INTRODUCTION

Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders are intended to allow patients to forgo cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of cardiopulmonary arrest. Patients who choose this option may also forgo extra life-sustaining interventions,[1,2] which does not imply withholding or withdrawing all other treatments or interventions.[3] A DNR order is thought to be an important part of advance directive (AD) in patients near the end of life,[4] and has become a part of the society’s ritual for dying.[5] A signed DNR order has been gaining popularity worldwide with the development of hospice care. However, there is no legal guarantee of a signed DNR order for patients in the Chinese mainland.[6] It is regarded as valuable in helping patients to be treated with dignity in their last days.[4] Signing a DNR order is currently a common practice in many countries. A DNR order indicates that the patient refuses basic or advanced life support that would delay death;[7,8] it can also be written to avoid futile treatment and resuscitation while continuing appropriate symptom-attenuated treatment.[9,10] The concept of the DNR order evokes controversy regarding the appropriate care for dying patients and has received considerable attention from emergency medical staff.

Emergency departments (EDs) provide physical and psychological treatments for patients with severe diseases or terminal illnesses.[11,12] Death frequently occurs in EDs.[13] Recent evidence indicates that half of the elderly patients visited the emergency room in the last month of their lives.[14] Chan [15] reported that patients came to EDs with unexpected injuries, chronic disease exacerbations, or perhaps terminal illnesses seeking life-saving or life-prolonging treatment. Aggressive invasive treatment and life-prolonging strategies are usually prioritized due to complications and rapid changes in patients’ conditions. Life-sustaining active treatments are sometimes regarded as futile for those with incurable or terminal illness, although they may prolong the patient’s lives.[11,16] Patients consenting to DNR were often able to avoid futile examination and invasive rescue measures, to alleviate suffering and maintain their dignity.[17]

Signing a DNR consent form is an important medical decision-making process; early initiation of discussions can improve end-of-life care and reduce futile treatments in EDs.[11] In China, many families object to revealing about an incurable diagnosis or poor disease prognosis to patients, which may impede the end-of-life care-related decisions. Studies show that Chinese patients may leave their end-of-life care-related decisions, such as receiving life-sustaining therapy or signing DNR directives, to family members.[18] However, making these decisions is difficult for physicians and family surrogates, and depends on ethical issues associated with legal, moral, cultural, and religious values.[19,20] The medical staff often have little information about patients’ wishes and have no previous relationship with them.[14] Several studies on DNR in the acute care setting have been reported in intensive care units (ICUs). To our knowledge, this remains the first pilot study on the implementation of DNR directives to patients at their end-of-life in EDs in the Chinese mainland.

This study aimed to describe the clinical characteristics of patients who died in EDs, to investigate the signing of DNR orders, and to analyze the related factors.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a retrospective chart study conducted in an adult ED, in a tertiary university-affiliated hospital from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2019. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (IRB number: IR2020001036). Personal informed consent was not required.

Selection of participants

The inclusion criteria were adult patients who died in an ED after being admitted. The exclusion criteria were patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Patients were required to be ≥18 years old and had at least one immediate family member present during the ED stay. The immediate family members needed to be ≥18 years old and acted as the primary family caregivers and patients’ surrogates.

The DNR order was defined as a complete and formal DNR discussion between emergency medical staff and family surrogates, after which a form was signed by the physician and the surrogate.

Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire designed by the investigator. The collected variables from each patient’s electronic medical records were guided by the literature review. Demographic information included age, sex, medical insurance, place of residence, and duration from morbidity to DNR signing. Triage information contained the number of referrals, ambulance transfer, 30-day readmission, triage classification, and the clinical department. Disease-related information included disease diagnosis and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Invasive operation information included tracheal intubation, invasive mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, electric cardioversion, central venous catheter, indwelling gastric tube, and indwelling catheter. Death information included the time of death, death trajectory, and ED length of stay (ED LOS). The ED LOS was defined as the time between emergency admission and patient death, in hours. A complete and formal DNR discussion, a record of a signature by the patient or their family surrogates, and the time of death were included with the signed DNR order.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using SPSS software (version 25). Parametric data were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD), and differences between groups were assessed using a t-test. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to test for differences between groups for nonparametric distribution data, and the results were presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR). The categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage and analyzed by the Chi-squared test. Factors associated with signing DNR orders were examined using univariate analysis, and those with significant differences were used for multivariate analysis. The strength of association was indicated by the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). P<0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients who died in the ED

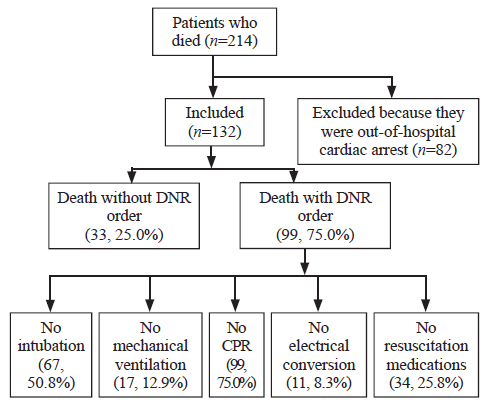

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial profile of 214 patients admitted to emergency department during the study period.

Table 1 Demographic and pre-hospital information of the 132 patients who died in ED

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 77 (55.25, 87.75) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 88 (66.7) |

| Female | 44 (33.3) |

| Living of place | |

| Countryside | 21 (15.9) |

| City | 111 (84.1) |

| Expense category | |

| Self-supporting | 35 (26.5) |

| Medical insurance | 97 (73.5) |

| Duration from morbidity to signing DNR (hours), median (IQR) | 14 (2, 42) |

| Pre-hospital information | |

| Referral | |

| No | 91 (68.9) |

| Yes | 41 (31.1) |

| 30-day readmission | |

| Yes | 54 (40.9) |

| No | 78 (59.1) |

| Ambulance transfer | |

| Yes | 108 (81.8) |

| No | 24 (18.2) |

| Triage | |

| Level I | 73 (55.3) |

| Level II | 31 (23.5) |

| Level III | 21 (15.9) |

| Level IV | 2 (1.5) |

| Level V | 5 (3.8) |

| Clinical department | |

| Internal medicine | 61 (46.2) |

| Neurology department | 37 (28.0) |

| Cardiology department | 11 (8.3) |

| Emergency department | 10 (7.6) |

| Neurosurgery department | 8 (6.1) |

| Surgical department | 5 (3.8) |

ED: emergency department; IQR: interquartile range; data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of the 132 patients who died in ED

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| CCI (mean±SD) | 4.39±2.61 |

| ED LOS (hours), median (IQR) | 25.50 (10.25, 83.50) |

| Acute medical disorders | |

| ACVD | 44 (33.3) |

| AHDT | 10 (7.6) |

| Shock | 10 (7.6) |

| Multiple trauma | 9 (6.8) |

| AMI | 5 (3.8) |

| Toxicosis | 4 (3.0) |

| AECOPD | 2 (1.5) |

| Chronic underlying diseases | |

| Malignancy | 26 (19.7) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 24 (18.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 17 (12.9) |

| Chronic renal disease | 11 (8.3) |

| Chronic liver disease | 10 (7.6) |

| Dementia | 4 (3.0) |

| Organ failures | |

| Respiratory failure | 17 (12.9) |

| Renal insufficiency | 15 (11.4) |

| Heart failure (NYHA class 4) | 14 (10.6) |

| Hepatic insufficiency | 8 (6.1) |

| Main medical disorders | |

| Neurological | 49 (37.1) |

| Cardiovascular | 27 (20.5) |

| Respiratory | 27 (20.5) |

| Cancer | 26 (19.7) |

| Infectious | 24 (18.2) |

| Digestive | 16 (12.1) |

| Traumatic | 9 (6.8) |

| Death trajectory | |

| Frailty | 45 (34.1) |

| Sudden death | 42 (31.8) |

| Organ failure | 25 (18.9) |

| Terminal illness | 20 (15.2) |

CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ED LOS: emergency department length of stay; ACVD: acute cerebrovascular disease; AHDT: acute hemorrhage of digestive tract; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; AECOPD: acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Patient management in the ED

