of health care in a country. Following China’s national meeting on health and the announcement of the “Healthy China 2030” plan, marked changes have been initiated to expand or advance the Chinese healthcare system, including broadening enrollment in the universal medical insurance system, health profession workforce development, and hierarchical medical treatment system. In particular, larger tertiary hospitals, which are responsible for acute and critical patients according to these reform policies, will face an influx of emergency and critically ill patients as the healthcare regionalization in China continues. In 2017, China’s EDs of hospitals managed an estimated 166.5 million visits, and the requirement for high-quality acute and critical care services will grow exponentially through improved and more regionalized healthcare delivery.[1]

However, trends of emergency and acute care in China have not been studied systematically to date. In this study, we quantified and described the trends of emergency visits, capabilities, and challenges of China’s EMSS in the past decade in detail. Our findings can offer a theoretical basis for improving the quality of emergency care in China, and help the world to understand China’s EMSS. Additionally, our reports are able to provide experience to the EMSS development worldwide, especially for the developing countries with similar conditions.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched for publications and other materials describing or evaluating EMSS of China both in Chinese and English. We reviewed the official documents issued by the Ministry of Health (MOH, now the National Health and Family Planning Commission), yearbooks, published reports, and news reports from domestic and international sources. We also searched PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang databases, and Baidu data, and manually screened the references of relevant articles. Our search strategy included the terms “emergency medical service”, “emergency medicine”, “emergency care”, “acute care”, “emergency department”, “emergency room”, “pre-hospital emergency care”, and “ambulance”, combined with the terms “China” and “Chinese”, or combined with the terms “overcrowding”, “crowding”, “length of stay”, “boarding time”, “access block”, “medical disputes”, “medical complaints”, “medical disturbance”, “medical violence”, “doctor-patient relationship”, “environment”, “condition”, “situation”, “workforce”, “human resources”, “exhaustion”, “burnout”, “overload”, “staff retention”, “staff recruitment”, “staff enrollment”, “staff shortage”, and “staff stability”. We also searched the websites of Chinese Government agencies for related documents and statistics.

Data collection of emergency visit numbers in China

The China Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbooks (2006-2018) described and analyzed the medical and health services, the health status of residents, and family planning in the Chinese mainland in the previous years, which were the key references of our study.[1,2] All hospitals in China were assessed, excluding maternal and child health hospitals, specialized prevention stations, and sanatoriums. The raw data on the number of emergency visits, including patients presenting to EDs of hospitals and pre-hospital emergency care, were extracted from the China Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbooks 2008-2018 and 2010-2018,[1,2] respectively. In the yearbook 2008, the number of patients presenting to EDs of hospitals in 2007 was first recorded, while the number of patients presenting to pre-hospital emergency care was first included in the yearbook 2010. Thus, the related data were extracted and analyzed from the corresponding years.

Data collection of capabilities of emergency and acute care in China

Capabilities of EMSS were evaluated by the number of licensed emergency physicians, beds in hospital-based EDs, and the health workforce in pre-hospital emergency care. The health workforce in pre-hospital emergency care covers licensed doctors, assistant doctors, and nurses. The original data were also derived from the China Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbooks 2006-2018.[1,2] The number of emergency physicians in EDs in 2005 was first recorded in the yearbook 2006, but the data in 2006-2008 were not counted in the yearbooks 2007-2009. The number of beds in EDs in 2007 was recorded in the yearbook 2008 for the first time. Thus, the related data were extracted and analyzed from the corresponding years.