The frequent modalities of invasion operation were indwelling catheter for 77 (58.3%) patients, invasive mechanical ventilation for 53 (40.2%) patients, cardiopulmonary resuscitation for 33 (25.0%) patients, electric cardioversion for 2 (1.5%) patients, central venous catheter for 20 (15.2%) patients, indwelling gastric tube for 24 (18.2%) patients, and tracheal intubation for 54 (40.9%) patients. Of the 99 (75.0%) cases with a DNR order, 97 were from family surrogates, and only two made their own decisions. The most frequent orders were: no cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for 99 (75.0%) patients, no intubation for 67 (50.8%) patients, no resuscitation medications for 34 (25.8%) patients, and no mechanical ventilation for 17 (12.9%) patients (Figure 1). Sixty-four (64.6%) cases consented the DNR within 24 hours of the ED admission, and 68 (68.7%) patients died within 24 hours after consenting.

Comparison of the characteristics between patients with and without DNR

DNR patients were elderly, lived in cities, and had medical insurance (Table 3). Patients who consented DNR also used less tracheal intubation or invasive mechanical ventilation (P<0.001). The results also showed that patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were less likely to sign DNR orders (P=0.018), and patients with DNRs had higher CCI (P=0.001) and more complications than patients without DNRs. The time from ED admission to death was significantly longer in the DNR group than in the non-DNR group (median: 29 hours and 12 hours, respectively, P=0.008).

Table 3 Comparison of characteristics between patients with DNR and without DNR, n (%)

| Variables | DNR (n=99) | Without DNR (n=33) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 82 (63, 89) | 59 (45, 73) | <0.001 |

| Male | 66 (66.7) | 22 (66.7) | 1.000 |

| City | 89 (89.9) | 22 (66.7) | 0.002 |

| Medical insurance | 82 (82.8) | 15 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| No referral | 76 (76.8) | 15 (45.5) | 0.001 |

| 30-day readmission | 40 (40.4) | 14 (42.4) | 0.838 |

| Ambulance transfer | 82 (82.2) | 26 (78.8) | 0.602 |

| Triage | 0.060 | ||

| Level I | 54 (54.5) | 19 (57.6) | |

| Level II | 27 (27.3) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Level III | 15 (15.2) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Level IV | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| Level V | 3 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | |

| CCI (mean±SD) | 4.83±2.49 | 3.06±2.55 | 0.001 |

| ED LOS (hours), median (IQR) | 29 (13, 99) | 12 (3, 59) | 0.008 |

| Trachea intubation | 26 (26.3) | 28 (84.8) | <0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 25 (25.3) | 28 (84.8) | <0.001 |

| Electric cardioversion | 0 (0) | 2 (6.1) | 0.061 |

| Central venous catheter | 13 (13.1) | 7 (21.2) | 0.400 |

| Indwelling gastric tube | 19 (19.2) | 5 (15.2) | 0.602 |

| Indwelling catheter | 57 (57.6) | 20 (60.6) | 0.760 |

| AMI | 1 (1.0) | 4 (12.1) | 0.018 |

| ACVD | 32 (32.3) | 12 (36.4) | 0.670 |

| AHDT | 9 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) | 0.447 |

| AECOPD | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Multiple trauma | 4 (4.0) | 5 (15.2) | 0.073 |

| Shock | 7 (7.1) | 3 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Toxicosis | 3 (3.0) | 1 (3.0) | 1.000 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12 (12.1) | 5 (15.2) | 0.881 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 19 (19.2) | 5 (15.2) | 0.602 |

| Malignancy | 22 (22.2) | 4 (12.1) | 0.206 |

| Liver disease | 9 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) | 0.447 |

| Renal disease | 8 (8.1) | 3 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Dementia | 4 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0.558 |

CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ED LOS: emergency department length of stay; ACVD: acute cerebrovascular disease; AHDT: acute hemorrhage of digestive tract; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; AECOPD: acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

Factors related to the DNR decision

Factors associated with DNR as determined using univariate analysis were: older age, living in a city, having medical insurance, no referral, CCI >3, ED LOS ≥72 hours, tracheal intubation, invasive mechanical ventilation, AMI, and trauma. Other variables did not correlate with the DNR decision directive (P>0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4 Influencing factors of DNR signing in emergency death patients (n=132)

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 1.045 | 1.022-1.068 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| Living in city | 4.450 | 1.678-11.801 | 0.003 | - | - | - |

| Medical insurance | 5.788 | 2.445-13.700 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| No referral | 0.252 | 0.110-0.578 | 0.001 | 0.157 | 0.047-0.529 | 0.003 |

| CCI >3 | 5.084 | 2.195-11.772 | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| ED LOS ≥72 hours | 3.152 | 1.018-9.757 | 0.046 | 5.889 | 1.290-26.885 | 0.022 |

| AMI | 0.074 | 0.008-0.688 | 0.022 | 0.017 | 0.001-0.279 | 0.004 |

| Traumatic | 0.236 | 0.059-0.938 | 0.040 | - | - | - |

| Trachea intubation | 0.064 | 0.022-0.182 | <0.000 | 0.028 | 0.007-0.120 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.060 | 0.021-0.173 | <0.000 | - | - | - |

CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ED LOS: emergency department length of stay; AMI: acute myocardial infarction.

Multivariate analysis was applied to factors found to be significant using univariate analysis. The multivariate analysis showed that no referral, ED LOS ≥72 hours, AMI, and tracheal intubation were significantly associated with DNR decision.

DISCUSSION

Acute internal diseases were the main reasons for ED admission. This finding was consistent with a previous study by Le Conte et al.[21] Patients who died had more complications in the ED. In our study, the average CCI score was 4.39, which was higher than that reported by Hsu et al.[22] The average ED LOS for patients who died in the ED was 25.5 hours in this study, which was higher than the results reported by Ye et al.[23] The reasons may be connected with the patients with more complicated conditions, diagnoses that involved multiple departments, or delayed admission to the ward.

In this cohort, 99 (75.0%) of the 132 patients in the ED had signed a DNR order before they died. Studies showed that 87.3% of patients signed DNR orders before death in America.[24] In the UK, there were about 160,000 hospital deaths annually, and 80% of patients died with a DNR order.[25] In Australia, 82% of patients signed a DNR before death.[26] By comparison, Chinese patients who died in the hospital had a lower DNR rate than those in developed countries. It is considered as blasphemous and disrespectful to mention death in Chinese traditional culture; this may result in avoidance of any discussion about death.[27] Decisions about DNR orders are usually made by family surrogates when the patients are severely ill.[6] Confucianism deeply influences Chinese tradition and culture;[28] the eldest son or daughter is regarded as their agent by most elderly patients. Filial piety strongly affects decision-making;[18] signing DNR directives was once considered to abandon life and wait for death, which was contrary to the traditional filial piety in China.

In our study, 97 (98.0%) patients had DNR signed by family surrogates, and only two patients made their own decisions. However, in Europe and North America, older patients prefer to make their final DNR directives.[17,29] The possible reasons are few ADs,[30] no anticipation about end-of-life decisions before admission in ED, and conversations between physicians and family surrogates at the last admission. Because of the lack of ADs, family members need to express patients’ wishes concerning their end-of-life preferences.[31] Kwok et al[32] found that most family surrogates had poor knowledge of life-sustaining treatments, and most of them depended on their views but not the patients’ wishes to make the final DNR directives. By tradition, the eldest son or daughter is obliged by filial piety to do everything to prolong the elderly patient’s life; the opinions of family members and health-care professionals take precedence over personal opinions or preferences.[18]

Previous studies reported a strong association between the presence of a DNR order and mortality.[17] In our study, we found that signing DNR orders on the day of the patients’ death was the most common (68.7%). Signing DNR order increased as death approached. Also, 64.6% (64/99) of the patients signed DNR directives within 24 hours after ED admission. Demographic data showed that the median duration from morbidity to DNR signing was 14 hours. These findings will help us better understand the importance of timing in the initiation of the DNR process in the ED. In clinical practice, patients with terminal illnesses or sudden devastating events usually have a poor prognosis, and emergency medical staff would communicate with patients or their family surrogates earlier. An early DNR order in the ED may indicate a person’s preference to restrict care because of particular beliefs and the state of their health.[33] Conversely, a DNR order singed after the first 24 hours (late DNR) in the ED may indicate that the individual does not respond to medical treatment,[33] so their families accept the fact that the patients are unable to wake up and be cured.

Four factors associated with executing a DNR by patients’ surrogates were identified: referral, ED LOS, AMI, and tracheal intubation. Patients who were not referred from local hospitals were more likely to sign DNR orders than those who were. This reason could be that the patients’ families usually insist on life-sustaining treatment if the patient is referred to the ED of an urban tertiary referral hospital in China. As mentioned above, the most important reasons to self-refer to an ED were health concerns and further examinations.[34]

ED LOS was a predictive factor for the DNR decision, which was similar to the result of the study by Cheng et al.[11] Patients whose family surrogates signed a DNR order tended to stay longer at the ED and increased overcrowding.[22] These DNR patients with more complex comorbidities and terminal illnesses were more likely to die in the ED; this is a questionable development as the ED is not the most appropriate place for adequate end-of-life care, which should take place in a quiet and peaceful area.[35] Previous studies reported similar findings.[15,36] Early discussions about DNR with family surrogates and persistent education about hospice care may help the patients receive hospice care in the last stage of life.[11]

One predictive factor explained that patients diagnosed with AMI weren’t inclined to sign DNR orders. Previous studies showed that ≤1% of AMI patients had DNR orders before hospital admission.[37] The predictive factor of DNR was found to be relevant to tracheal intubation. A possible explanation is that patients’ family surrogates who refused resuscitation usually also refused intubation. A previous study pointed out that do-not-intubate orders were generally accompanied by DNR orders.[38]

There were limitations to this study: (1) it was a retrospective study, and there were some incomplete data in the electronic medical records; (2) the relatives’ satisfaction levels and emotional state regarding the quality of care in the ED could not be measured; (3) it was performed in a single academic hospital, and the results may not be representative of the general situation in the Chinese mainland.

CONCLUSIONS

The DNR signing rate is lower in the Chinese mainland, with DNR consent forms almost exclusively signed by family surrogates in the ED. The decision on whether to attempt resuscitation is just one of many end-of-life decisions. Physicians and nurses are encouraged to have early discussions about end-of-life care with patients or their surrogates. DNR directives should be developed to improve end-of-life care quality and reduce futile medical interventions in the ED.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (IRB number: IR2020001036).

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Contributors: CQD proposed and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

Reference

The effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on physician decision-making

DOI:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50620.x

URL

PMID:12473020

[Cited within: 1]

The effect of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders on physicians' decisions to provide life-prolonging treatments other than cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for patients near the end of life was explored using a cross-sectional mailed survey. Each survey presented three patient scenarios followed by 10 treatment decisions. Participants were residents and attending physicians who were randomly assigned surveys in which all patient scenarios included or did not include a DNR order. Response to three case scenarios when a DNR order was present or absent were measured. Response from 241 of 463 physicians (52%) was received. Physicians agreed or strongly agreed to initiate fewer interventions when a DNR order was present versus absent (4.2 vs 5.0 (P =.008) in the first scenario; 6.5 vs 7.1 (P =.004) in the second scenario; and 5.7 vs 6.2 (P =.037) in the third scenario). In all three scenarios, patients with DNR orders were significantly less likely to be transferred to an intensive care unit, to be intubated, or to receive CPR. In some scenarios, the presence of a DNR order was associated with a decreased willingness to draw blood cultures (91% vs 98%, P =.038), central line placement (68% vs 80%, P =.030), or blood transfusion (75% vs 87%, P =.015). The presence of a DNR order may affect physicians' willingness to order a variety of treatments not related to CPR. Patients with DNR orders may choose to forgo other life-prolonging treatments, but physicians should elicit additional information about patients' treatment goals to inform these decisions.

The impact of early do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest

DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327

URL

[Cited within: 1]

Objectives: Among patients successfully resuscitated from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and admitted to California hospitals, we examined how the placement of a do not resuscitate (DNR) order in the first 24 h after admission was associated with patient care, procedures and inhospital survival. We further analyzed hospital and patient demographic factors associated with early DNR placement among patients admitted following OHCA.

Methods: We identified post-OHCA patients from a statewide California database of hospital admissions from 2002 to 2010. Documentation of patient and hospital demographics, hospital interventions, and patient outcome were analyzed by descriptive statistics and multiple regression models to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Results: Of 5212 patients admitted to California hospitals after resuscitation from OHCA, 1692 (32.5%) had a DNR order placed in the first 24 h after admission. These patients had decreased frequency of cardiac catheterization (1.1% vs. 4.3%), blood transfusion (7.6% vs. 11.2%), ICD placement (0.1% vs. 1.1%), and survival to discharge (5.2% vs. 21.6%, all p-values <0.0001). There was wide intrahospital variability and significant racial differences in the adjusted odds of early DNR orders (Asian, OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.48-0.95; Black, OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.35-0.69).

Conclusions: Early DNR placement is associated with a decrease in potentially critical hospital interventions, procedures, and survival to discharge, and wide variability in practice patterns between hospitals. In the absence of prior patient wishes, DNR placement within 24 h may be premature given the lack of early prognostic indicators after OHCA. (C) 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd.

The “do-not-resuscitate” order in palliative surgery: ethical issues and a review on policy in Hong Kong

DOI:10.1017/S1478951514001370

URL

PMID:26399748

[Cited within: 1]

A do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, or

Determinants of do-not-resuscitate orders in palliative home care

DOI:10.1089/jpm.2007.0105

URL

PMID:18333737

[Cited within: 2]

OVERVIEW: Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders allow home care clients to communicate their own wishes over medical treatment decisions, helping to preserve their dignity and autonomy. To date, little is known about DNR orders in palliative home care. Basic research to identify rates of completion and determinants of DNR orders has yet to be examined in palliative home care. PURPOSE: The purpose of this exploratory study was to determine who in palliative home care has a DNR order as part of their advance directive. METHODS: Information on health was collected using the interRAI instrument for palliative care (interRAI PC). The sample included 470 home care clients from one community care access centre in Ontario. RESULTS: This study indicated that a preference to die at home (odds ratio [OR]: 8.29, confidence interval [CI]: 4.55-15.11); close proximity to death (OR: 0.99, CI: 0.99-1.00); daily incontinence (OR: 2.74, CI: 1.05-7.16); and sleep problems (OR: 1.85, CI: 1.02-3.37) are associated with DNR orders. In addition, clients who are more accepting of their situation are 5.67 times (CI: 1.67-19.27) more likely to have a DNR in place. CONCLUSION: This study represents an important first step to identifying issues related to DNR orders. In addition to proximity to death, incontinence, and sleep problems, acceptance of one's own situation and a preference to die at home are important determinants of DNR completion. The results imply that these discussions might often depend not only on the health of the clients but also on the clients' acceptance of their current situation and where they wish to die.