RESULTS

Growing number of emergency visits during the past decade

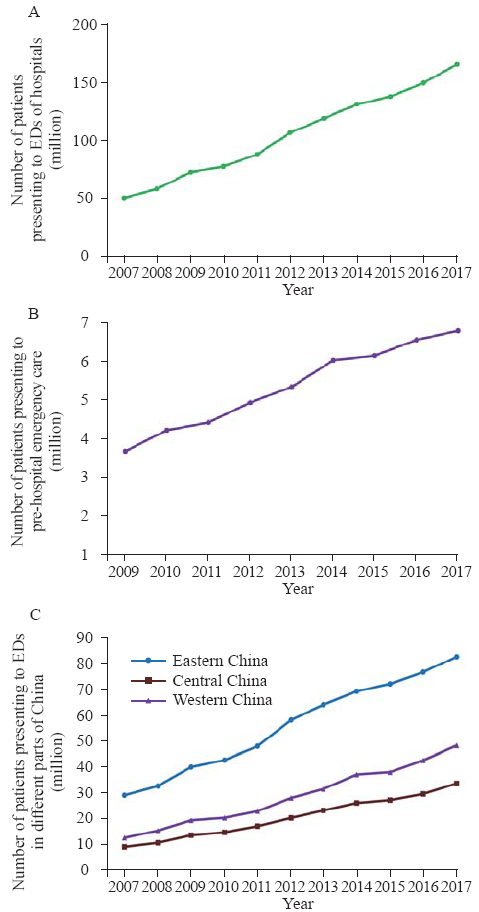

During the past decade, the number of patients presenting to EDs has increased among all levels of hospitals in China. From 2007 to 2017, the number of ED visits tripled, from 51.9 million to 166.5 million (Figure 1A). The Chinese population reliant on the ED for clinical care was also increased as reflected by the rise from 3.28% in 2007 to 4.95% in 2017 in the proportion of ED visits relative to all clinical visits. Commensurate with rising demand for ED care, the utilization of pre-hospital emergency care increased by 113% from 3.2 million to 6.8 million between 2009 and 2017 (Figure 1B). In addition, from 2007 to 2015, the number of patients presenting to EDs of hospitals in the eastern, central, and western regions of China increased by 183%, 262%, and 277%, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Statistical graphs of changes in numbers of patients presenting to hospitals’ EDs and to pre-hospital emergency care in China. A: from 2007 to 2017, the number of ED visits tripled; the data before 2007 were not counted in China’s yearbooks; B: from 2009 to 2017, the utilization of pre-hospital emergency care increased by 113%; the data before 2009 were not counted in China’s yearbooks; C: from 2007 to 2017, the number of patients presenting to EDs of hospitals in the eastern, central, and western regions of China increased by 183%, 262% and 277%, respectively; EDs: emergency departments.

Enhanced capabilities of EMSS during the past decade

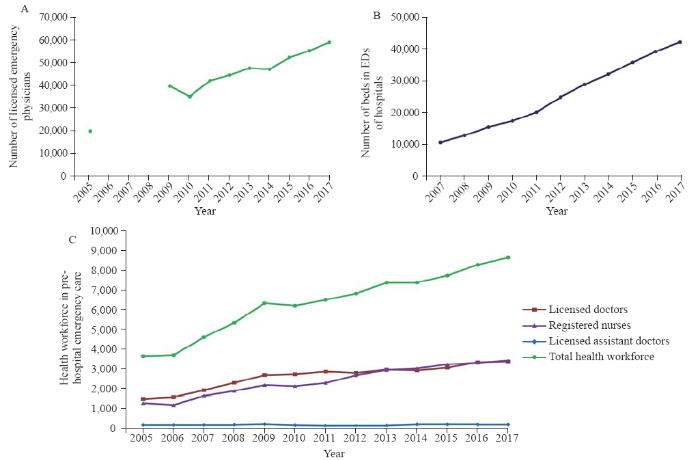

Between 2005 and 2017, the number of licensed emergency physicians in EDs of hospitals increased by 196% from 20,058 to 59,409 (Figure 2A) with the data in 2006-2008 missing, and the proportion of emergency physicians among all doctors increased by 40% from 1.5% in 2005 to 2.1% in 2017. The total number of beds in hospital-based EDs in China increased from 10,783 in 2007 to 42,367 in 2017 (Figure 2B). Likewise, in the pre-hospital settings, the size of the health workforce doubled from 3,687 to 8,671, with a 109% increase in the number of physicians from 1,774 to 3,712 and 165% of registered nurses from 1,314 to 3,478 between 2005 and 2017 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Statistical graphs of changes in workforce and number of beds in EMSS in China. A: over the past decade, the number of licensed emergency physicians at hospitals in China increased by 196%; the data of 2006, 2007, and 2008 were not counted in China’s yearbooks; B: the number of beds in EDs increased from 10,783 in 2007 to 42,367 in 2017; the data before 2007 were not counted in China’s yearbooks; C: for pre-hospital emergency care, the volume of health workforce doubled, including a 109% increase in the number of physicians. EMSS: emergency medical service system; EDs: emergency departments.