The DNR order after 40 years

DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1605597 URL PMID:27509098 [Cited within: 1]

The do-not-resuscitate order for terminal cancer patients in the Chinese mainland: a retrospective study

DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000010588

URL

PMID:29718859

[Cited within: 2]

With the development of palliative care, a signed do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order has become increasingly popular worldwide. However, there is no legal guarantee of a signed DNR order for patients with cancer in mainland China. This study aimed to estimate the status of DNR order signing before patient death in the cancer center of a large tertiary affiliated teaching hospital in western China. Patient demographics and disease-related characteristics were also analyzed.This was a retrospective chart analysis. We screened all charts from a large-scale tertiary teaching hospital in China for patients who died of cancer from January 2010 to February 2015. Analysis included a total of 365 records. The details of DNR order forms, patient demographics, and disease-related characteristics were recorded.The DNR order signing rate was 80%. Only 2 patients signed the DNR order themselves, while the majority of DNR orders were signed by patients' surrogates. The median time for signing the DNR order was 1 day before the patients' death. Most DNR decisions were made within the last 3 days before death. The time at which DNR orders were signed was related to disease severity and the rate of disease progression.Our findings indicate that signing a DNR order for patients with terminal cancer has become common in mainland China in recent years. Decisions about a DNR order are usually made by patients' surrogates when patients are severely ill. Palliative care in mainland China still needs to be improved.

Do-not-resuscitate decisions in six European countries

DOI:10.1097/01.CCM.0000218417.51292.A7

URL

PMID:16625128

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To study and compare the incidence and main background characteristics of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) decision making in six European countries. DESIGN: Retrospective. SETTING: We studied DNR decisions simultaneously in Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Italy (four regions), the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland (German-speaking part). In each country, random samples of death certificates were drawn from death registries to which all deaths are reported. The deaths occurred between June 2001 and February 2002. PARTICIPANTS: Reporting physicians received a mailed questionnaire about the medical decision making that had preceded death. The response percentage was 75% for the Netherlands, 67% for Switzerland, 62% for Denmark, 61% for Sweden, 59% for Belgium, and 44% for Italy. The total number of deaths studied was 20,480. INTERVENTIONS: None. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: Measurements were frequency of DNR decisions, both individual and institutional, and patient involvement. Before death, an individual DNR decision was made in about 50-60% of all nonsudden deaths (Switzerland 73%, Italy 16%). The frequency of institutional decisions was highest in Sweden (22%) and Italy (17%) and lowest in Belgium (5%). DNR decisions are discussed with competent patients in 10-84% of cases. In the Netherlands patient involvement rose from 53% in 1990 to 84% in 2001. In case of incompetent patients, physicians bypassed relatives in 5-37% of cases. CONCLUSIONS: Except in Italy, DNR decisions are a common phenomenon in these six countries. Most of these decisions are individual, but institutional decisions occur frequently as well. In most countries, the involvement of patients in DNR decision making can be improved.

Advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders among patients with terminal cancer in palliative care units in Japan: a nationwide survey

DOI:10.1177/1049909112462860

URL

PMID:23064036

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To examine the current status of advance directives (ADs) and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders among patients with terminal cancer in palliative care units (PCUs) in Japan. METHODS: We conducted a retrospective chart review of the last 3 consecutive patients who died in 203 PCUs before November 30, 2010. RESULTS: The percentages of patients who had ADs during the final hospitalization for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, intravenous fluid administration, tube feeding, antibiotic administration, and who had appointed a health care proxy were 47%, 46%, 42%, 19%, 18%, and 48%, respectively. Seventy-six percent of the patients had a DNR order. Of the patients with decision-making capacity, 68% were involved in the DNR decision. CONCLUSIONS: These findings may reflect positive changes in patients' attitudes toward ADs, in Japan.

Outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and estimation of healthcare costs in potential “do not resuscitate” cases

DOI:10.18295/squmj.2016.16.01.006

URL

PMID:26909209

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVES: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a life-saving procedure which may fail if applied unselectively. 'Do not resuscitate' (DNR) policies can help avoid futile life-saving attempts among terminally-ill patients. This study aimed to assess CPR outcomes and estimate healthcare costs in potential DNR cases. METHODS: This retrospective study was carried out between March and June 2014 and included 50 adult cardiac arrest patients who had undergone CPR at Sultan Qaboos Hospital in Salalah, Oman. Medical records were reviewed and treating teams were consulted to determine DNR eligibility. The outcomes, clinical risk categories and associated healthcare costs of the DNR candidates were assessed. RESULTS: Two-thirds of the potential DNR candidates were >/=60 years old. Eight patients (16%) were in a vegetative state, 39 (78%) had an irreversible terminal illness and 43 (86%) had a low likelihood of successful CPR. Most patients (72%) met multiple criteria for DNR eligibility. According to clinical risk categories, these patients had terminal malignancies (30%), recent massive strokes (16%), end-stage organ failure (30%) or were bed-bound (50%). Initial CPR was unsuccessful in 30 patients (60%); the remaining 20 patients (40%) were initially resuscitated but subsequently died, with 70% dying within 24 hours. These patients were ventilated for an average of 5.6 days, with four patients (20%) requiring >15 days of ventilation. The average healthcare cost per patient was USD $1,958.9. CONCLUSION: With careful assessment, potential DNR patients can be identified and futile CPR efforts avoided. Institutional DNR policies may help to reduce healthcare costs and improve services.

Discharge patterns, survival outcomes, and changes in clinical management of hospitalized adult patients with cancer with a do-not-resuscitate order

DOI:10.1089/jpm.2013.0554

URL

[Cited within: 1]

Background: Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders prevent medically futile attempts at resuscitation but are not always instituted in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. One explanation for this underuse is the perception that DNR orders are inevitably associated with withdrawal of all medical interventions and inpatient death.

Objectives: To audit discharge and survival outcomes and changes in clinical management in hospitalized adult oncology patients with a DNR order, allowing an assessment of whether such orders lead to cessation of acute interventions and high rates of in-hospital death.

Methods: Retrospective data were collected from 270 oncology inpatients at Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia, between February 1, 2012 and November 30, 2012.

Results: Mean and median time to institution of DNR orders after admission were 2.1 and 1.0 days, respectively (interquartile range, 0-2 days). Medical interventions continued in 80% or more of cases after DNR orders were placed included blood draws, intravenous antimicrobials, imaging, blood products, and radiotherapy. Two-thirds of patients survived hospitalization and were discharged alive. Survival at 30 days and 90 days after DNR orders were implemented was 63% and 33%, respectively. Baseline Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 5 or less and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2 or less were associated with a higher probability of being discharged alive and longer overall survival.

Conclusions: Most medical interventions were continued with high frequency in adult oncology inpatients after placement of DNR orders. A majority of patients survived hospitalization and remained alive at 30 days after DNR orders were documented. This study offers some reassurance that DNR orders do not inevitably lead to cessation of appropriate medical treatment.

Do-not-resuscitate orders and related factors among family surrogates of patients in the emergency department

DOI:10.1007/s00520-015-2971-7

URL

PMID:26514563

[Cited within: 5]

PURPOSE: The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and to identify relevant factors influencing the DNR decision-making process by patients' surrogates in the emergency department (ED). METHODS: A prospective, descriptive, and correlational research design was adopted. A total of 200 surrogates of cancer or non-cancer terminal patients, regardless of whether they signed a DNR order, were recruited as subjects after physicians of the emergency department explained the patient's conditions, advised on withholding medical treatment, and provided information on palliative care to all surrogates. RESULTS: Of the 200 surrogates, 23 % signed a DNR order for the patients. The demographic characteristics of patients and surrogates, the level of understanding of DNR orders, and factors of the DNR decision had no significant influence on the DNR decision. However, greater severity of disease (odds ratio (OR) = 1.38; 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 0.95-1.74), physician's initiative in discussing with the families (OR = 1.42; 95 % CI = 1.21-1.84), and longer length of hospital stay (OR = 1.06; 95 % CI = 1.03-1.08) were contributing factors affecting patient surrogates' DNR decisions. CONCLUSIONS: The findings of this study indicated that surrogates of patients who were more severe in disease condition, whose physicians initiated the discussion of palliative care, and who stayed longer in hospital were important factors affecting the surrogates' DNR decision-making. Therefore, early initiation of DNR discussions is suggested to improve end-of-life care.

A pilot trial to increase hospice enrollment in an inner city, academic emergency department

DOI:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.03.018

URL

PMID:27298266

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Hospice is underutilized, with over 25% of enrolled patients receiving hospice care for 3 days or less. The inner city emergency department (ED) is a highly trafficked area for patients in the last 6 months of life, and is a potential location for identification of hospice-eligible patients and early palliative care (PC) intervention. OBJECTIVES: We evaluated the feasibility of an ED PC intervention to identify hospice-eligible patients to accelerate PC consultation and hospice enrollment. METHODS: This prospective, pilot study established a program in the ED via education and a direct line of communication between the ED and PC to identify hospice-eligible patients, with the goal of facilitating disposition to hospice within 24 h. Data were analyzed for time to PC consultation, length of stay, emergency physician (EP) appropriateness of referral, and time from hospitalization to mortality. RESULTS: In a 6-month period, EPs identified 88 hospice-eligible patients with 91% accuracy. Of the patients identified, 59% died within 3 months of their visit to the ED. Time to PC consultation was 2.3 days (SD 2.3), and 57% of those seen by PC were discharged to hospice, vs. 30% of those not consulted (p = 0.038). The potential median hospice length of stay was 31.5 days, better than for the institution as a whole. CONCLUSIONS: Our pilot study presents a unique approach to early identification and disposition of hospice-appropriate patients, and suggests EPs may have sufficient prognostic accuracy to perform this task.

Death in the emergency department

DOI:10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70378-1 URL PMID:10036386 [Cited within: 1]

The POLST paradox: opportunities and challenges in honoring patient end-of-life wishes in the emergency department

DOI:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.021

URL

PMID:30503382

[Cited within: 2]

Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment forms convert patient wishes into physician orders to direct care patients receive near the end of life. Recent evidence of the challenges and opportunities for honoring patient end-of-life wishes in the emergency department (ED) is presented. The forms can be very helpful in directing whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intubation are desired in the first few minutes of a patient's presentation. After initial stabilization, understanding the intent of end-of-life orders and the scope of further interventions requires discussion with the patient or a surrogate. The emergency medicine provider must be committed both to honoring initial resuscitation orders and to the conversations required to narrow the gap between ED care and patient wishes so that people receive care best aligned with their wishes.

End-of-life models and emergency department care

DOI:10.1197/j.aem.2003.07.019

URL

PMID:14709435

[Cited within: 2]

Many people die in emergency departments (EDs) across the United States from sudden illnesses or injuries, an exacerbation of a chronic disease, or a terminal illness. Frequently, patients and families come to the ED seeking lifesaving or life-prolonging treatment. In addition, the ED is a place of transition-patients usually are transferred to an inpatient unit, transferred to another hospital, or discharged home. Rarely are patients supposed to remain in the ED. Currently, there is an increasing amount of literature related to end-of-life care. However, these end-of-life care models are based on chronic disease trajectories and have difficulty accommodating sudden-death trajectories common in the ED. There is very little information about end-of-life care in the ED. This article explores ED culture and characteristics, and examines the applicability of current end-of-life care models.

Attitudes towards ethical problems in critical care medicine: the Chinese perspective

DOI:10.1007/s00134-010-2124-x

URL

PMID:21264669

[Cited within: 1]

INTRODUCTION: Critical care doctors are frequently faced with clinical problems that have important ethical and moral dimensions. While Western attitudes and practice are well documented, little is known of the attitudes or practice of Chinese critical care doctors. METHODS: An anonymous, written, structured questionnaire survey was translated from previously reported ethical surveys used in Europe and Hong Kong. A snowball method was used to identify 534 potential participants from 21 regions in China. RESULTS: A total of 315 (59%) valid responses were analysed. Most respondents (66%) reported that admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) was commonly limited by bed availability, but most (63%) would admit patients with a poor prognosis to ICU. Only 19% of respondents gave complete information to patients and family, with most providing individually adjusted information, based on prognosis and the recipient's educational level. Only 28% disclosed all details of an iatrogenic incident, despite 62% stating that they should. The use of do not resuscitate orders or limitation of life-sustaining therapy in terminally ill patients reported as uncommon and according to comparable reports, both are more common practice in Hong Kong or Europe. In contrast to European practices, doctors were more acquiescent to families in decision-making at the end of life. CONCLUSIONS: A number of differences in ethical attitudes and related behaviour between Chinese, Hong Kong and European ICU doctors were documented. A likely explanation is differing cultural background, and doctors should be aware of likely expectations when treating patients from a different culture.

Do-not-resuscitate orders in older adults during hospitalization: a propensity score-matched analysis

DOI:10.1111/jgs.15347

URL

PMID:29676777

[Cited within: 3]

OBJECTIVES: To explore the effect of the presence and timing of a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order on short-term clinical outcomes, including mortality. DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study with propensity score matching to enable direct comparison of DNR and no-DNR groups. SETTING: Large, academic tertiary-care center. PARTICIPANTS: Hospitalized medical patients aged 65 and older. MEASUREMENTS: Primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included discharge disposition, length of stay, 30-day readmission, restraints, bladder catheters, and bedrest order. RESULTS: Before propensity score matching, the DNR group (n=1,347) was significantly older (85.8 vs 79.6, p<.001) and had more comorbidities (3.0 vs 2.5, p<.001) than the no-DNR group (n=9,182). After propensity score matching, the DNR group had significantly longer stays (9.7 vs 6.0 days, p<.001), were more likely to be discharged to hospice (6.5% vs 0.7%, p<.001), and to die (12.2% vs 0.8%, p<.001). There was a significant difference in length of stay between those who had a DNR order written within 24 hours of admission (early DNR) and those who had a DNR order written more than 24 hours after admission (late DNR) (median 6 vs 10 days, p<.001). Individuals with early DNR were less likely to spend time in intensive care (10.6% vs 17.3%, p=.004), receive a palliative care consultation (8.2% vs 12.0%, p=.02), be restrained (5.8% vs 11.6%, p<.001), have an order for nothing by mouth (50.1% vs 56.0%, p=.03), have a bladder catheter (31.7% vs 40.9%, p<.001), or die in the hospital (10.2% vs 15.47%, p=.004) and more likely to be discharged home (65.5% vs 58.2%, p=.01). CONCLUSION: Our study underscores the strong association between presence of a DNR order and mortality. Further studies are necessary to better understand the presence and timing of DNR orders in hospitalized older adults.