Challenges faced by China’s EMSS

Despite improvements in infrastructure and expansion of resources dedicated to acute and critical care in China’s EMSS, several substantial challenges persisted, which made contributions to the phenomenon that the overall mortality of emergency patients increased in tertiary hospitals although decreased all over China during the past decade.[3]

Overcrowding and the long length of stay in EDs

A recent survey of 33 tertiary hospitals in 31 provinces conducted by the Chinese College of Emergency Physicians documented that overcrowding in EDs was very common, as reflected by frequent ambulance diversion, a rare event prior to recent reforms.[4] In a cross-sectional survey of 43 tertiary and secondary hospitals in Beijing, 30.2% reported overcrowding, and 34.9% had instances of more than five emergency patients experiencing admission delays over 72 hours.[5]

The length of stay in EDs in China is considerable, with 50% of Beijing EDs reporting longer than 6 hours on average, which stands in contrast to a national average length of stay of 154 minutes in the USA with only 11.1% of patients spending over 6 hours in the ED.[6,7] A study of 17 tertiary hospitals from 12 provinces documented that in 77% of EDs over 50% of patients suffered access block to inpatient wards in 2012 (compared to 34% of EDs in 2000, and 25% in the 1980s).[8] Moreover, in an analysis from a typical hospital in Shanghai, 2,702 patients during one year waited in the EDs for over 48 hours.[9]

Poor work environment

The poor work environment of China’s hospitals has been well documented;[10] however, the degree to which patient distrust complicates EMSS care is even more extreme.[4,8,11] Particularly notable to EMSS are frequent medical disputes, complaints, and even violence.[12] The latter disturbances have a substantial influence on EMSS doctors who try to make more rapid and efficient decisions while also engage patients and families at the time of acute illness. A notable example of distrust with real implications for patient outcomes is that of EMSS patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). These patients face the prolonged door to balloon (D to B) time and are less likely to meet the optimal treatment window for coronary revascularization and myocardial reperfusion.[13,14] As a reflection of this adversarial work environment, the proportion of EDs facing five or more medical disputes increased from zero in 1980 to nearly 12% in 2012. Furthermore, the rate of medical complaints increased dramatically from 11.1% to 70.6% within the same timeframe.[8] Such an adversarial atmosphere is also not limited to words or written complaints; a commensurate rise in physical violence towards healthcare providers has been seen with survey data indicating that two-thirds of violence towards healthcare providers occurs in the ED.[11] With such a toxic work environment, emergency healthcare providers, including physicians, nurses, and ancillary staff, face increasing exhaustion and burnout, which further threatens the quality and safety of acute care.

Work exhaustion of emergency workforce

Compared to the USA, China has a higher ratio of emergency physicians per patient capita, with 3.4 in China and 2.9 in the USA in 2015, per 10,000 emergency patients.[15,16] However, exhaustion and burnout remain serious concerns for the Chinese EMSS workforce in the larger hospitals of most regions, who manage an increasingly large population with longer admission time, overcrowding, and medical violence. Workplace exhaustion in China is common with 85% of Chinese physicians reporting medium to high emotional exhaustion scores, and 88% reporting medium to high depersonalization scores.[17] The situation is more severe than that in developed countries, for example, 59% and 66% respectively in the United Kingdom, 46% and 93% in Canada, and 65% with medium to high burnout scores in the USA. Notably, emergency physicians in China reported higher proportions of both scores compared with other physicians.[17,18] As a result of the poor work conditions and lifestyle that result from workforce shortages, many EDs face increasing challenges in staff retention and recruitment. Even among top-ranking EDs in China, nearly 50% of newly recruited physicians commonly come from other departments, and only 10%-20% of undergraduates compared to other disciplines register annually for the graduate admission exam of emergency medicine. Reports in China demonstrated that the low staff retention rate in EDs was a persistent problem.[4,12] Workforce shortages are the most severe in pre-hospital emergency care, with annual staff turnover approaching 50% in large cities such as Beijing, Xi’an, and Shanghai.[11,19-21] Mental exhaustion and consequent staff instability and shortage affect the Chinese medical system overall. The situation is acute in the fields of the EMSS, similar to pediatrics.[22]

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described and quantified the trends and challenges of EMSS from 2005 to 2017 in China, and found that the number of emergency visits was growing with continually enhancing capabilities during the past decade. However, overcrowding, the long length of stay in EDs, poor work environment, and the work exhaustion of emergency physicians and nurses are still the critical challenges faced by China’s EMSS.

The policies on China’s EMSS were initially developed by the Ministry of Health in the 1980s.[23] China’s EMSS grew very slowly during the first twenty years, but has advanced relatively quickly for the past decade. Because of the accelerating pace of life, unhealthy lifestyles and diets, environmental pollution, the aging process, and more frequent traffic accidents, the annual incidence of virtually all major acute and critical illnesses has been rising in China.[24] In addition, with the expansion of public medical insurance systems, more and more rural residents and rural migrants have gained access to health insurance similar with that of urban residents. As a result, the ED visit rates have been rising among all levels of hospitals in China, from 51.9 million in 2007 to 166.5 million in 2017. As in the USA, the number of ED visits grew faster than the population from 90.8 million in 1992 to 133.2 million in 2012 with a number of reasons, such as the immediate access to diagnostic resources that EDs provide.[25]