Dealing with death taboo: discussion of do-not-resuscitate directives with Chinese patients with noncancer life-limiting illnesses

DOI:10.1177/1049909119828116

URL

PMID:30744386

[Cited within: 3]

BACKGROUND: Noncancer patients with life-limiting diseases often receive more intensive level of care in their final days of life, with more cardiopulmonary resuscitation performed and less do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders in place. Nevertheless, death is still often a taboo across Chinese culture, and ethnic disparities could negatively affect DNR directives completion rates. OBJECTIVES: We aim to explore whether Chinese noncancer patients are willing to sign their own DNR directives in a palliative specialist clinic, under a multidisciplinary team approach. DESIGN: Retrospective chart review of all noncancer patients with life-limiting diseases referred to palliative specialist clinic at a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong over a 4-year period. RESULTS: Over the study period, a total of 566 noncancer patients were seen, 119 of them completed their own DNR directives. Patients had a mean age of 74.9. Top 3 diagnoses were chronic renal failure (37%), congestive heart failure (16%), and motor neuron disease (11%). Forty-two percent of patients signed their DNR directives at first clinic attendance. Most Chinese patients (76.5%) invited family caregivers at DNR decision-making, especially for female gender (84.4% vs 69.1%; P = .047) and older (age >75) age group (86.2% vs 66.7%; P = .012). Of the 40 deceased patients, median time from signed directives to death was 5 months. Vast majority (95%) had their DNR directives being honored. CONCLUSION: Health-care workers should be sensitive toward the cultural influence during advance care planning. Role of family for ethnic Chinese remains crucial and professionals should respect this family oriented decision-making.

Cultural differences in end-of-life care

DOI:10.1097/00003246-200102001-00010

URL

PMID:11228574

[Cited within: 1]

The exact time of death for many intensive care unit patients is increasingly preceded by an end-of-life decision. Such decisions are fraught with ethical, religious, moral, cultural, and legal difficulties. Key questions surrounding this issue include the difference between withholding and withdrawing, when to withhold/withdraw, who should be involved in the decision-making process, what are the relevant legal precedents, etc. Cultural variations in attitude to such issues are perhaps expected between continents, but key differences also exist on a more local basis, for example, among the countries of Europe. Physicians need to be aware of the potential cultural differences in the attitudes not only of their colleagues, but also of their patients and families. Open discussion of these issues and some change in our attitude toward life and death are needed to enable such patients to have a pain-free, dignified death.

Ethical and moral guidelines for the initiation, continuation, and withdrawal of intensive care. American College of Chest Physicians/ Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Panel

DOI:10.1378/chest.97.4.949 URL PMID:2182302 [Cited within: 1]

Death in emergency departments: a multicenter cross-sectional survey with analysis of withholding and withdrawing life support

DOI:10.1007/s00134-010-1800-1

URL

PMID:20229044

[Cited within: 1]

PURPOSE: To describe the characteristics of patients who die in emergency departments and the decisions to withhold or withdraw life support. METHODS: We undertook a 4-month prospective survey in 174 emergency departments in France and Belgium to describe patients who died and the decisions to limit life-support therapies. RESULTS: Of 2,512 patients enrolled, 92 (3.7%) were excluded prior to analysis because of missing data; 1,196 were men and 1,224 were women (mean age 77.3 +/- 15 years). Of patients, 1,970 (81.4%) had chronic underlying diseases, and 1,114 (46%) had a previous functional limitation. Principal acute presenting disorders were cardiovascular, neurological, and respiratory. Life-support therapy was initiated in 1,781 patients (73.6%). Palliative care was undertaken for 1,373 patients (56.7%). A decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments was taken for 1,907 patients (78.8%) and mostly concerned patients over 80 years old, with underlying metastatic cancer or previous functional limitation. Decisions were discussed with family or relatives in 58.4% of cases. The decision was made by a single ED physician in 379 cases (19.9%), and by at least two ED physicians in 1,528 cases (80.1%). CONCLUSIONS: Death occurring in emergency departments mainly concerned elderly patients with multiple chronic diseases and was frequently preceded by a decision to withdraw and/or withhold life-support therapies. Training of future ED physicians must be aimed at improving the level of care of dying patients, with particular emphasis on collegial decision-taking and institution of palliative care.

Why do general medical patients have a lengthy wait in the emergency department before admission?

DOI:10.1016/j.jfma.2012.08.005

URL

[Cited within: 2]

Background/Purpose: Emergency department (ED) overcrowding is a universal problem, especially with the shortage of hospital beds. We studied the characteristics and outcomes of patients with prolonged ED stays, which has rarely been studied before.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective study at a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. Prolonged stay in the ED was defined as a stay of more than 72 hours in the ED before admission. The medical records were reviewed for data analysis.

Results: From November 1, 2009 to January 31, 2010, a total of 1364 general medical patients were enrolled. The mean age was 66.4 +/- 17.8 years, with 53.4% male. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was 3.0 +/- 3.1. The mean length of ED stay was 43.9 +/- 41.0 hours. The CCI (4.1 +/- 3.5 vs. 2.8 +/- 3.0, p < 0.001) and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) rates (18.8% vs. 10.3%, p = 0.001) of the patients with prolonged ED stays were higher than those of the patients with shorter stays. For patients with high CCI (>= 3) and DNR consent, the odds ratio of prolonged ED stay was 1.73 and 1.60, respectively. Patients with prolonged ED stays also had a lower Barthel index (60.3 +/- 34.8 vs. 66.4, p = 0.011) and higher in-hospital mortality (11.6% vs. 6.0%, p = 0.006).

Conclusion: Complex comorbidities and terminal conditions with DNR consent were associated with the prolonged ED stay for general medical patients. The hospital manager should pay attention to general medical patients with multiple comorbidities as well as those who require palliative care. Copyright (C) 2012, Elsevier Taiwan LLC & Formosan Medical Association.

Prolonged length of stay in the emergency department in high-acuity patients at a Chinese tertiary hospital

DOI:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01588.x

URL

[Cited within: 1]

Objective ED overcrowding is a worldwide issue, with most evidence coming from developed countries. Until now, little was known about this subject in China. The aim of this study was to investigate the situation of prolonged lengths of stay (LOS) in the ED for high-acuity patients in a Chinese tertiary hospital and to identify associated factors. Methods A retrospective study was performed in a Chinese tertiary hospital from 1 January to 31 December 2010. The primary outcomes were ED LOS and associated factors in overall high-acuity patients. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used. Results In this consecutive study period, 7966 high-acuity patients presenting to the ED were triaged to the resuscitation room. The median LOS in the ED for these patients was 10.6?h (IQR, 3.123.1?h). In the multivariate analysis, the most significant factor associated with prolonged LOS was boarding for more than 2?h (OR, 4.29; 95% CI, 4.034.57). Patients requiring emergency operation or intensive care unit admission experienced a shorter LOS (OR, 0.56 and 0.76; 95% CI, 0.530.60 and 0.710.81, respectively). Older patients, night shift arrivals, non-spring visitors, general internal medicine patients and patients leaving without receiving advanced therapy had longer LOS. Conclusions We found an excessive LOS in the resuscitation room in this tertiary hospital. The most significant reason for prolonged LOS was boarding block. Shortage of inpatient beds and reluctance of the wards to admit these patients might be the primary reasons for extremely long boarding.

Documentation of code status and discussion of goals of care in gravely ill hospitalized patients

DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.03.035

URL

PMID:19327289

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Timely discussions about goals of care in critically ill patients have been shown to be important. METHODS: We conducted a retrospective chart review over 2 years (2003-2004) of patients admitted to our medical service who were classified as

Characteristics of patients who die in hospital with no attempt at resuscitation

DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.028

URL

PMID:15919565

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To describe the characteristics, cause of hospitalisation and symptoms prior to death in patients dying in hospital without resuscitation being started and the extent to which these decisions were documented. MATERIALS AND METHODS: All patients who died at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Goteborg, Sweden, in whom cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was not attempted during a period of one year. RESULTS: Among 674 patients, 71% suffered respiratory insufficiency, 43% were unconscious and 32% had congestive heart failure during the 24h before death. In the vast majority of patients, the diagnosis on admission to hospital was the same as the primary cause of death. The cause of death was life-threatening organ failure, including malignancy (44%), cerebral lesion (10%) and acute coronary syndrome (10%). The prior decision of 'do not attempt resuscitation' (DNAR) was documented in the medical notes in 82%. In the remaining 119 patients (18%), only 16 died unexpectedly. In all these 16 cases, it was regarded retrospectively as ethically justifiable not to start CPR. CONCLUSION: In patients who died at a Swedish University Hospital, we did not find a single case in which it was regarded as unethical not to start CPR. The patient group studied here had a poor prognosis due to a severe deterioration in their condition. To support this, we also found a high degree of documentation of DNAR. The low rate of CPR attempts after in-hospital cardiac arrest appears to be justified.

Hospital variation in utilization of life-sustaining treatments among patients with do-not-resuscitate orders

DOI:10.1111/1475-6773.12651

URL

PMID:28097649

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVE: To determine between-hospital variation in interventions provided to patients with do not resuscitate (DNR) orders. DATA SOURCES/SETTING: United States Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, California State Inpatient Database. STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study including hospitalized patients aged 40 and older with potential indications for invasive treatments: in-hospital cardiac arrest (indication for CPR), acute respiratory failure (mechanical ventilation), acute renal failure (hemodialysis), septic shock (central venous catheterization), and palliative care. Hierarchical logistic regression to determine associations of hospital

Bringing palliative care into geriatrics in a Chinese culture society—results of a collaborative model between palliative medicine and geriatrics unit in Hong Kong

DOI:10.1111/jgs.12760 URL PMID:24731031 [Cited within: 1]

Breaking bad news: a Chinese perspective

DOI:10.1191/0269216303pm751oa

URL

PMID:12822851

[Cited within: 1]

The amount of information received by terminal cancer patients about their illness varies across different countries. Many Chinese families object to telling the truth to the patient and doctors often follow the wish of the families. However, a population study in Hong Kong has shown that the majority wanted the information. To address this difference in attitudes, the ethical principles for and against disclosure are analysed, considering the views in Chinese philosophy, sociological studies and traditional Chinese medicine. It is argued that the Chinese views on autonomy and nonmaleficence do not justify non-disclosure of the truth. It is recommended that truth telling should depend on what the patient wants to know and is prepared to know, and not on what the family wants to disclose. The standard palliative care approach to breaking bad news should be adopted, but with modifications to address the 'family determination' and 'death as taboo' issues.

Determining resuscitation preferences of elderly inpatients: a review of the literature

URL

PMID:14557319

[Cited within: 1]

Studies have shown that discussions with elderly hospital patients about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) preferences occur infrequently and have variable content. Our objective was to identify themes in the existing literature that could be used to increase the frequency and improve the quality of such discussions. We found that patients and families are familiar with the concept of CPR but have limited understanding of the procedure and overestimate its benefit. Most patients are interested in being involved in discussions about CPR and in sharing responsibility for decisions with physicians; however, older patients who participate in these discussions may have variable decision-making capacity. Physicians do not routinely discuss CPR with older patients, and patients do not initiate such discussions. When discussions do occur, the information provided to patients or families about resuscitation and its outcomes is not always consistent. Physicians should initiate CPR discussions, consider patients' levels of understanding and decision-making capacity, share responsibility for decisions where appropriate and involve the family where possible. Documentation of discussions and patient preferences may help to minimize misunderstandings and increase the stability of the decision during subsequent admissions to hospital.

Epidemiology of advance directives in extended care facility patients presenting to the emergency department

DOI:10.5811/westjem.2015.8.25657

URL

PMID:26759640

[Cited within: 1]

INTRODUCTION: We conducted an epidemiologic evaluation of advance directives and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) prevalence among residents of extended care facilities (ECF) presenting to the emergency department (ED). METHODS: We performed a retrospective medical record review on ED patients originating from an ECF. Data were collected on age, sex, race, triage acuity, ED disposition, DNR status, power-of attorney (POA) status, and living will (LW) status. We generated descriptive statistics, and used logistic regression to evaluate predictors of DNR status. RESULTS: A total of 754 patients over 20 months met inclusion criteria; 533 (70.7%) were white, 351 (46.6%) were male, and the median age was 66 years (IQR 54-78). DNR orders were found in 124 (16.4%, 95% CI [13.9-19.1%]) patients. In univariate analysis, there was a significant difference in DNR by gender (10.5% female vs. 6.0% male with DNR, p=0.013), race (13.4% white vs. 3.1% non-white with DNR, p=0.005), and age (4.0% <65 years; 2.9% 65-74 years, p=0.101; 3.3% 75-84 years, p=0.001; 6.2% >84 years, p<0.001). Using multivariate logistic regression, we found that factors associated with DNR status were gender (OR 1.477, p=0.358, note interaction term), POA status (OR 6.612, p<0.001), LW (18.032, p<0.001), age (65-74 years OR 1.261, p=0.478; 75-84 years OR 1.737, p=0.091, >84 years OR 5.258, P<0.001), with interactions between POA and gender (OR 0.294, P=0.016) and between POA and LW (OR 0.227, p<0.005). Secondary analysis demonstrated that DNR orders were not significantly associated with death during admission (p=0.084). CONCLUSION: Age, gender, POA, and LW use are predictors of ECF patient DNR use. Further, DNR presence is not a predictor of death in the hospital.

Difficulty of the decision-making process in emergency departments for end-of-life patients

DOI:10.1111/jep.13229

URL

PMID:31287201

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: In emergency departments, for some patients, death is preceded by a decision of withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. This concerns mainly patients over 80, with many comorbidities. The decision-making process of these decisions in emergency departments has not been extensively studied, especially for noncommunicating patients. AIM: The purpose of this study is to describe the decision-making process of withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatments in emergency departments for noncommunicating patients and the outcome of said patients. DESIGN: We conducted a prospective multicenter study in three emergency departments of university hospitals from September 2015 to January 2017. RESULTS: We included 109 patients in the study. Fifty-eight (53.2%) patients were coming from nursing homes and 52 (47.7%) patients had dementia. Decisions of withholding life-sustaining treatment concerned 93 patients (85.3%) and were more frequent when a surrogate decision maker was present 61 (65.6%) versus seven (43.8%) patients. The most relevant factors that lead to these decisions were previous functional limitation (71.6%) and age (69.7%). Decision was taken by two physicians for 80 patients (73.4%). The nursing staff and general practitioner were, respectively, involved in 31 (28.4%) and two (1.8%) patients. A majority of the patients had no advance directives (89.9%), and the relatives were implicated in the decision-making process for 96 patients (88.1%). Death in emergency departments occurred for 47 patients (43.1%), and after 21 days, 84 patients (77.1 %) died. CONCLUSION: There is little anticipation in end-of-life decisions. Discussion with patients concerning their end-of-life wishes and the writing of advance directives, especially for patients with chronic diseases, must be encouraged early.

The attitudes of Chinese family caregivers of older people with dementia towards life sustaining treatments

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04230.x

URL

PMID:17474914

[Cited within: 1]

AIM: This paper is a report of a study to examine attitudes towards life-sustaining treatment in family caregivers of older Chinese people with dementia. BACKGROUND: Deferring decisions about life-sustaining treatments to surrogate decision-makers is common among older people with dementia. However, surrogate decision-makers frequently lack knowledge about disadvantages and benefits of treatments and do not understand the principles of surrogate decision-making. METHOD: A total of 51 Chinese family caregivers were interviewed during 2003 and 2004. The interview included an assessment of their knowledge about cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tube feeding, a questionnaire to assess their anticipated decisions for four treatments (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, artificial ventilation, tube feeding and antibiotic administration) if the older relative suffered critical illness or irreversible coma, and their comfort and certainty in making such decisions. FINDINGS: Family caregivers displayed poor knowledge about life-sustaining treatments, with 30 (59%) and 13 (26%) unable to name any feature of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and tube feeding, respectively. Most relied on their own views in decision-making rather than on what they thought their relative would have wanted. Most family caregivers were reluctant to forgo treatments. Nursing home residence predicted family caregivers' willingness to forgo artificial ventilation for critical illness. Financial burden predicted inclination to forgo antibiotics for critical illness and irreversible coma, as well as tube feeding in irreversible coma. CONCLUSION: More dialogue and education are needed about end of life issues in the early phase of dementia. Nurses should be aware of the cultural implications of surrogate decision-making for Chinese family caregivers.