To meet the rapid increasing demand and the public health emergencies, a large number of medical resources have been assigned for improving the quality and efficiency of EMSS in China.[26,27] After experiencing the pandemic threats of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003, the Chinese government expanded emergency rescue and preparedness via staffing and physical improvements to medical facilities. Thanks to the improved medical resources, the annual mortality of emergency patients decreased from 0.12% in 2005 to 0.08% in 2015.[3]

Despite the expansion of resources and improvements in infrastructure in acute and critical care in China’s EMSS, some substantial challenges still remain, including overcrowding and the long length of stay in EDs, poor work environment, work exhaustion, and consequent instability of emergency workforce. These issues are still critical challenges faced by China’s EMSS, and they could be contributing to the phenomenon that the mortality of EDs was steady and even slightly increased in tertiary hospitals although decreased all over China during the past decade.[3] Not only China, but also the whole developing world and even some developed countries are facing these critical challenges.[18, 28-30]

As is the case among many developing and developed countries, overcrowding and significantly increasing throughput in China’s EDs have become widespread, particularly at regional central hospitals.[31] The average length of stay in EDs around China, such as EDs in Beijing, seems similar with that of 15 medical centers from 59 low- and middle-income countries with the median time as long as 7.7 hours.[32] However, this is not satisfactory compared with developed countries, such as the USA. EDs’ overcrowding and the long length of stay are associated with worse quality and safety of emergency care, as well as patients’ morbidity and mortality.[33,34]

Beyond rising patient volumes, the overcrowding and long length of stay in EDs should be also partially attributed to that a large number of Chinese patients are more likely to skip primary care and go directly to tertiary hospitals, and that more people have easier access to EDs especially in tertiary hospitals. In China, people face imbalances in high-quality medical resources, variations in behavioral idiosyncrasies, insufficient inpatient bed capacity, insufficient staff, and limitations driven by medical insurance policies, which are also faced by other developing countries.[35] Secondary to a significant imbalance in medical quality at different hospitals, a weak health referral system, and traditional behavioral patterns, Chinese patients are more likely to avert primary care and go directly to tertiary hospitals, resulting in bed overuse at regional central hospitals and bed underuse at primary care hospitals. At regional central hospitals, the number of beds and the volume of medical personnel are limited. Furthermore, medical insurance systems impose restrictions on medical care, influencing mean hospitalization duration, cost, and single-disease expense. The latter restrictions more profoundly affect critically ill patients who usually require longer hospitalization and incur higher medical costs than patients with milder presentations.[31,36] In Chinese emergency medicine, there is a common saying that reflects this phenomenon: “the front door to the ED is always open even if the back door into the hospital is closed”.

Beyond patient-provider relationships, the provision of high-quality emergency care is often hampered by lack of an adequate workforce, despite the increase of emergency physicians and nurses during the past ten years. Unlike the USA, the emergency physicians in China work alone without emergency technicians and physician extenders such as physician assistants in their teams. Because of a limited workforce managing an increasingly large population with longer admission time, mental and physical exhaustion remains a serious concern for the EMSS workforce, particularly in the larger hospitals of most regions.[27,37,38] The most acute situation in the fields of the EMSS raised concerns about emergency health workers’ endurance and shortages, and quality and efficiency of treating increasing numbers of emergency patients now and in the future.

To face the aforementioned challenges, which are rooted in a rapidly increasing demand against a backdrop of increasingly limited and strained acute care resources, the Chinese EMSS must evolve to advance the “Healthy China 2030” goals. Otherwise, the problems of Chinese EMSS may be more severe. Capabilities of hospitals and providers need to be improved to match the demands of acute care. This includes strengthening the quality improvement and residency training in county-level hospitals, encouraging junior physicians to select emergency care as a specialty career, and increasing medical assistants of EMSS. Broader and sustainable workforce development should be cultured based on policies, such as establishing a safe work environment and increasing available funding. However, it is not enough to only rely on self-directed initiatives by hospitals and medical staff. Public health authorities and the government should increase their focus on this matter. They should design and implement stronger and more efficient targeted plans in the context of broader medical reform, such as strengthening the construction of hierarchical medical treatment system, speeding up the reform of the medical insurance policies, setting up family doctor service system, and strengthening the service capabilities of regional medical centers. Moreover, it is also necessary to take steps to keep people healthier at home, and provide funding for social determinants of health, such as social workers for mental health patients and home care nurses to help with proper administration of medications. It is also necessary to monitor quality and outcomes. The establishment of a national electronic information system and a surveillance tracking system of outcomes in EMSS would be helpful to achieve this target. Encouragingly, China has been implementing some reforms, such as widespread residency training, hierarchical medical treatment system, diagnosis related group payment, general practitioner cultivation, and community health services of family physician model, which should benefit to address these challenges and improve Chinese EMSS.[39,40,41]

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past decade, the number of emergency visits has grown with continually enhancing capabilities. However, the overcrowding and the long length of stay in EDs, poor work environment, work exhaustion, and consequent staff instability are still the critical challenges faced by China’s EMSS. The study can provide new insights for promoting the quality of emergency care in China, and offer the Chinese experience to the world’s EMSS, especially to other developing countries in similar circumstances.

Funding: This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0908700, 2017YFC0908703); Taishan Young Scholar Program of Shandong Province (tsqn20161065, tsqn201812129); Taishan Pandeng Scholar Program of Shandong Province (tspd20181220); National S&T Fundamental Resources Investigation Project (2018FY100600, 2018FY100602); Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2019GSF108075, 2020SFXGFY03, 2017G006013, 2018GSF118003); and Qilu Young Scholar Program.

Ethical approval: Approval from an ethical review board of the hospital was obtained before commencing the study.

Conflicts of interest: The authors confirm that no conflict of interest or any financial relationship that relates to the content of the manuscript has been associated with this publication.

Contributors: FX and YGC had the original idea and designed the paper structure. CP and FX drafted the paper. CP, JJP, and KC reviewed the literature, collected the information, analyzed data, and prepared the references. CP produced the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Reference

Trends in mortality of emergency departments patients in China

URL PMID:31171945 [Cited within: 3]

Problems in emergency medicine system: why nobody wants to be an emergency staff

Latent crisis in overcrowding emergency departments

Emergency department characteristics and capabilities in Beijing, China

URL PMID:23473821 [Cited within: 1]

National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2008 emergency department summary tables

Emergency department enlargement in China: exciting or bothering

URL PMID:27162657 [Cited within: 3]

Analysis of current situation of Chinese health care reform by studying emergency overcrowding in a typical Shanghai hospital

URL PMID:22818562 [Cited within: 1]

Violence against doctors in China

URL PMID:25176547 [Cited within: 1]

Prehospital emergency talent team construction in China should be taken seriously

Investigation on hospital violence during 2003 to 2012 in China

The China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Registry: a national long-term registry-research-education integrated platform for exploring acute myocardial infarction in China

DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.014

URL

PMID:27179740

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has become a major cause of hospitalization and mortality in China. There has been limited data to date available to characterize AMI presentation, contemporary patterns of medical care, and outcomes in China. AIMS: The CAMI Registry is a national project with the objectives to timely obtain real-world knowledge about AMI patients and to provide the platform for clinical research, guide preventive measures and care quality improvement efforts in China. METHODS AND PROGRESS: The CAMI registry is a prospective, nationwide, multicenter observational study for AMI patients. The registry includes three levels of hospitals (representing typical Chinese governmental and administrative models) from all provinces and municipalities throughout Mainland China except Hong Kong and Macau. Sites were instructed to enroll consecutive patients with a primary diagnosis of AMI. Clinical data, treatments, outcomes and cost are collected by local investigators and captured electronically, with a standardized set of variables and standard definitions, and rigorous data quality control. Post-discharge patient follow-up to 2 years is planned. The CAMI Registry was launched in January 2013. A total of 108 hospitals have participated in the registry so far. As of September 2014, 26,103 patients with AMI were registered. CONCLUSIONS: The CAMI registry represents a well-supported and the largest national long-term registry-research-education platform for surveillance, research, prevention and care improvement for AMI in China, the world's most populous nation. The broad representation of all provinces and different-level hospitals will allow for the exploration of AMI across diverse geographic regions and economic circumstances.

Achieving best outcomes for patients with cardiovascular disease in China by enhancing the quality of medical care and establishing a learning health-care system

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00343-8

URL

PMID:26466053

[Cited within: 1]

China has an immediate need to address the rapidly growing population with cardiovascular disease events and the increasing number of people living with this illness. Despite progress in increasing access to services, China faces the dual challenge of addressing gaps in quality of care and producing more evidence to support clinical practice. In this Review, we address opportunities to strengthen performance measurement, programmes to improve quality of care, and national capacity to produce high-impact knowledge for clinical practice. Moreover, we propose recommendations, with implications for other diseases, for how China can immediately make use of its Hospital Quality-Monitoring System and other existing national platforms to assess and improve performance of medical care, and to generate new knowledge to inform clinical decisions and national policies.

National Hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2015 emergency department summary tables

Active physicians in the largest specialties

Job burnout among physicians in ten areas of China

URL

PMID:24548396

[Cited within: 2]

OBJECTIVE: To explore the status of job burnout among Chinese physicians and identify the risk factors for hospital human resource management. METHODS: A total of 510 physicians from 10 areas of China participated in the survey from July to October 2012. RESULTS: Among them, 84.9% reported medium or higher level of emotional exhaustion, 87.8% with moderate degree of depersonalization and 81.8% with at least moderate degree of diminished personal accomplishment. The degree of job burnout was higher among physicians who were unmarried (t = 2.12, P = 0.03; t = 2.06, P = 0.04) , under 10-year seniority (P = 0.03; P = 0.01) , working at tertiary hospitals (F = 2.34, P = 0.04) or emergency department (P < 0.05) . CONCLUSION: As a common phenomenon in China, job burnout among physicians should raise great concerns. Individual's marriage status, length of service, degree of education, hospital class and affiliated department should be considered when identification and intervention of physicians' job burnout are implemented.

Review article: burnout in emergency medicine physicians

DOI:10.1111/1742-6723.12135

URL

PMID:24118838

[Cited within: 2]

Training and the practice of emergency medicine are stressful endeavours, placing emergency medicine physicians at risk of burnout. Burnout syndrome is associated with negative outcomes for patients, institutions and the physician. The aim of this review is to summarise the available literature on burnout among emergency medicine physicians and provide recommendations for future work in this field. A search of MEDLINE (1946-present) (search terms: 'Burnout, Professional' AND 'Emergency Medicine' AND 'Physicians'; 'Stress, Psychological' AND 'Emergency Medicine' AND 'Physicians') and EMBASE (1988-present) (search terms: 'Burnout' AND 'Emergency Medicine' AND 'Physicians'; 'Mental Stress' AND 'Emergency Medicine' AND 'Physicians') was performed. The authors focused on articles that assessed burnout among emergency medicine physicians. Most studies used the Maslach Burnout Inventory to quantify burnout, allowing for cross-study (and cross-country) comparisons. Emergency medicine has burnout levels in excess of 60% compared with physicians in general (38%). Despite this, most emergency medicine physicians (>60%) are satisfied with their jobs. Both work-related (hours of work, years of practice, professional development activities, non-clinical duties etc.) and non-work-related factors (age, sex, lifestyle factors etc.) are associated with burnout. Despite the heavy burnout rates among emergency medicine physicians, little work has been performed in this field. Factors responsible for burnout among various emergency medicine populations should be determined, and appropriate interventions designed to reduce burnout.

The gap of prehospital emergency physician team is big in China: a hard situation to attract and retain prehospital emergency medical staff

Current situation analysis of medical talents in prehospital emergency system of Shanghai

EMS systems in China

DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.04.016

URL

PMID:19443099

[Cited within: 1]

The prehospital emergency service is the initial part of the Emergency Medical Service System (EMSS) in China, and is the de facto overall emergency medical service for China. As the EMSS in China continues to undergo rapid development, it faces the challenge of providing rapid response times with adequate coverage for this highly populated country. The recent Sichuan earthquake on 12 May 2008 tested the ability of the EMSS response. This article focuses on the prehospital emergency service of the EMSS and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the current system.

Shortage of paediatricians in China

URL PMID:24629297 [Cited within: 1]

Emergency medicine in China: present and future

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2011.04.001

URL

PMID:25215018

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Emergency medicine was inaugurated, as an official specialty in China, only 25 years ago, and its growth in clinical practice and academic development since that time have been remarkable. METHODS: This paper is a critical and descriptive review on current situations in emergency medicine in China, based on the literature review, personal observations, interviews with many Chinese emergency medicine doctors and experts, and personal experience in both China and USA. RESULTS: THE CURRENT PRACTICE OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE IN CHINA ENCOMPASSES THREE AREAS: pre-hospital medicine, emergency medicine, and critical care medicine. Most tertiary emergency departments (EDs) are structurally and functionally divided into several clinical areas, allowing the ED itself to function as a small independent hospital. While Chinese emergency physicians receive specialty training through a number of pathways, national standards in training and certification have not yet been developed. As a result, the scope of practice for emergency physicians and the quality of clinical care vary greatly between individual hospitals. Physician recruitment, difficult working conditions, and academic promotion remain as major challenges in the development of emergency medicine in China. CONCLUSION: To further strengthen the specialty advancement, more government leadership is needed to standardize regional training curriculums, elucidate practice guidelines, provide funding opportunities for academic development in emergency medicine, and promote the development of a system approach to emergency care in China.

Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013

URL PMID:26510778 [Cited within: 1]

Hospital-based emergency departments: background and policy considerations

Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43812.pdf.

Emergency medicine in China: redefining a specialty

DOI:10.1016/s0736-4679(01)00372-9

URL

PMID:11489414

[Cited within: 1]

The People's Republic of China (PRC) is developing a unique system of emergency medical facilities based on its own conditions, adapting elements of both North American and European models, as well as creating some of its own. This ongoing evolution of a system for provision of emergency medical care reflects a society that is itself in rapid transition. There have been great strides in the advancement of this specialty over the last two decades. China now has an Emergency Medicine (EM) association, training programs, and specialty journals. Nevertheless, although an organizational framework now exists, development of EM in China as a whole can be said to be at an early stage. The number of trained practitioners is still small, and EMS providers are generally not trained or integrated except in a few large cities. By all estimates, the pace of growth of EM in China will continue to accelerate as China's economy and demographics approach those of the west, but the final form they will take is still uncertain.

The emergency department in China: status and challenges

DOI:10.1136/emermed-2012-202305 URL PMID:23413150 [Cited within: 2]

Emergency department overcrowding: analysis and strategies to manage an international phenomenon

URL PMID:33296025 [Cited within: 1]

Overcrowding in emergency department: an international issue

DOI:10.1007/s11739-014-1154-8

URL

PMID:25446540

Overcrowding in the emergency department (ED) has become an increasingly significant worldwide public health problem in the last decade. It is a consequence of simultaneous increasing demand for health care and a deficit in available hospital beds and ED beds, as for example it occurs in mass casualty incidents, but also in other conditions causing a shortage of hospital beds. In Italy in the last 12-15 years, there has been a huge increase in the activity of the ED, and several possible interventions, with specific organizational procedures, have been proposed. In 2004 in the United Kingdom, the rule that 98 % of ED patients should be seen and then admitted or discharged within 4 h of presentation to the ED ('4 h rule') was introduced, and it has been shown to be very effective in decreasing ED crowding, and has led to the development of further acute care clinical indicators. This manuscript represents a synopsis of the lectures on overcrowding problems in the ED of the Third Italian GREAT Network Congress, held in Rome, 15-19 October 2012, and hopefully, they may provide valuable contributions in the understanding of ED crowding solutions.

Burnout syndrome among emergency medicine physicians: an update on its prevalence and risk factors

DOI:10.26355/eurrev_201910_19308

URL

PMID:31696496

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: Training in and practising emergency medicine are very stressful conditions that pose a significant emotional burden on physicians, placing them at high risk of developing burnout. The purpose of the current manuscript is to review the published literature on burnout prevalence among emergency medicine physicians and to identify the risk factors associated with its occurrence. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A search of MEDLINE (January 1980-March 2019) was conducted using the terms

A new medical safety factor for critical patients: emergency department overcrowding

Emergency care in 59 low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review

DOI:10.2471/BLT.14.148338

URL

PMID:26478615

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To conduct a systematic review of emergency care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). METHODS: We searched PubMed, CINAHL and World Health Organization (WHO) databases for reports describing facility-based emergency care and obtained unpublished data from a network of clinicians and researchers. We screened articles for inclusion based on their titles and abstracts in English or French. We extracted data on patient outcomes and demographics as well as facility and provider characteristics. Analyses were restricted to reports published from 1990 onwards. FINDINGS: We identified 195 reports concerning 192 facilities in 59 countries. Most were academically-affiliated hospitals in urban areas. The median mortality within emergency departments was 1.8% (interquartile range, IQR: 0.2-5.1%). Mortality was relatively high in paediatric facilities (median: 4.8%; IQR: 2.3-8.4%) and in sub-Saharan Africa (median: 3.4%; IQR: 0.5-6.3%). The median number of patients was 30 000 per year (IQR: 10 296-60 000), most of whom were young (median age: 35 years; IQR: 6.9-41.0) and male (median: 55.7%; IQR: 50.0-59.2%). Most facilities were staffed either by physicians-in-training or by physicians whose level of training was unspecified. Very few of these providers had specialist training in emergency care. CONCLUSION: Available data on emergency care in LMICs indicate high patient loads and mortality, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where a substantial proportion of all deaths may occur in emergency departments. The combination of high volume and the urgency of treatment make emergency care an important area of focus for interventions aimed at reducing mortality in these settings.

Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients

Emergency department overcrowding, mortality and the 4-hour rule in Western Australia

DOI:10.5694/mja11.11159

URL

PMID:22304606

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To assess whether emergency department (ED) overcrowding was reduced after the introduction of the 4-hour rule in Western Australia and whether any changes in overcrowding were associated with significant changes in patient mortality rates. DESIGN, SETTING AND PATIENTS: Quasi-experimental intervention study using dependent pretest and post-test samples. Hospital and patient data were obtained for three tertiary hospitals and three secondary hospitals in Perth, WA, for 2007-08 to 2010-11. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Mortality rates; overcrowding rates. RESULTS: No change was shown in mortality from 2007-08 to 2010-11 for the secondary hospitals and from 2007-08 to 2009-10 for the tertiary hospitals. ED overcrowding (as measured by 8-hour access block) at the tertiary hospitals improved dramatically, falling from above 40% in July 2009 to around 10% by early 2011, and presentations increased by 10%, while the mortality rate fell significantly (by 13%; 95% CI, 7%-18%; P < 0.001) from 1.12% to 0.98% between 2009-10 and 2010-11. Monthly mortality rates decreased significantly in two of the three tertiary hospitals concurrently with decreased access block and an increased proportion of patients admitted in under 4 hours. CONCLUSION: Introduction of the 4-hour rule in WA led to a reversal of overcrowding in three tertiary hospital EDs that coincided with a significant fall in the overall mortality rate in tertiary hospital data combined and in two of the three individual hospitals. No reduction in adjusted mortality rates was shown in three secondary hospitals where the improvement in overcrowding was minimal.

Emergency, anaesthetic and essential surgical capacity in the Gambia

DOI:10.2471/BLT.11.086892

URL

PMID:21836755

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To assess the resources for essential and emergency surgical care in the Gambia. METHODS: The World Health Organization's Tool for Situation Analysis to Assess Emergency and Essential Surgical Care was distributed to health-care managers in facilities throughout the country. The survey was completed by 65 health facilities - one tertiary referral hospital, 7 district/general hospitals, 46 health centres and 11 private health facilities - and included 110 questions divided into four sections: (i) infrastructure, type of facility, population served and material resources; (ii) human resources; (iii) management of emergency and other surgical interventions; (iv) emergency equipment and supplies for resuscitation. Questionnaire data were complemented by interviews with health facility staff, Ministry of Health officials and representatives of nongovernmental organizations. FINDINGS: Important deficits were identified in infrastructure, human resources, availability of essential supplies and ability to perform trauma, obstetric and general surgical procedures. Of the 18 facilities expected to perform surgical procedures, 50.0% had interruptions in water supply and 55.6% in electricity. Only 38.9% of facilities had a surgeon and only 16.7% had a physician anaesthetist. All facilities had limited ability to perform basic trauma and general surgical procedures. Of public facilities, 54.5% could not perform laparotomy and 58.3% could not repair a hernia. Only 25.0% of them could manage an open fracture and 41.7% could perform an emergency procedure for an obstructed airway. CONCLUSION: The present survey of health-care facilities in the Gambia suggests that major gaps exist in the physical and human resources needed to carry out basic life-saving surgical interventions.

Prolonged length of stay in the emergency department in high-acuity patients at a Chinese tertiary hospital

URL PMID:23216724 [Cited within: 1]

Emergency medicine in China: current situation and its future development

DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2012.07.011 URL PMID:23000331 [Cited within: 1]

Psychological distress, burnout level and job satisfaction in emergency medicine: a cross-sectional study of physicians in China

URL PMID:25319720 [Cited within: 1]

China’s new 4 + 4 medical education programme

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32178-6 URL PMID:31571588 [Cited within: 1]

10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage

URL PMID:31571602 [Cited within: 1]

Transformation of the education of health professionals in China: progress and challenges

DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61307-6

URL

PMID:25176552

[Cited within: 1]

In this Review we examine the progress and challenges of China's ambitious 1998 reform of the world's largest health professional educational system. The reforms merged training institutions into universities and greatly expanded enrolment of health professionals. Positive achievements include an increase in the number of graduates to address human resources shortages, acceleration of production of diploma nurses to correct skill-mix imbalance, and priority for general practitioner training, especially of rural primary care workers. These developments have been accompanied by concerns: rapid expansion of the number of students without commensurate faculty strengthening, worries about dilution effect on quality, outdated curricular content, and ethical professionalism challenged by narrow technical training and growing admissions of students who did not express medicine as their first career choice. In this Review we underscore the importance of rebalance of the roles of health sciences institutions and government in educational policies and implementation. The imperative for reform is shown by a looming crisis of violence against health workers hypothesised as a result of many factors including deficient educational preparation and harmful profit-driven clinical practices.