Do-not-resuscitate status and observational comparative effectiveness research in patients with septic shock

DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000403

URL

PMID:24810532

[Cited within: 2]

OBJECTIVES: To assess the importance of including do-not-resuscitate status in critical care observational comparative effectiveness research. DESIGN: Retrospective analysis. SETTING: All California hospitals participating in the 2007 California State Inpatient Database, which provides do-not-resuscitate status within the first 24 hours of admission. PATIENTS: Septic shock present at admission. INTERVENTIONS: None. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS: We investigated the association of early do-not-resuscitate status with in-hospital mortality among patients with septic shock. We also examined the strength of confounding of do-not-resuscitate status on the association between activated protein C therapy and mortality, an association with conflicting results between observational and randomized studies. We identified 24,408 patients with septic shock; 19.6% had a do-not-resuscitate order. Compared with patients without a do-not-resuscitate order, those with a do-not-resuscitate order were significantly more likely to be older (75 +/- 14 vs 67 +/- 16 yr) and white (62% vs 53%), with more acute organ failures (1.44 +/- 1.15 vs 1.38 +/- 1.15), but fewer inpatient interventions (1.0 +/- 1.0 vs 1.4 +/- 1.1). Adding do-not-resuscitate status to a model with 47 covariates improved mortality discrimination (c-statistic, 0.73-0.76; p < 0.001). Addition of do-not-resuscitate status to a multivariable model assessing the association between activated protein C and mortality resulted in a 9% shift in the activated protein C effect estimate toward the null (odds ratio from 0.78 [95% CI, 0.62-0.99], p = 0.04, to 0.85 [0.67-1.08], p = 0.18). CONCLUSIONS: Among patients with septic shock, do-not-resuscitate status acts as a strong confounder that may inform past discrepancies between observational and randomized studies of activated protein C. Inclusion of early do-not-resuscitate status into more administrative databases may improve observational comparative effectiveness methodology.

Motives for self-referral to the emergency department: a systematic review of the literature

DOI:10.1186/s12913-016-1935-z

URL

PMID:27938366

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: In several western countries patients' use of Emergency Departments (EDs) is increasing. A substantial number of patients is self-referred, but does not need emergency care. In order to have more influence on unnecessary self-referral, it is essential to know why patients visit the ED without referral. The goal of this systematic review therefore is to explore what motivates self-referred patients in those countries to visit the ED. METHODS: Recommendations from the PRISMA were used to search and analyze the literature. The following databases; PUBMED, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Library, were systematically searched from inception up to the first of February 2015. The reference lists of the included articles were screened for additional relevant articles. All studies that reported on the motives of self-referred patients to visit an ED were selected. The reasons for self-referral were categorized into seven main themes: health concerns, expected investigations; convenience of the ED; lesser accessibility of primary care; no confidence in general practitioner/primary care; advice from others and financial considerations. A random-effects meta-analysis was performed. RESULTS: Thirty publications were identified from the literature studied. The most reported themes for self-referral were 'health concerns' and 'expected investigations': 36% (95% Confidence Interval 23-50%) and 35% (95% CI 20-51%) respectively. Financial considerations most often played a role in the United States with a reported percentage of 33% versus 4% in other countries (p < 0.001). CONCLUSIONS: Worldwide, the most important reasons to self-refer to an ED are health concerns and expected investigations. Financial considerations mainly play a role in the United States.

The worst is yet to come. Many elderly patients with chronic terminal illnesses will eventually die in the emergency department

DOI:10.1007/s00134-010-1803-y URL PMID:20229043 [Cited within: 1]

The experiences of emergency nurses in providing end-of-life care to patients in the emergency department

DOI:10.1016/j.aenj.2014.11.001

URL

PMID:25851917

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Managing death in the emergency department is a challenge. Emergency nurses are expected to provide care to numerous patient groups in an often fast-paced, life-saving environment. The purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of emergency nurses in providing end-of-life care, which is the care delivered to a patient during the time directly preceding death. METHOD: Data were collected from 25 emergency nurses during three focus group interviews. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using the qualitative techniques of grounded theory. RESULTS: Ten categories emerged from the data that described a social process for managing death in the emergency department. The categories were linked via the core category labelled 'dying in the emergency department is not ideal', which described how the emergency department was an inappropriate place for death to occur. To help manage the influence of the environment on end-of-life care, nurses reported strategies that included moving dying patients out of the emergency department and providing the best care that they could. CONCLUSION: The results of this study highlight nurses' belief that the emergency department was not an appropriate place for death to occur. Despite being frequently exposed to death and dying, the actions and attitudes of emergency nurses implied the need or desire to avoid death in the emergency department.

Do-not-resuscitate orders in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: the Worcester Heart Attack Study

DOI:10.1001/archinte.164.7.776

URL

PMID:15078648

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in Americans. Despite increased interest in end-of-life care, data regarding the use of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders in acutely ill cardiac patients remain extremely limited. The objectives of this study were to describe use of DNR orders, treatment approaches, and hospital outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. METHODS: The study sample consisted of 4621 residents hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction at all metropolitan Worcester, Mass, area hospitals in five 1-year periods from 1991 to 1999. RESULTS: Significant increases in the use of DNR orders were observed during the study decade (from 16% in 1991 to 25% in 1999). The elderly, women, and patients with previous diabetes mellitus or stroke were more likely to have DNR orders. Patients with DNR orders were significantly less likely to be treated with effective cardiac medications, even if the DNR order occurred late in the hospital stay. Less than 1% of patients were noted to have DNR orders before hospital admission. Patients with DNR orders were significantly more likely to die during hospitalization than patients without DNR orders (44% vs 5%). CONCLUSIONS: The results of this community-wide study suggest increased use of DNR orders in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction during the past decade. Use of certain cardiac therapies and hospital outcomes are different between patients with and without DNR orders. Further efforts are needed to characterize the use of DNR orders in patients with acute coronary disease.

Factors associated with combined do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders: a retrospective chart review at an urban tertiary care center

DOI:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.06.020

URL

PMID:29935341

[Cited within: 1]

BACKGROUND: In clinical practice, do-not-intubate (DNI) orders are generally accompanied by do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. Use of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders is associated with older patient age, more comorbid conditions, and the withholding of treatments outside of the cardiac arrest setting. Previous studies have not unpacked the factors independently associated with DNI orders. OBJECTIVE: To compare factors associated with combined DNR/DNI orders versus isolated DNR orders, as a means of elucidating factors associated with the addition of DNI orders. DESIGN: Retrospective chart review. SETTING/SUBJECTS: Patients who died on a General Medicine or MICU service (n=197) at an urban public hospital over a 2-year period. MEASUREMENTS: Logistic regression was used to identify demographic and medical data associated with code status. RESULTS: Compared with DNR orders alone, DNR/DNI orders were associated with a higher median Charlson Comorbidity Index (odds ratio [OR] 1.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13-1.43); older age (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01-1.04); malignancy (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.18-4.37); and female sex (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.02-3.87). In the last 3 days of life, they were associated with morphine administration (OR 2.76, 95% CI 1.43-5.33); and negatively associated with use of vasopressors/inotropes (OR 10.99, 95% CI 4.83-25.00). CONCLUSIONS: Compared with DNR orders alone, combined DNR/DNI orders are more strongly associated with many of the same factors that have been linked to DNR orders. Awareness of the extent to which the two directives may be conflated during code status discussions is needed to promote patient-centered application of these interventions.